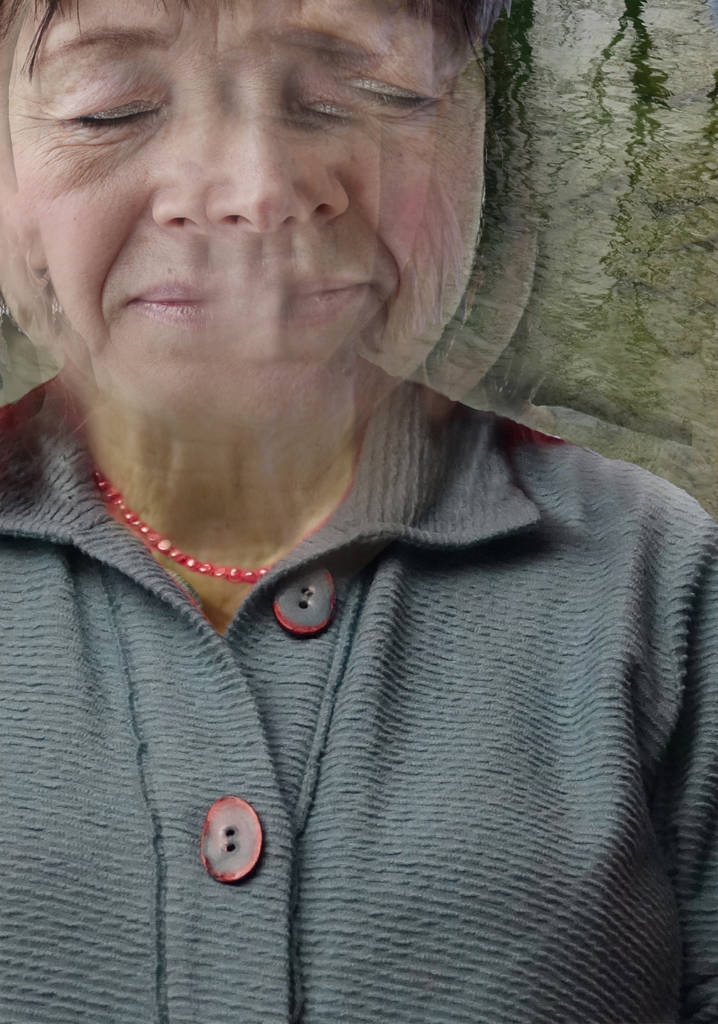

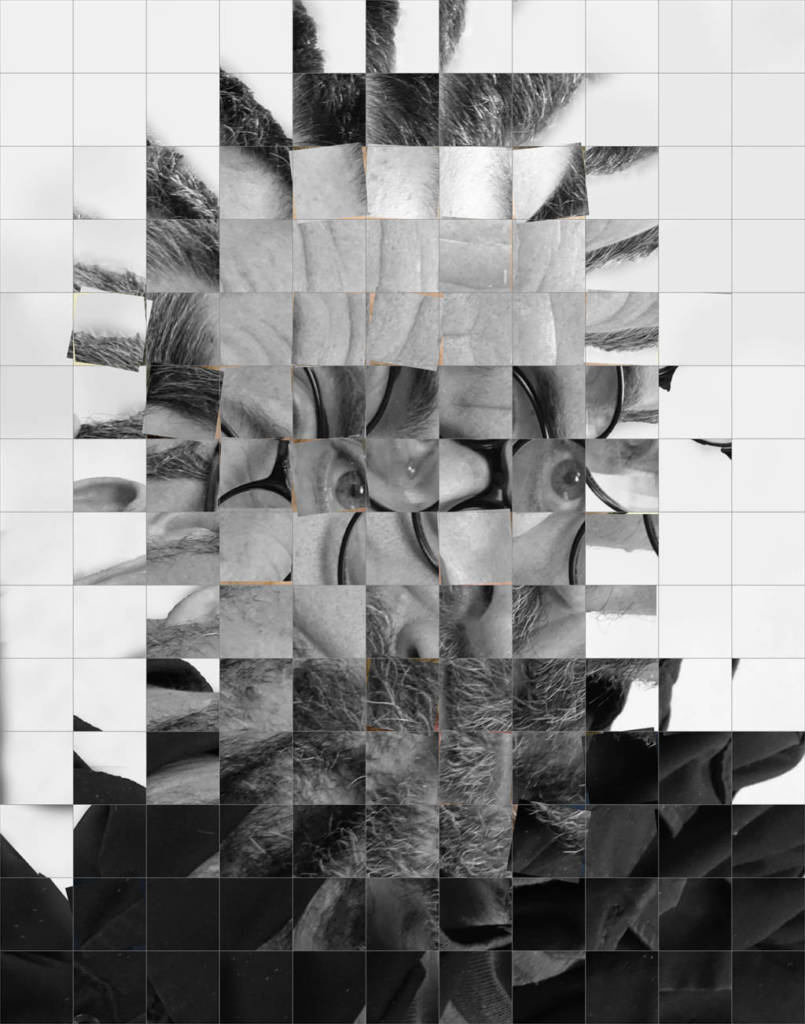

This is my portrait of – let’s call him Working Hard. W.H. for short. He admits he’s a workaholic. Proud of and dedicated to his calling as a paramedic, W.H. would probably not be impressed by this quirky style I chose to experiment with for his portrait. Inspired by the works of artist/photographer Chuck Close, I, myself, worked hard turning my original photo of W.H. into a grid, and then twisting the individual squares to demolish his identity.

This is my portrait of – let’s call him Working Hard. W.H. for short. He admits he’s a workaholic. Proud of and dedicated to his calling as a paramedic, W.H. would probably not be impressed by this quirky style I chose to experiment with for his portrait. Inspired by the works of artist/photographer Chuck Close, I, myself, worked hard turning my original photo of W.H. into a grid, and then twisting the individual squares to demolish his identity.

W.H. deserves to have his image treated with a lot more respect. He should be portrayed with monumental dignity. After all, he saves lives. As opposed to me. I gave birth twice, but miscarried twice, aborted two lives, and pulled the plug on one life. Not to mention the countless pets I’ve put down over the years. I don’t think I ever saved a life.

Years ago, I tried to keep up with a speeding ambulance as it rushed my daughter from a hospital in Ithaca to one in Rochester. She almost died on the way. But the EMTs saved her. So, I’m in awe of EMTs and paramedics. Touring a nearby fire station last week, I literally jumped at the invitation to enter their ambulance. It was my first time inside one.

“What’s it like to save a life?” I asked W.H., as I examined every inch of the neatly accommodated van with its medical supplies secured behind straps and doors.

“Sobering,” he replied, “It’s a large responsibility to shoulder. We cannot predict when something life-threatening happens. When we do save a life, it’s a moving experience.”

“What did you lose and what did you find?” I asked. He struggled with this.

“What I didn’t lose was my compassion,” he finally said. “It’s very easy in emergency medicine to become hardened to the circumstances of the people around you…. Emergency medicine tends to lead practitioners to feel that people are essentially suffering from their own bad decisions, driving drunk, smoking … but I have not lost my sense of compassion.”

He’d said, “Sobering,” about saving a life. “A moving experience.” I wanted to hear something more like Soaring. Something related to glory, jubilance, elation, and ecstasy. Because “sobering” is kind of what I felt watching my beautiful girl take her last breath. And compassion? That’s what I eventually found, after becoming a mother who could not save her daughter’s life, when I discovered too many others experiencing the same sorry thing.

I’m grateful to W.H. and all practitioners in Emergency Medical Services, for working to save lives. It can’t be easy, straddling the cusp between life and death.

What did you find and what did you lose in your life? Who or what saved you? Who or what did you save?

Please Share on your Social Media