“Mom. You’ve been eating dinners standing over the kitchen sink for weeks now. Enough.”

“Mom. You’ve been eating dinners standing over the kitchen sink for weeks now. Enough.”

From the far wall, the life-sized portrait of my daughter, who has been dead over three years, smirks at me. I turn away to rinse the tiny Stone Wave pot I store food, cook and eat from. But I still hear Marika’s words, “Mom, you’re becoming a hermit.”

“Yeah, but I’m on this weird diet that makes it impossible to eat out. All my friends are away this week anyway. And everyone else is coupled-off now so … Besides, I have a lot of work to do,” I say.

“Mom.” With this one word she can still shut me up, like gunshot.

A year after my daughter died, family and friends were sending mixed messages: get over it, it’s time to let go; take as much time as you need to heal; you will never get over this.

In support groups I watched bereaved parents tell their stories and grasp for tissues with quivering hands. Grief was not something to get over or through, the counselors told us. They said grief was a measure of love so I imagined love as a long ribbon with grief and joy at opposite ends. The evening a mother announced she still talked to her dead son, I felt I’d joined the right club. That’s when I knew my daughter would be with me, in some way or other, forever.

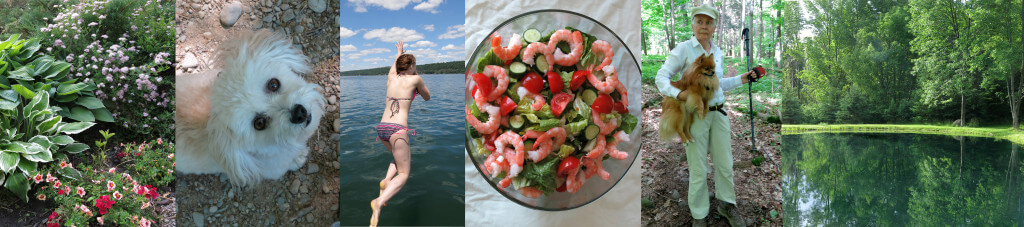

I decided to make it a good thing. Marika could be a positive force in my life; I’d hang onto her but allow her memory to pull me up and out into the world she loved. It meant I’d have to live bigger in order to live for us both.

That is how I came to be at Ithaca’s Istanbul Turkish Kitchen last week, seated at a table piled with beautiful food, with nine new and old friends, and eight bottles of wine.

We are ALL dying. This is what I tell myself, driving to the hospice center to train to be a morning-shift kitchen volunteer. Even with weeks of hospice training, I’m still nervous about interacting with people who are dying. I don’t want them to see behind my eyes, the hidden thought: you might not be here when I return next week. So I keep telling myself we’re All leaving town sooner or later – some of us just have an earlier flight.

We are ALL dying. This is what I tell myself, driving to the hospice center to train to be a morning-shift kitchen volunteer. Even with weeks of hospice training, I’m still nervous about interacting with people who are dying. I don’t want them to see behind my eyes, the hidden thought: you might not be here when I return next week. So I keep telling myself we’re All leaving town sooner or later – some of us just have an earlier flight. “Thank you, Dad,” I say to my father almost every day.

“Thank you, Dad,” I say to my father almost every day. I don’t curse. Probably because of all the hours I spent as a kid in the back of my mother’s car, stuck in traffic on the Long Island Expressway, with my mother ranting at the wheel. There were f—ing idiots driving alongside us, damn a–holes in front of us, and stinkin’ s—heads in the front. The swearing fascinated me. I couldn’t master her competence or style. So I never tried.

I don’t curse. Probably because of all the hours I spent as a kid in the back of my mother’s car, stuck in traffic on the Long Island Expressway, with my mother ranting at the wheel. There were f—ing idiots driving alongside us, damn a–holes in front of us, and stinkin’ s—heads in the front. The swearing fascinated me. I couldn’t master her competence or style. So I never tried.