It is the day before my first Christmas Eve without Marika. No Christmas this year. No Chanukah. Holidays seem pointless without Marika. So I’m erasing the whole season. Instead I’ll clean and write and do un-holiday-type things. Like clearing out the last of Marika’s belongings.

It is the day before my first Christmas Eve without Marika. No Christmas this year. No Chanukah. Holidays seem pointless without Marika. So I’m erasing the whole season. Instead I’ll clean and write and do un-holiday-type things. Like clearing out the last of Marika’s belongings.

I had surprised myself, and others, by how quickly I got rid of her things. It had been eerily easy. Somewhere, someone said cleaning up after a dead loved one is an important aspect of achieving closure. Closure—hah! Not for me. It is more like a desperate urge to re-home the many pieces of Marika. I am seeding the world with her stuff. It requires a great trust in the universe to find the right new person or place for the pretty prom dresses, the high-heeled shoes, stuffed animals … and now, the old desktop computer in her room. Marika hadn’t used it since shortly after she got cancer, after my father gave her a new laptop for college. Staples will recycle the old computer for ten dollars.

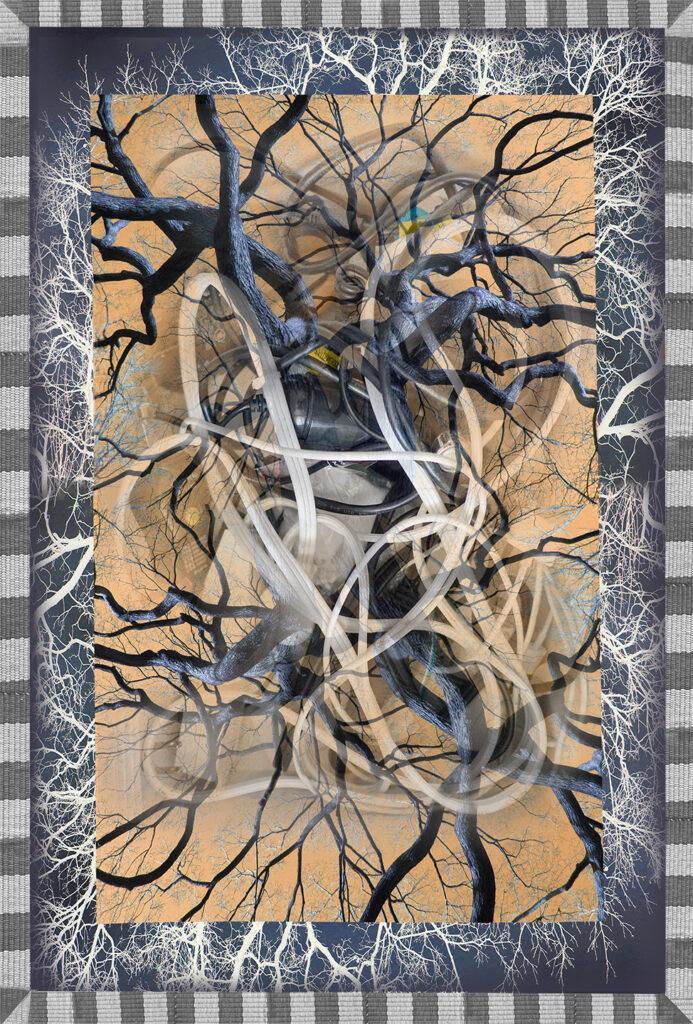

Rachel comes over to help me get it into the car. It feels less intrusive to rummage through Marika’s underwear drawer or her journals than to go anywhere near her old computer. But we briefly check it for anything I might want to keep. Nothing. I crave the writings of the almost-adult Marika, but this computer predates that. So Rachel tears it from the tangled mass of cables and wires, the arteries and veins that bind it to home.

“I ended up drunk in the ER every weekend. It was like I was suicidal,” Rachel tells me as she pulls cords out from under the desk. I keep my mouth shut. “When I went into Rehab, I was out of contact with the world for twenty-eight days. No phone, no computer,” she says.

“Are you back at work now? What was that last job? Working as a caseworker?”

“Yeah. I had to resign when I went to Rehab. I loved that job.”

“That was a neat job,” I say. She carries the computer down the stairs and I follow.

“Can you read some of the book to me?” she asks, after she shoves the computer into the car. She reminds me of Marika as a young child begging me to read. But before I can begin, Rachel’s cell phone rings. She listens briefly.

“What are you doing in a bar, you goofball? Get out of there. Fast,” she says. Then, “You’re gonna throw sixty days of sobriety down the trash for a girl?” As she speaks to this person in crisis, I am awed at how together Rachel sounds. She seems to have found herself after this difficult year of loss, substance abuse, and Rehab. Her head is in a good place, whereas I feel lost. After the last three sad but blessed years of knowing exactly why I was where I was, I now find myself directionless.

Later, alone in the Staples parking lot, I can barely lift the computer tower out of the car and into a shopping cart. I know I’m in trouble when, wheeling the loaded cart through the automatic doors, I have a flashback to last year at this time when I pushed Marika in a wheelchair through similar doors at the hospital. But soon, two Staples technicians are operating with screwdrivers and pliers to pull the ancient computer apart. The younger tech, about Marika’s age, extracts and then hands me the hard drive, a small but surprisingly heavy black metal box. It says “Fragile” on it and contains all her old high school homework, snippets of printed conversations with friends, playlists, … young girl-stuff locked up inside. It is like holding Marika’s heart. The technician draws stars in blue ink on the white label.

“Drill here. When you get rid of a computer you have to destroy the hard drive,” he says. Too mesmerized by the mysterious box in my hands, I don’t question why Staples doesn’t just take it and complete the job themselves. Through sobs, I ask the tech whom to pay the ten dollars to, and he tells me there’s no charge. On the verge of a major meltdown, I take Marika’s Heart Drive and flee.

My son, on his way out just as I arrive home with the somber little black box, offers to blast it apart at his next shooting session. Remembering how proud Marika had been of her brother shooting a shotgun off the deck during one of her parties, I give it to Greg. After all, maybe he needs some closure.