“We have a donor for you,” the Roc Docs announced at our meeting, like they were giving Marika a birthday gift. “He is twenty-nine years old.” Age and gender was all the information the transplant team could share about our donor.

“The transplant preparations take two weeks, and the donor is available in mid-November.” Because of her history of extreme reactions to treatments, Marika would have to stay in the hospital during the rigorous preparations. “So you’ll be admitted at the end of next week,” they said. Startled by the short notice, I must have gulped. Suddenly seven sets of eyes turned to me. Then a small voice popped up, not my own.

“I can’t,” Marika said, and the focus honed in on her. “My concert. I have to do my concert.” There was a stunned silence in the small, overstuffed room.

“Your concert? But—um, when is your concert?” one of the team finally asked.

“It’s either the 26th or 27th of November. We’re still working out the details.”

“Uh, we can see if the donor can wait,” one of the team suggested uncertainly. Leftover smiles were frozen on the faces of the doctor, the social workers, and the nurses. They eyed each other in disbelief. Then they looked at me like I should do something. I heard myself swallow. No one said to us, “We’re worried about losing our small window of opportunity” or “We might lose our donor.” If this was a bad idea, it wasn’t being made clear. They simply nodded and said they would ask the donor if he could be available at another time. So everything was put on hold. My stomach was grinding bricks.

“Are you out of your mind?” Bewildered when I told her, Laurie yelled at me over the landline back home. “Remission doesn’t wait around for you to check everything off your to-do list.” She said nothing to Marika, didn’t yell at her. But a day later, she called back to ask me, “So, what’s the new game plan?”

“The concert is on Friday, November 26th. We get admitted on Monday the 29th, and the transplant is on Monday, December 6th. Wanna come out for Thanksgiving?”

“No, but I wouldn’t miss that concert for the world,” she promised.

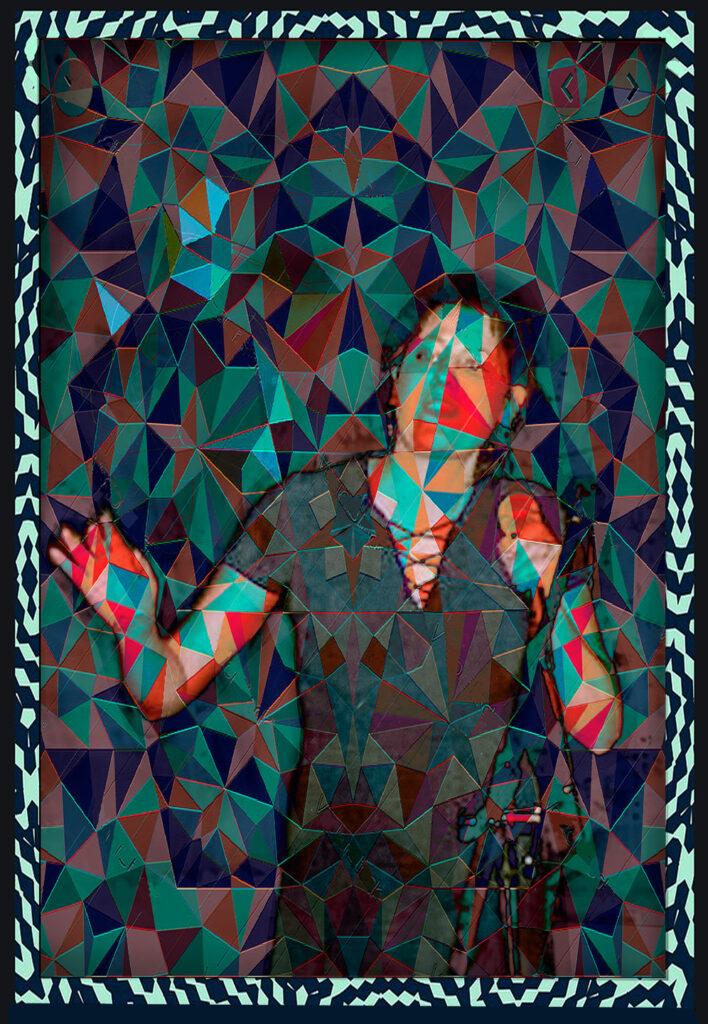

Thanksgiving in Ithaca is a chaotic coming and going of thousands. Evacuating students, mostly. But also friends and neighbors. The people you count on to participate in putting on a concert, or to show up. All the movement over the course of a few days makes planning an event during this time period an exercise in patience, creativity, and faith. Marika and Russ scrambled about to get a back-up singer and other musicians from people who had not yet heard their music. By the day after Thanksgiving, the night of the concert, The Nines in Collegetown was packed. I knew almost everyone there, and their mothers. Saving a seat for Laurie, I nursed a beer at a table with friends as we ate pizzas and tried to hear ourselves talk over the clamor of The Nines, known for its crowds, Blue Monday jams, and deep-dish pizzas. Our excitement and anticipation were at a peak when simultaneously, the band appeared and Laurie arrived. My eyes immediately zoned into an examination of Marika. Cute dress. When did she get that? She’s wearing the boots I gave her. She looks happy. She looks tired, like she just woke up.

Pleased with the crowd, Marika started singing “Party Jam,” a short song she and Russ wrote. Her large earrings dangled wildly as she moved to the music. In the back, Russ beat away at his drums. I was mesmerized watching my daughter doing what she dreamed about. I ordered another beer.

“Hello everyone. Welcome to the Nines,” Marika said cheerily, and went right into “Soldier,” a song she had written for her brother who was there in the crowd, recently honorably discharged from the army. She grimaced at her back-up singer who, unfamiliar with the tune, sang off key. The singer wore an old ridged washboard tied around her neck, which she struck with two drumsticks. I glanced across the room at her mother who smiled proudly at her healthy, spirited daughter.

“Don’t forget to tip those bartenders,” Marika ordered at the end of the song. “I wanna see more of you dancin’,” she yelled. The crowd cheered. The music got louder, and she danced. Then we all danced. We bumped into each other and laughed, waving our arms. It didn’t matter that we could hardly hear the songs over the percussion. This was what we’d waited for, what our lives had been put on hold for. The crowd at the Nines was crazy. The music boomed and Marika was in command. I wanted to freeze-frame the moment. She sang “Never After” and trailed off, “I am not going anywhere, I am not going anywhere, I am not going anywhere.”

Finally, with a victorious smile, finger pointing and fist punching the air, Marika shouted a song by Cake, “I want a girl with a short skirt and a lo-o-ong jacket.” A raucous finale. Just in case anyone was thinking this concert was to be her swan song. Sometimes I wonder if Marika knew it would be her last performance.

It was ending. Please don’t let it end, don’t let it be over yet, I pleaded in my head, sending a grateful prayer to whatever kind spirit might be watching my world. Cheers to Russ and all the musicians, to all the servers at The Nines, to everyone in the crowd. I shot blessings to the doctors who waited and the donor who waited.

Laurie and I walked back to the car, our Frye boots scuffing the sidewalks of late-night Collegetown. My ears still rang. In the dark streets, the dazzling streetlights were kaleidoscoped by my tears.