My daughter was measured and marked for radiation. In a waiting area down the hall, I chewed at my cuticles as Marika got the first of her full body radiation treatments. She had to be seared and zapped cell by cell in order to live. It made me nauseous. They wheeled her back to the room on a gurney and she napped the rest of the day as I sat, waiting in the dimmed light by her bedside. At dinnertime neither of us could eat. I gently rubbed her feet before driving off to Hope Lodge.

At Hope Lodge on Tuesdays I got free massages. Thursdays it was free dinners prepared by a group of med students. I took Bernadette, a cancer patient who lived there, out for port on her birthday, and watched another resident cook aromatic African dishes. In the afternoons I explored Swan’s German Market, the Public Market, the Monroe County Library, and Captain Jim’s Seafood, always bringing back some bit of Rochester for Marika. Each day I exhausted myself into oblivion. And then the transplant preparations got stepped up.

“Preparations,” Laurie said over the cell phone, “is really a euphemism here. What it really means is wiping out her blood cells and immune system with chemotherapy and radiation, and then ‘rescuing’ her with the donor’s cells.”

“Laur, what’s the deal with GVHD?”

“Didn’t you read any of the stuff I sent you?”

“I did, but it sounds better coming from you,” I said.

“Well, Graft Versus Host Disease is a fascinating condition. What can happen, just about any time in the first year or two after the transplant, is that the immune cells in the donor marrow can begin to attack the recipient’s tissues and organs. They still think they have to protect against ‘foreign invaders,’ and are totally clueless that THEY are the foreigners.”

“Yeah, they warned us it could get nasty,” I said, wincing.

“It’s her only shot, though. There are no more drugs capable of giving her a cure,” Laurie said. I knew that. I was still stuck on the part about the donor’s cells attacking tissues and organs “any time in the first year or two.”

It was snowing on transplant day, January 26, 2011. All morning long I watched outside the hospital window and checked online for weather-related transportation delays. Finally, midday, a courier delivered the stem cells in a picnic cooler. I collapsed on the end of the bed. Giddy with relief, I even smiled and joked with my ex-husband who had arrived with his wife and a cake. We gathered around to watch the donor’s blood product slowly seep into Marika’s veins via a long tube in which I pictured tiny cells charging forward on teensy running feet with swords pointing ahead. We had a little birthday party, and toasted to Marika’s new life, with Martinelli’s bubbly apple cider. After, in a trance, I washed my hands in the non-patient bathroom down the hall by the elevators, and sang softly, “Happy birthday to you, happy birthday to you. Happy birthday,” I choked, “dear Marika.” My eyes filled. My jaw quivered, “Happy birthday.” It was like whispering a prayer. Only I was downright pleading for my daughter’s recovery, “To you.”

The next morning, I returned early to the hospital from Hope Lodge. Marika sat in bed peering down at her chest, her head angled to accommodate her good eye. She was flushing out and disinfecting her own port as a nurse gave directions. Glancing up at me, Marika smiled. She looked ready to take on the world. Like she could deal with aggressive foreign cells, or doctors who dared to tell her No, or whatever else life might throw at her.

“Mom. I just got accepted into the University of Technology Nursing Program. I’m going to Australia next year.”

Two weeks later, on a Friday afternoon in early February, she was pedaling away on an exercise bike someone had left in her room. In sweat pants and a tee shirt, she almost looked like her old self, the athlete, the soccer player, the powerhouse-Marika who would sneer at my panting as we jogged around the block together.

The car was packed for my trip home for the weekend. I felt torn, as I always did, whenever I left Strong.

“Don’t forget to put your laundry in the new blue laundry bag,” I reminded her.

“O-Kay, mom,” she said, dismissing me.

“And remember to keep yourself hydrated. No caffeine drinks.”

“Mom, okay.” She rolled her eyes.

“And when’re you gonna take these pills that have been sitting here all morning?”

“Mom! Get a life,” she barked. “Go.” Conscious of my nagging, I silently picked up my computer and the old green bag of dirty laundry. I walked out the door. Without a look back.

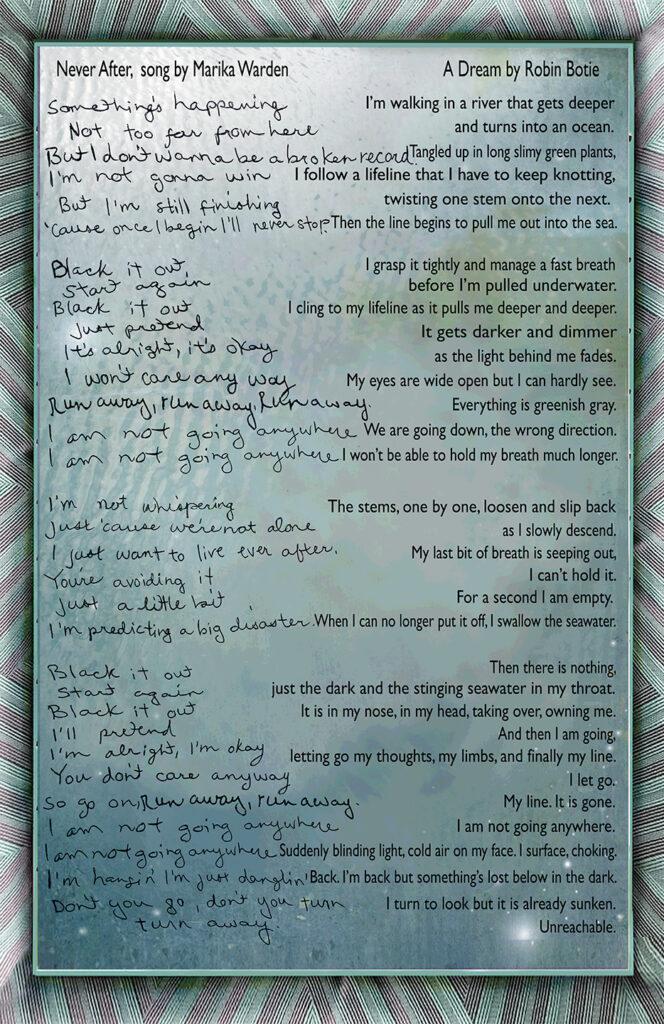

Late that night I got a call. Marika had been admitted to the Intensive Care Unit with pneumonia, low blood pressure, and respiratory failure. She’d asked for me as it became more and more difficult to breathe, while her doctors and nurses awaited her consent to be sedated and intubated. Somehow, at home, before racing back to the hospital early the next morning, I slept. I know, because I wrote down my dream.