Days after the calling hours, I enlist Rachel’s help to go through Marika’s belongings. Rachel wants me to meet her boyfriend. So the next week, still in a daze, I take the two of them out to dinner. Dressed up, made up, and manicured with acrylic French tips, Rachel glows, reminding me of Marika. For a moment I feel like the mother of a daughter again.

Days after the calling hours, I enlist Rachel’s help to go through Marika’s belongings. Rachel wants me to meet her boyfriend. So the next week, still in a daze, I take the two of them out to dinner. Dressed up, made up, and manicured with acrylic French tips, Rachel glows, reminding me of Marika. For a moment I feel like the mother of a daughter again.

“May I see your wine list, please?” I ask the server, intending to order a bottle of wine for the table, the way I do when I go out with my girlfriends or family.

“I’ll have a Long Island Iced Tea,” Rachel says. I try to remember if that’s the drink with five different liquors. Tequila, I think. Vodka. Rum and gin and…. I’m surprised. But she’s of age, so I forget about it. Until she orders a third Iced Tea before our meal of steaks, fries, and giant chocolate chip cookie topped with ice cream is over. Does she always drink like this, I wonder? Did Marika drink like this? At that point, though, I get distracted by car talk. I sell Marika’s car to Rachel’s boyfriend.

Days later, I don’t empty the car or look to see what’s inside. The creaking sound of its door and smell of the strawberry-kiwi air freshener over the dash could release a torrent of memories. Car gone. That’s when I really know for sure Marika isn’t coming back. I spend the next three months running away as fast and as far as I can. I would have run out of my skin if I could have.

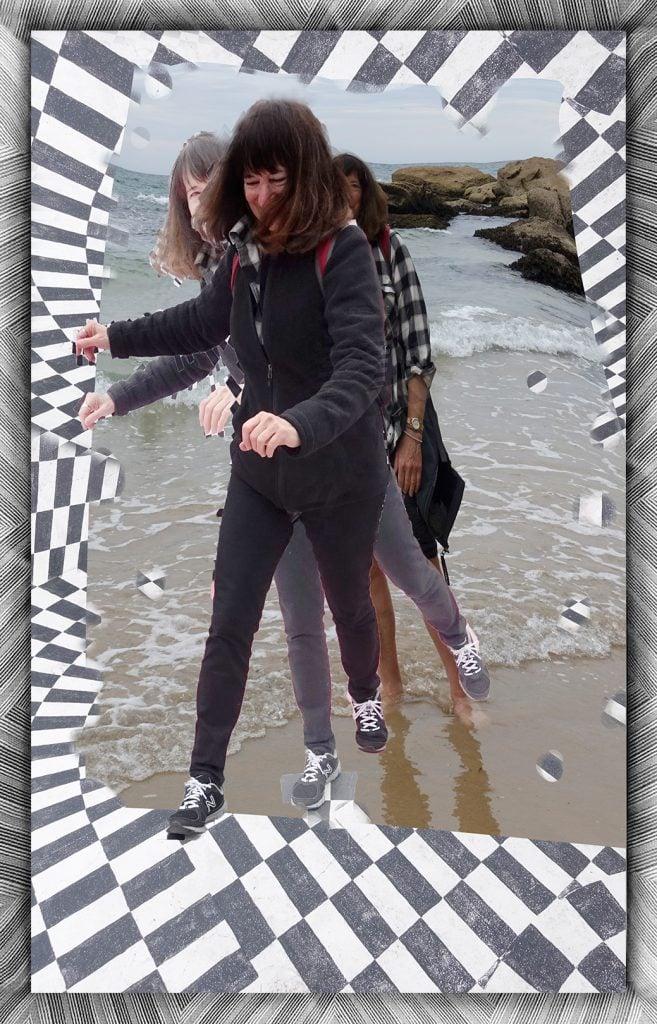

In the spring of 2011, England’s Prince William marries Kate Middleton, the Federal Government threatens to shut down, Osama bin Laden is killed, and New York legalizes same sex marriage. But I’m oblivious, racing to catch planes and scanning the crowds of fellow travelers for Marika’s face. It doesn’t matter what’s going on in the world or where I land. Finland. France. Anywhere but home. She is no longer there. The presence I felt so strongly the first days after her death dissipated shortly after I brought home her life-sized portrait and began talking to it. Maybe when I return to the house again she’ll be back. Maybe if I set her free, set her belongings free, she will come back to me. So I’m on a mission to toss Marika’s earrings and bracelets into oceans all over the earth. Does this have to make sense? Will anything make sense ever again?

Then suddenly it’s June and I’m back in the States. I wake up in my car one day, lost somewhere between my mother’s home in Western Massachusetts and my sister Laurie’s in the east. And I’m desperate to find a post office so I can mail more of Marika’s jewels to places she’d have visited. She wanted to see Greece and Ireland. She’d have loved Colorado. So I send out bits and pieces of her to friends all over the world. It offers me some vague comfort, like she is still here, like some part of her is just off traveling someplace beyond my reach.

Please Share on your Social Media

Another huge sob.This is powerful and amazing that you let go of her stuff so quickly. I did the same with all his “sick” clothes and bedding (and bed), but held on to most everything else and pulled in. I didn’t want to go anywhere except my forest which is where I seek refuge again during this quarantine.

I wonder if you, too, are being constantly reminded these days of your cancer journey with Vic. All the talk of ventilators, having to wear masks to protect ourselves from germs, watching people I encounter for signs of colds and coughing, and feeling in awe of all the healthcare workers I see on the news—it takes me back to those days of being my daughter’s caregiver. Only now, I’m my own caregiver. And the cancer is now coronavirus. And I’m singing Happy Birthday to Marika, twice, while washing my hands, several times a day. This social distancing suits me. I happily photoshop all day long (after morning hike) and am learning to love having all this time to illustrate small portions of my manuscript all the time. I guess that is MY forest where I seek refuge. Keep safe, Elaine.

Huge sob

Maybe that explains the “Waaaah!” response from previous week, Lucy. Brutal pieces, these. It gets better, I promise. I wouldn’t be here today, couldn’t have survived, if it didn’t get better somewhat.