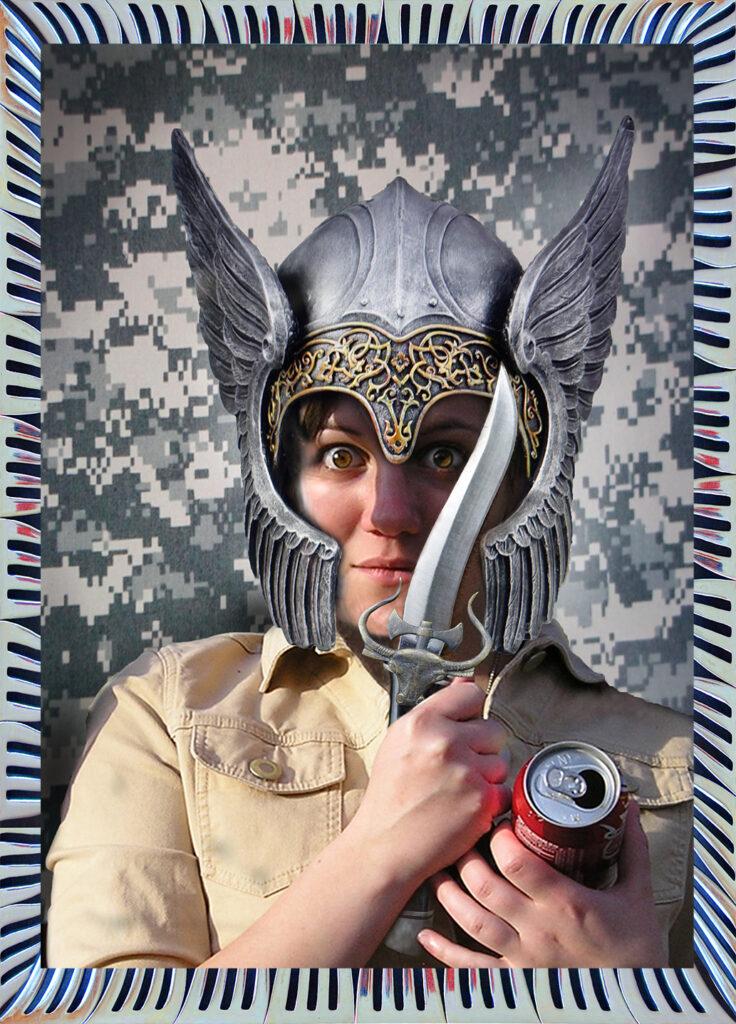

For my holiday gift I’d asked my son for a shooting lesson. So on the unseasonably warm afternoon of Christmas Eve 2011, Greg comes downstairs with two long guns. Trembling, I wrap up in scarves, earplugs, earmuffs and hooded jacket, and follow him out the door and across the lawn. He stops just short of the pond, props his shotgun against a tree, and hands me the rifle. Remington.22, he tells me. And then he shows me how to hold, load, and ready it for shooting.

“You don’t pull the trigger,” he says, “you squeeze it. You hug it with your whole hand.” Willing my eyes to stay open, I squeeze and shoot. It’s not nearly as loud or as jarring as I’d expected. Marika would have said, “LikeBAM!” Hardly drawing a breath, I shoot again. Bam! The sky echoes with each ferocious bark. Handling this loaded rifle, cradling it so close, and then blasting the air—LikeBAM! —I am spellbound, conscious only of being just on the cusp of control or calamity.

We had placed two targets against a large willow tree across the pond. The targets were a gift I’d painted for Greg. The one I’m to use is a cartoon image of a rotund woodchuck with a bulls-eye bellybutton. We train the scope, first focusing far, and then zooming in so every breath and movement I make is exaggerated in the scope, and the woodchuck bounces in a dizzying scene. When it settles, I hug the trigger. LikeBAM! With no movement of my target, no trace of a hit, I aim and shoot again. BAM! I continue to load the magazine and shoot. My woodchuck hasn’t budged. Greg fires his gun and with each shot creates small clouds of smoke before his target.

When our bullets are spent, we walk together around the pond to inspect the targets. Surprisingly, the bullets sped through mine without moving it and I’ve hit the woodchuck’s belly twenty-six out of twenty-eight times. Pleased with myself, I’m hooting and cheering. Until we remove the targets from the base of the willow.

“Oh. No,” I wail, “I’ve been shooting clear through to the tree. We’re killing the tree.”

“Oh, well. ‘Goes with the territory,” he shrugs.

Some things, like the differences in our respect for life and living things, will never jive. I say a silent apology to the tree and then follow Greg into the kitchen. He takes the two rib-eye steaks I got for our supper, pierces them several times, plants them in plastic zip-lock bags, and marinates them in Johnny Walker whisky. He pours two glasses of the whisky over ice.

“Did Marika ever shoot? What’s the best prank you ever pulled on Marika?” I ask, thinking I’ve got him relaxed and ready to chat. “What would you fight for or even die for?”

