It was all distractions. Diversions. Detoured from our former daily missions, we’d do anything to pass time so we could just go home again, live our real lives, and be normal.

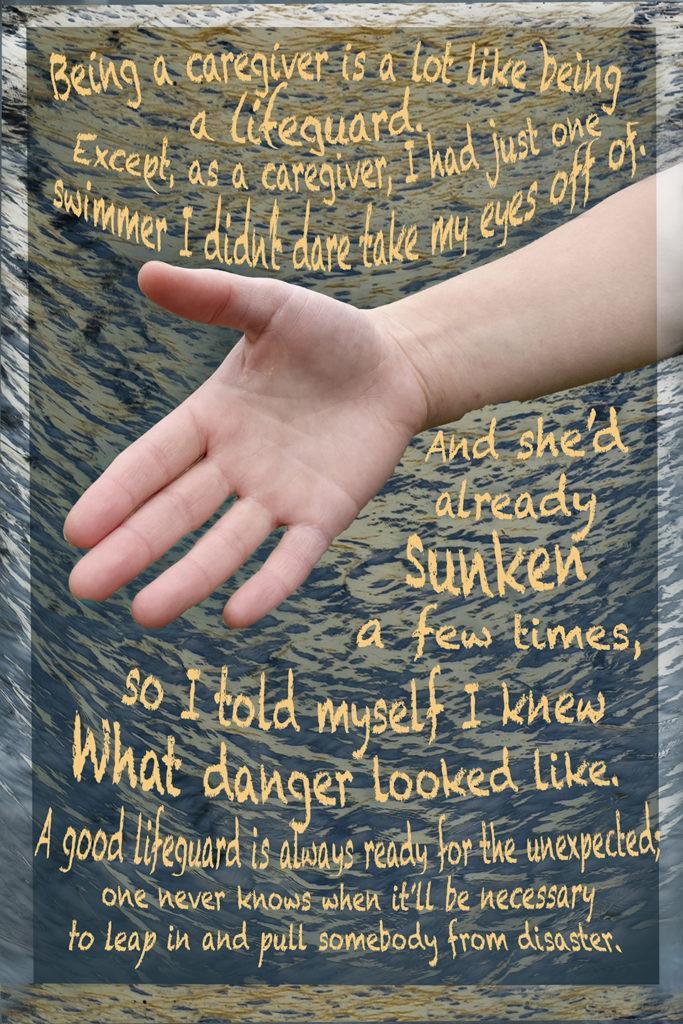

I discovered I liked being a caregiver. I also learned that my toughest challenges always seemed to involve the invisible. Like germs. Fungi, bacteria, and viruses surrounded us. My days revolved around avoiding them. Water bottles and food older than a day were thrown out. It was comforting to wash my hands in very hot water, humming the Happy Birthday song twice, the recommended amount of time to eliminate germs. And I loved “Purelling,” using hand sanitizer, forty times a day. But despite my phobic efforts, Marika was always being plagued by something I couldn’t see. Like abnormal blood counts. We waited every morning for the daily report. If the numbers were right, she could leave the room with a mask on, eat an apple, visit nurses on other units, maybe even go home. I couldn’t see it in her face or her demeanor. She could be feeling terrific but if the counts weren’t where they should be, we weren’t going anywhere.

And I, myself, was invisible. Afraid of being told to go, either by Marika or her doctors, I made myself small. I was the fairy facilitator, barely noticed until clean clothes, food, or a hand to squeeze during a shot was needed. Much of the time Marika pretended I was not there. But I knew that she knew I would always be there for her. The hard part was my invisibility when dealing with the rest of the world. Like her father. I’d report to him daily after the morning rounds, and immediately when there was trouble. But he’d call the nurses and doctors anyway, so I felt overlooked. Invisible. And Laurie. She emailed online newsletters to keep family and friends posted so they could support Marika.

“Laur, what about me? You report the news like you’re the one stuck here in the trenches getting all the information yourself. There’s never any mention of me or my efforts,” I cried, like a jealous four-year-old with a new baby in the family. The doctors stopped addressing me. The nurses, many only a few years older than Marika, were devoted to her and visited often. From my lonely corner by the recycling buckets and hazardous waste containers, I peeked at the company that came and went. “I’m her mother,” I wanted to scream. “She wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for me.” No, she wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for cancer, I corrected myself. And in my heart I was grateful for the attention Marika got. I might be small and insignificant, but not to her.

“Mom, can you get me some Pacifica Brazilian Mango perfume at Wegmans?” she pleaded, with a silly pout. Then I was practically skipping out the door.

