People always tell me what I want to do is impossible. And I have to wonder, what do they see when they look at me? Do I look so inept? How many times on this Australia trip have I been told I wouldn’t be able to do something? To walk to Bells Beach, to get to Port Campbell on a Tuesday, to travel without a car, … to spread ashes in the ocean without drowning myself.

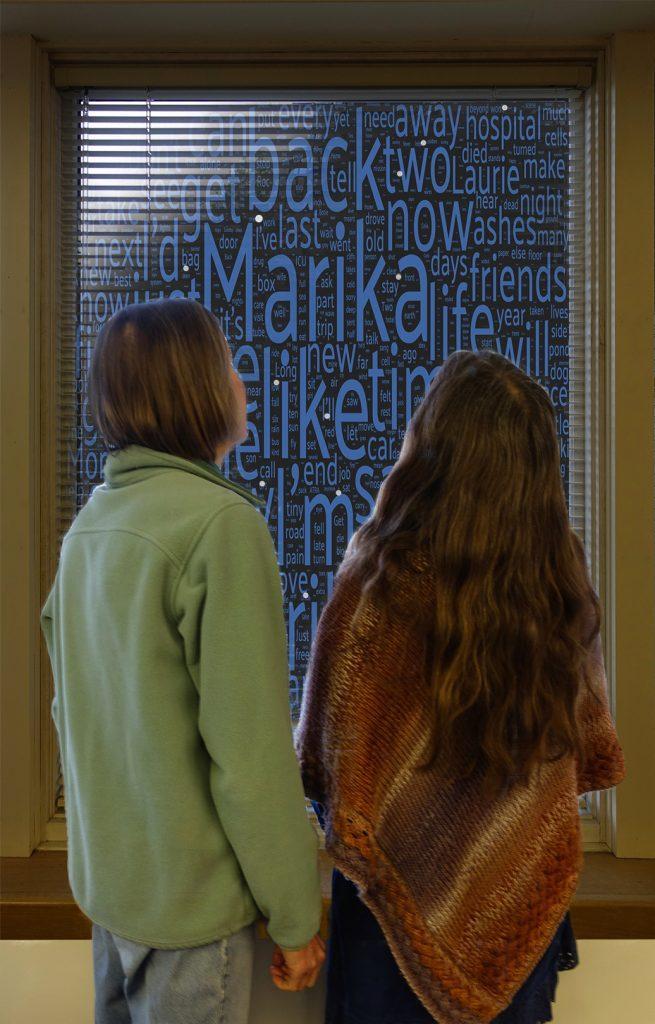

“Impossible,” I’d also heard back home, coming upon the first anniversary of Marika’s death, “You can’t keep a relationship with someone who is dead.” But I was talking with my dead daughter every day and every night. Speaking to her came naturally to me after she died. How could something so comforting be impossible?

Sadly, watching the twilight turn to night over Two Mile Bay, I regret how often I, myself, have similarly, close-mindedly shot down other’s ideas. I recall a time years ago, in the middle of winter when my father had taken my sisters, and me, and my children on a vacation to a Caribbean Island. Arriving on a balmy night, the sisters and children immediately headed for the beach where we kicked off our shoes and danced in the starry dark. Until my father, flustered on the boardwalk, said, “You can’t be on the beach at night,” and then I, myself, ruined the joyful moment saying, “Okay, everybody to bed now.”

