“Oh no! It’s gone,” I cry out in the middle of photography class. “All my work is lost. It just disappeared.” My heart stops and I stare in disbelief at an empty computer screen.

“Just hit Float All In Windows,” says Harry, the instructor. In a click my precious “lost” images are recovered and neatly lined up awaiting my next command. “You don’t lose anything in Photoshop,” Harry tells me. “It’s all right there. It’s just hidden in another layer.”

Layers. Photoshop is endlessly full of layers. They drive me crazy. They also intrigue me. Adjustment layers, restoration layers, background and mask layers … the opportunities to lose and find things are endless.

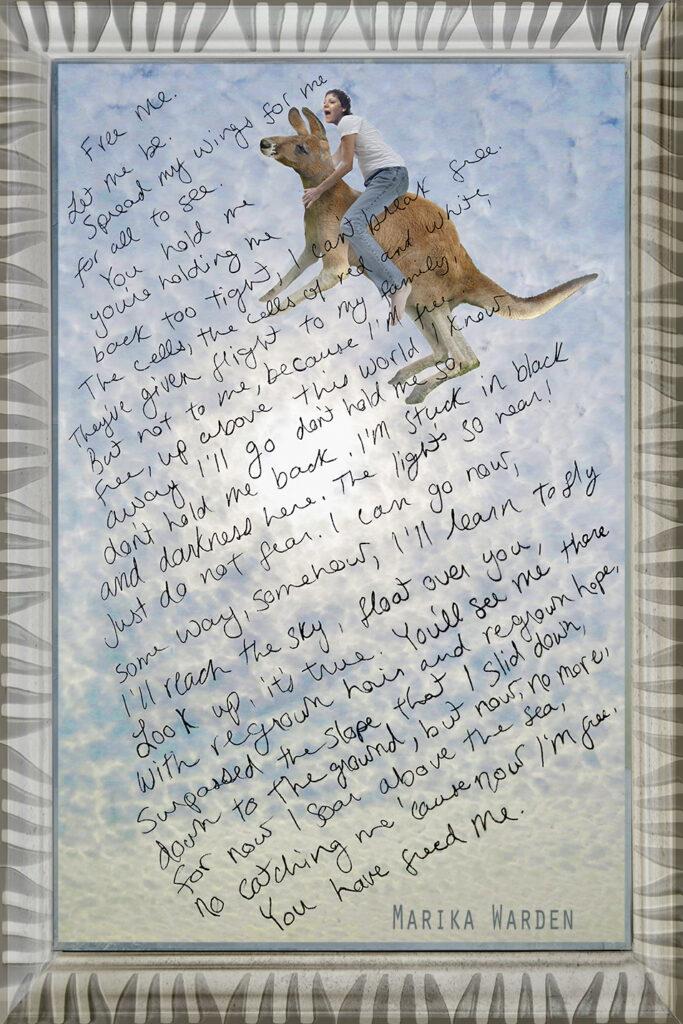

Grief is endless. But grief changes. The cumulonimbus clouds that hung on me have turned into delicate cirrus wisps high over Cayuga Lake. The frozen mud has thawed, and I can breathe once more. I’m light. In love with fragile, beautiful, unpredictable life. And it’s April again. The geese are back. But they don’t stay to nest. No, now I have ducks. And Marika. She’s here. In Ithaca, with me, still. But it’s different.

Around town, by the lake and gorges, and the Downtown Commons, I am warmed remembering this was her home. She was here. Some part of her is still here. Out with friends, in restaurants on Aurora Street, I clink my wineglass and make a silent toast. Walking her dog late at night in the driveway, I sing to her, and ask, “What exceptional thing will we do tomorrow, Mareek?” And in the house, where her image smiles back at me from every corner, I light a candle over dinner, saying, “One for good luck,” meaning, one for Marika.