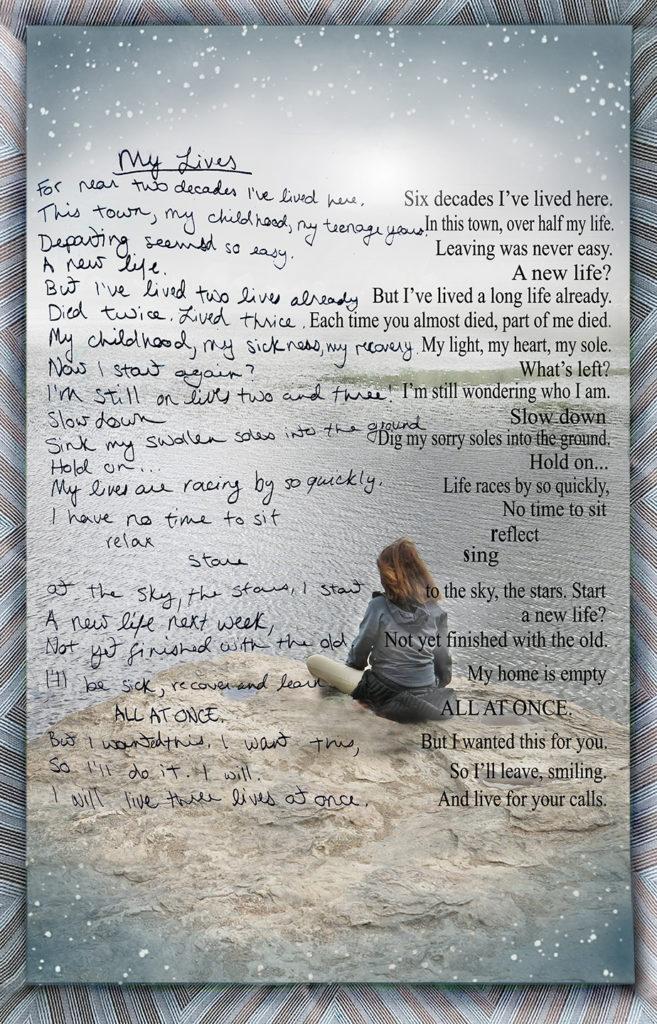

July. August. There was so much hope. We charged up and down the hallways dragging the IV stand by its cord, taking turns pushing the wheelchair, both of us wearing masks to ward off germs. Wending our way around meal carts, we dared the despicable germs to try to catch us. Marika had already recovered from major episodes of seizures, pneumonia, septic shock, and respiratory failure. Twice she’d emerged smiling victoriously from complete life support in the ICU. She was a star, on life number three, and we couldn’t imagine that she wouldn’t always be able to produce a miracle. Stunned and proud, and tethered behind like a small dumb dinghy, I sailed, always in her wake.

The gall bladder surgery took three hours. I sat alone in the hallway chewing my cuticles until it was over. There were complications. She came through but would need more recovery time. This would set back the final chemo treatment and thereby create a major timing crisis. The chemo required two weeks of careful monitoring as her cell counts were put into crash mode. But freshman orientation was coming up fast.

“She can’t miss orientation,” Laurie pleaded over the phone, “That’s when students learn how to make college work for them and how to go about screwing it up. Lifetime friendships are formed during that first week. It’s critically important.” I remembered my own college orientation, the excitement of beginning the new adventure that was mine alone, not my family’s. That was what I wanted for my daughter. But I kept quiet and let her work with Laurie to devise a plan the doctors would accept.

Early on a crisp morning at the end of August I drove Marika from home to Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. I helped her unpack. Laurie joined us, elated that Marika was finally going to live close by. It was a magical day, sunny and warm, full of excited students and other apprehensive parents.

“Do you believe we made it?” I said, over and over, drunk with happiness as we inspected the dorm, its bathrooms and community spaces. Laurie and I followed Marika to the registrar, the computer center, the dining hall, and finally the health center where we made sure they were well aware of what Laurie affectionately termed “the little time bomb” they now had in their midst.

I cried all the way back to Ithaca. Our scrimmage with cancer was over. It had ended well. Marika would get her college orientation and the first week of classes, I reminded myself. She would stay with Laurie in a hotel between the school and the medical center during the riskiest days. And in two weeks she’d return home, briefly, for her third round of chemo at Strong. I would go with her to Rochester until her counts allowed her to recoup at home. And then she’d be off to the university again. It was a good plan; everyone was satisfied.

So she’d been launched. Her new life was beginning. Marika belonged to Massachusetts and Clark University now, six hours from home. She belonged to Laurie. She belonged to the Greater World at last.

Mission accomplished.

There was plenty to worry about.