“Mom. Just enjoy the Johnnie Walker. Okay?” And then, “Do you still have my extra passport photo somewhere? I need it back. I’ve got a job in Afghanistan as soon as I get my papers cleared.” He’s leaving again. Whatever holiday I’ve been avoiding is now totally shot.

Later that night, on the first Christmas Eve without my daughter, the single drawer of the small night table next to my bed is stuck open. I rarely use this drawer but I had rummaged through it for Greg’s passport photo. Now the drawer is jammed and I can’t get it to close shut. I slam it and it breaks. When I wrench it back out, a tiny green cloth packet falls to the floor, and I remember a Christmas long ago when Marika had no gift to give me. She had scurried upstairs, bounced back down, and handed me this small pouch of jeweled sequins. Now I empty the contents into my hand. Sparkling butterfly-light jewels catch the lamplight that blurs through tears. The remaining sparse contents of the broken drawer lay on the floor. And in the middle of the small mess, bound with shiny red holiday ribbon, sits a tiny book written and illustrated by Marika in 2001, when she was eleven years old.

Book of Wonderful Memories. From: Marika. J.W. To: Robin Botie

1.The costume parade. You were there for me every step of the way! I’ll never forget your face when I got 4th place. You were so happy! 2.That one teddy bear that you would look at when we were fighting and tell me a story of you. Mom … 5.Even with the most boring books, it seems so exciting with your voice. … 6.When I’m scared you are always there for me … 8.Always loveing even when I’m a brat.

Mareek! Are you here? I cry out. Are you helping me get through Christmas? What the heck am I doing in this drawer anyway? It’s almost midnight and I’m holding the most precious gift, now received twice over. Why does it feel like you’re watching me? Sometimes it’s hard not to believe in ghosts, in after-life. Here I am, holding this tiny book you made ten years ago, before all the road trips, before cancer. Before our mother/daughter divide. Ten years ago when you adored me—Maybe you never stopped adoring me—Maybe you just stopped showing it.

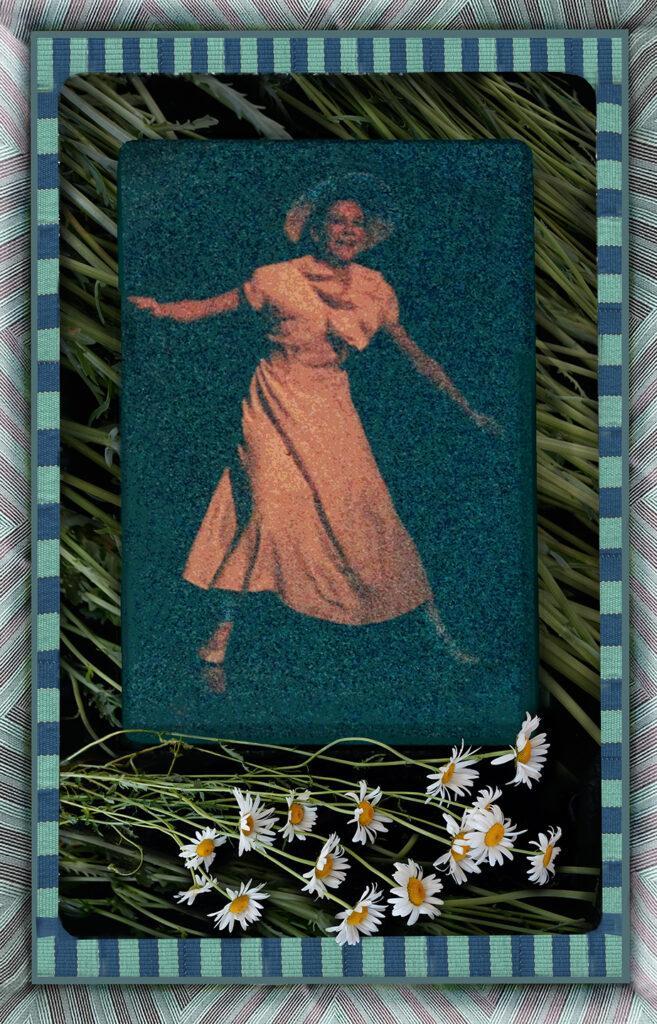

She’d made me a book. And now I am making a book for her. She wrote. So I’m writing. Words are my new medium and I’m using them to paint our portrait, mixing words like I used to mix colors. All the sweet or savory, whispering or roaring, bland or bewitching words that dance in my mind. Like : meandering, infinitesimal, crimson, petechiae…. Reading my book aloud at the Feed and Reads, occasionally I glance up from the pages to peek at my audience, their jaws dropped and eyes begging me to continue. My gift to Marika, I tell myself. Really, though, she has gifted me, and is gifting me still.

My first manuscript is a plot-less lament to my dead daughter. But that doesn’t matter. Because, daily, I lose myself and find myself in what I write. Some new determination to live, lives on. And I feel hope. It’s back. And hope implies future. So I continue to write, and look forward to the sharing. And I love my book like it’s my daughter.