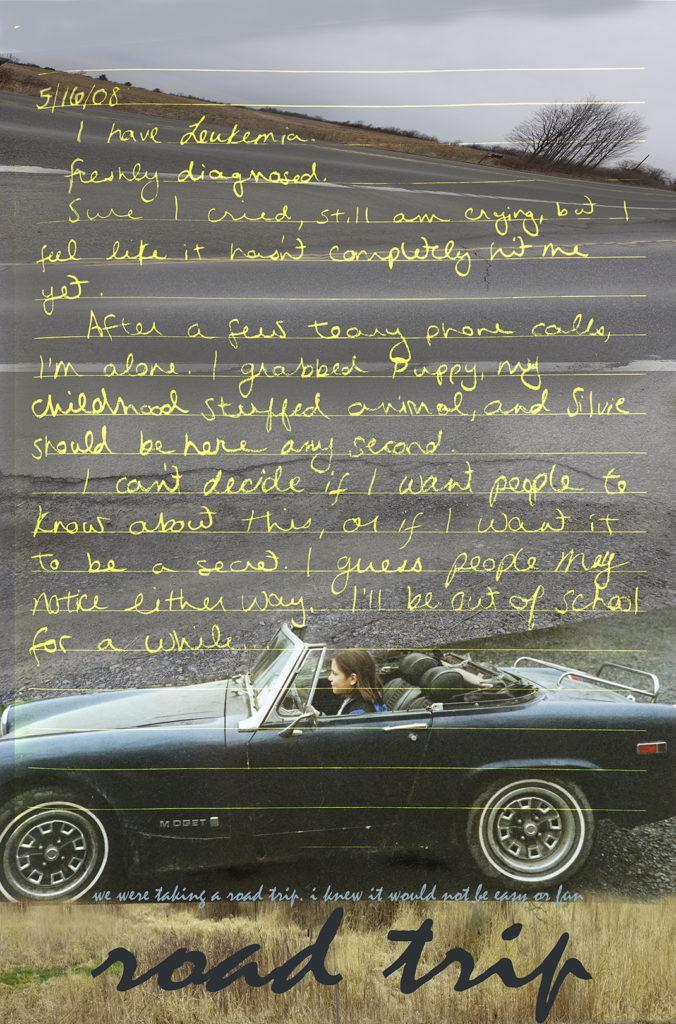

“Impossible. No way,” I’d decreed when sixteen-year old Marika begged to go off on road trips with friends. To young Marika on the edge of our pond or hanging out in the surf with her boogey board, I would holler, “Don’t fall in” and “Don’t go out too far” and “You wanna do WHAT?” Objections. Directives. Were those my only songs all those years? So much negativity, controlling, and prejudging. This dragged up a deep sadness, because there were few relaxed, neutral communications with my daughter that I could remember.

“Mom, I wanna duet. Let’s do Chopsticks,” Marika used to beg me as a kid. When I could put it off no longer, we sat close on the piano bench and she’d begin plunking keys. To duet is to take part in an activity with another in a way that achieves a harmonious effect. A unity, of sorts. But for me, keeping in sync with someone else was like trying to catch the first step on a fast-moving escalator.

“I can’t,” I’d say and give up. She asked me to play only a few times more before she gave up as well.

In early spring of 2012, my daughter’s been dead a whole year, and suddenly I need to duet with her. Not just our everyday exchanges where I’d sing, “Don’t do this” and “You can’t do that,” and she’d follow with her refrains, “Mom, what the—” and “Get a life, Mom.”

