I was ashamed to admit I still talk to my daughter who died. And I was afraid that if I let go of her, or allowed my grief to dissipate even an ounce, we would both be lost. Other than that, seven years out from Marika’s death, I thought I’d figured out this thing called grieving, and was finally, kinda pretty-much (most days) at peace with the way things had turned out. I was okay, except for hanging onto her and feeling like maybe I was defective because I wouldn’t let myself detach.

I was ashamed to admit I still talk to my daughter who died. And I was afraid that if I let go of her, or allowed my grief to dissipate even an ounce, we would both be lost. Other than that, seven years out from Marika’s death, I thought I’d figured out this thing called grieving, and was finally, kinda pretty-much (most days) at peace with the way things had turned out. I was okay, except for hanging onto her and feeling like maybe I was defective because I wouldn’t let myself detach.

Then, last week, I learned about continuing bonds, a modern view of grief where therapists encourage preserving but redefining the relationship one has with a loved one who died. Even altered by the absence of the physical presence, connections with the deceased can still grow and continue for the lifetime of the one left behind. The continuing bonds theory contends that staying connected, rather than ending the relationship, helps the bereaved cope with loss and the ensuing changes in one’s life.

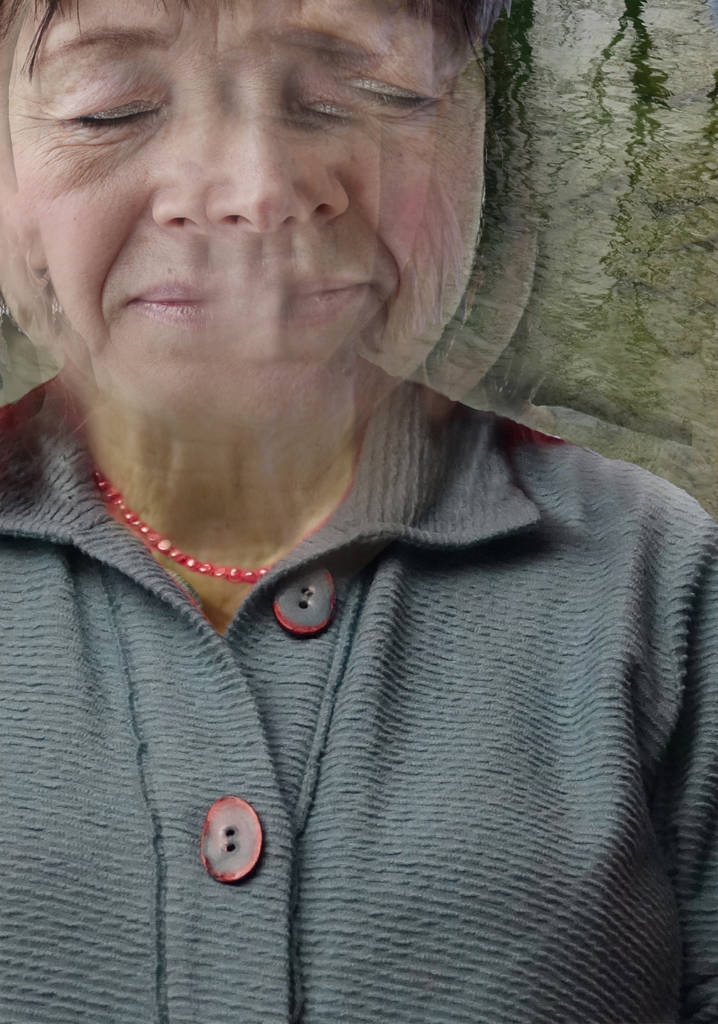

For years, to feel closer to Marika, I’ve been talking to her, letting her inspire and guide me, taking up some of the things she did, learning to love what she loved, wearing her scarves and tight jeans, and eating sushi every chance I get. She was a writer and blogger so I became a writer and blogger. She loved Facebook and photography. So…. This was the only way I could survive.

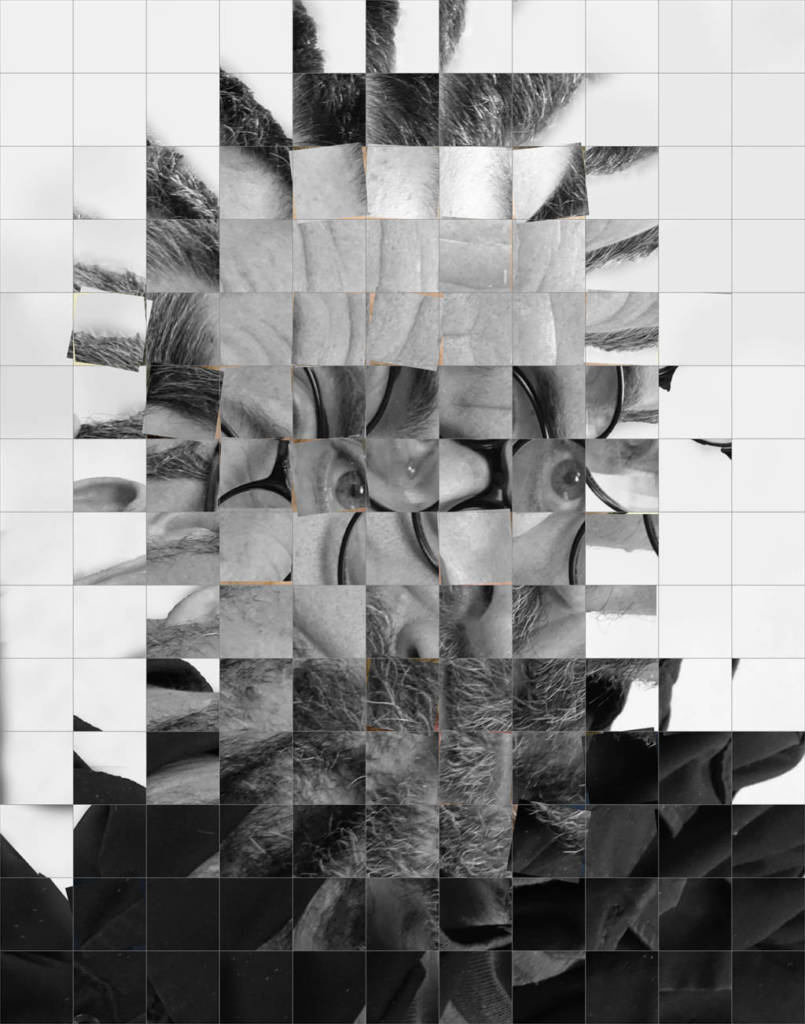

This week’s assignment in photography class was to turn the camera on our-selves to make conceptual self-portraits, ones that express some facet of personal identity. I answered the same questions I pose to my other subjects: What is it like to do what you do? What did you lose? What did you find?

What it’s like to keep on loving Marika’s ghost – It’s comforting. It’s like I’m carrying her, like I did before she was born. Like I always have her close by my side. It makes me stronger. Braver.

I lost the feeling that I had to hide my ongoing attachment to my daughter. I found that our once rocky relationship has matured and mellowed over the past seven years. Marika used to say, “Mom, you’re a wimp.” And now I hear, “Mom, you can do this.”

How do you cope with loss and the accompanying changes in your life? In what other ways can one stay connected to a loved one who died?