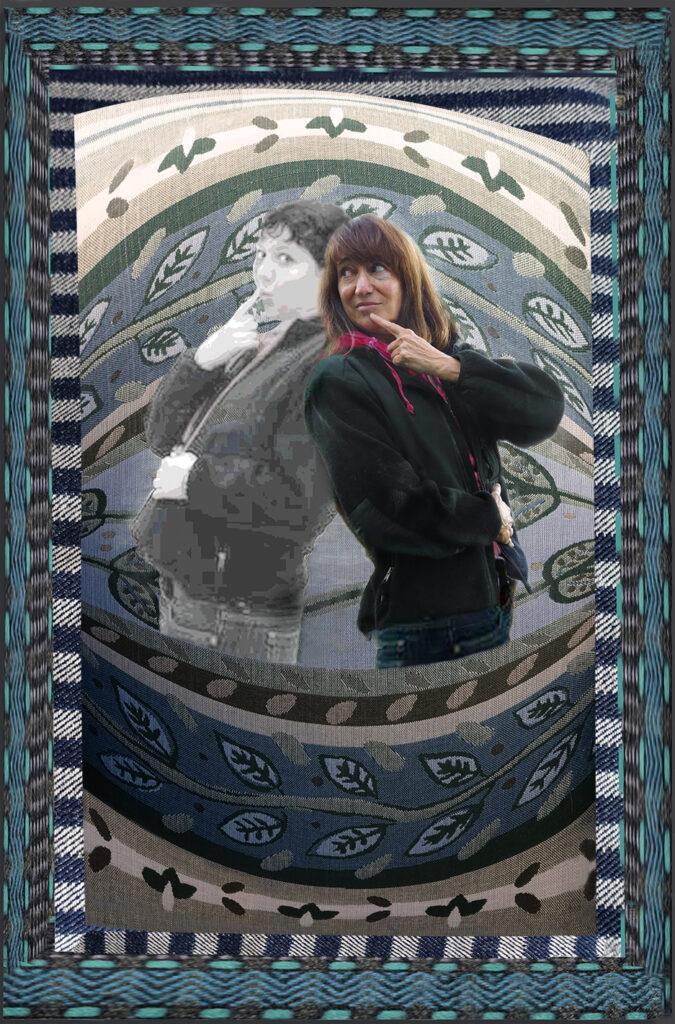

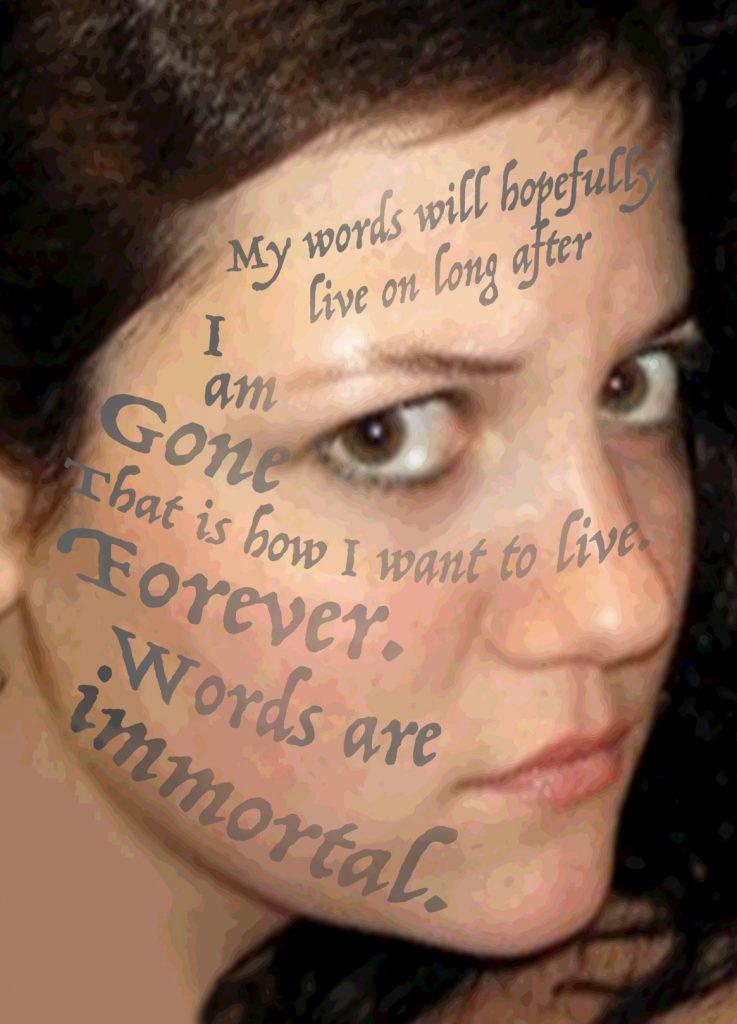

“You can’t have a duet with a dead person,” a friend insists. And I know it’s too late to have the conversations and exchanges Marika and I should have had. But, reading Marika’s poems aloud, I hear her voice. Her songs swish around in my head. Now she’s daring me to have a duet and it’s impossible to ignore. So for hours every day and into the night I read and echo her words, and scribble out my own. It’s like when we used to fight. We were mostly saying the same thing but we were bouncing against one another from two opposite planets. And now she is saying, “I will not follow you. You will have to follow me.” So I do, recognizing that we are each of us stubbornly strong women. Beautiful trouble, I used to call Marika. I had never before considered myself strong or beautiful. But something is growing in me. Something’s shifted. Somehow our relationship is changing and it’s like I’ve finally grown up. She’s grown up. And we’ve melted into one. I follow Marika’s words to find her, to find myself. To find us: who are we now, and what we could possibly carry on together as time goes on.

Line by line, I read her poems and responded. It felt like duetting. As if we were playing an elaborate game of checkers or tic-tac-toe that depended on each other’s moves. Marika’s words. My words. Marika’s. Mine. Before leaving for Australia, I pasted our words together on paper. And then I shared them aloud at the last Feed and Read, enlisting my friend Paula’s help for Marika’s part. A duet with my daughter who died. Not only was it not impossible; for me it was like delivering a divine opus.

So here, on my last night on the Great Ocean Road, I know, when one is doing something, doing anything to climb up out of a rut, anything’s possible. I understand now that to squash a person’s efforts may be to shoot the very thing that keeps her breathing. I’ve learned that anything’s possible with people cheering you on. And that getting from Port Campbell to Melbourne before dark on a Monday, a day when the buses are running, has to be possible. With all the connections between buses and trains, I could travel all day and still not see Melbourne until nightfall. By car, it’s only a four-hour ride. So Eleanor at the Loch Ard Motor Inn operates on the computer and on the phone. She finally shouts out from the front door and manages to arrange a ride to Melbourne for me with her son’s friend, Cannonball.

In the morning, I am packed and ready to move on. Locking the little room with the bay view for the last time, I count my resources: the rolling suitcase; the pack with Puppy and the last quarter of Marika’s ashes; and the iPad, my link to friends and family back home who have faith by this point that I might really pull this mission off. And now I have Cannonball.

Maybe he’s named for his gut, barely hidden under a soiled tee shirt that says QUIRKS three times in large letters. He has a long black ponytail, no front teeth, orange fingernail polish, and a car with bald tires that is packed to the gills. He tells me, as we drive off, that first we have to stop at the pub.

Uh, what? The pub? You wanna WHAT? I’m suddenly seriously nauseous, and kicking myself for being, once more, in some weird stranger’s car. Until, half-listening to his words, I realize I’m shutting my mind and prejudging again. Turns out, it’s Cannonball’s moving day so he’s driving the “dog” of his fleet of cars. He’s returning to his kids in Melbourne after working many months at a good job on the coast. His teeth got totaled just days ago in a car accident involving tourists driving on the wrong side of the road. And he has to return the keys and pay the last of his rent at the pub before leaving Port Campbell for good. There’s still no accounting for his orange nail polish but the tiny details don’t matter once I warm to his generosity and kindness. He does most of the talking during the long drive, pointing out various sights along the way, and finally drops me off in Melbourne, in sunlight, near my hotel. An engineer, well paid and compensated for his travel, Cannonball won’t take money from me. I shake his hand gratefully, because anything’s possible, and that could’ve easily turned out any-other-which way than it did.