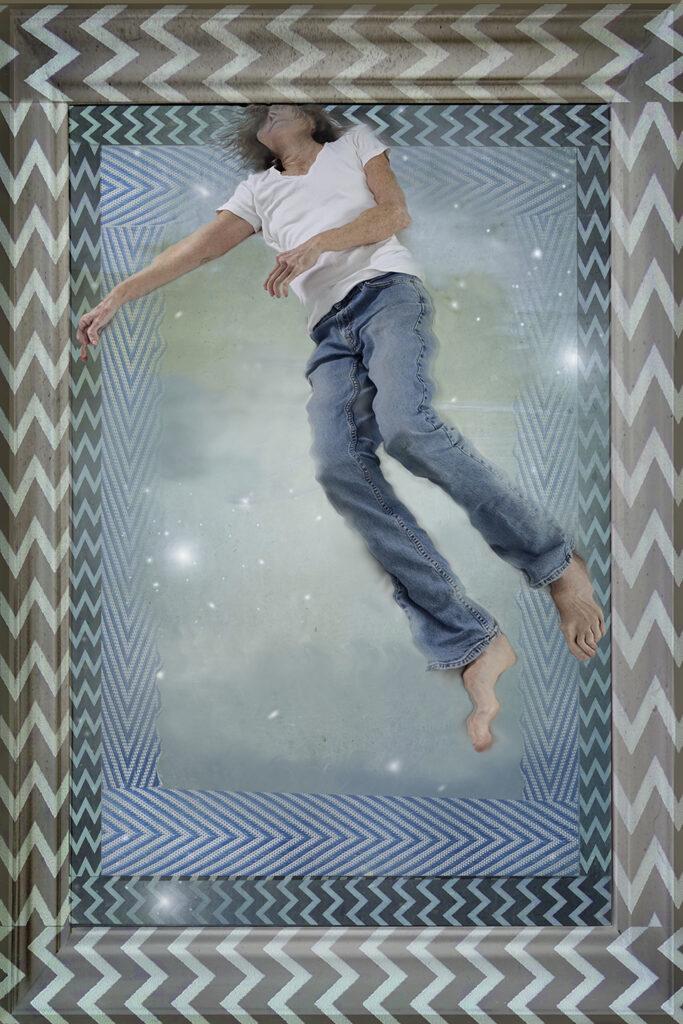

Once in a while she appears in my dreams: I open a car door and she is in the back seat. She’s walking the Commons with a companion. Or we’re jogging. Or shopping. She is always young, healthy, and bright as the sun.

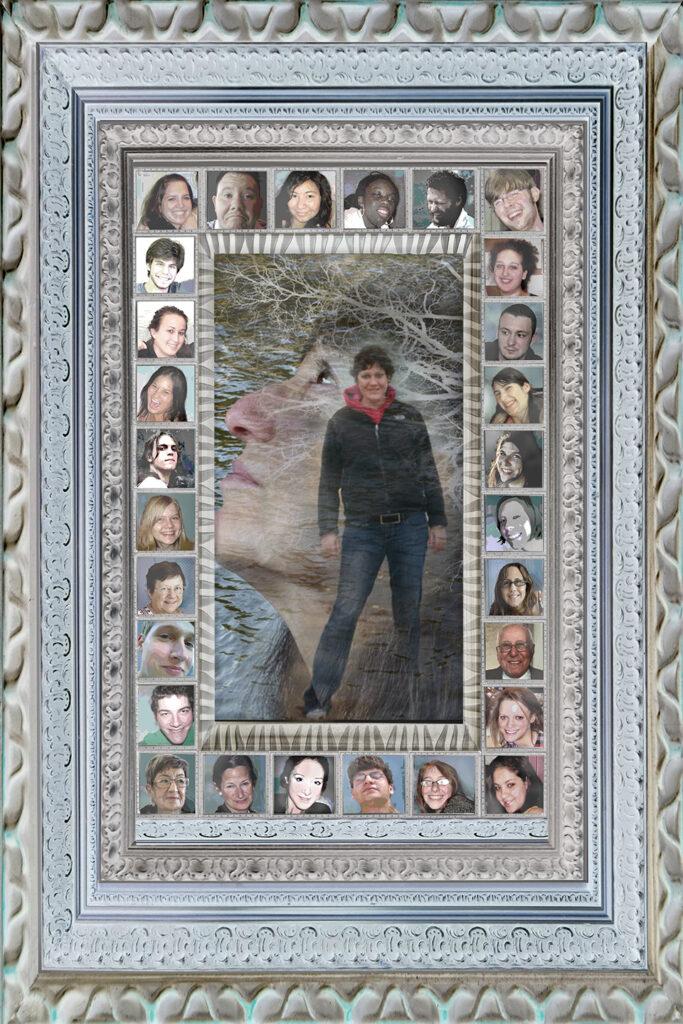

“I saw her, Suki,” I say on waking in the early hours of morning. Then I let the dream fade away as Suki rolls over for a belly-rub. I no longer keep my dreams in a notebook. I don’t need to look for Marika. She is hidden in the myriad of layers surrounding me. She is inside me. She’s in the shadows and corners, the undefined edges of space between what one sees and what one imagines. Close by, but beneath layers. Layers I often overlook in my continual quest to find the too-big answers. Layers that occasionally yield a tiny earring lost long ago in the carpet under her bed. Layers that tease me with the sounds of her trying on new jeans in the dressing room across from mine, or that suddenly flash her name or face on the computer. That stop me each time I pass a sushi place. The layers of ash and earth, of galaxies in the universe, of the internet. Layers of memories and dreams. Of who I am and who I was. Between my joy and my sorrow. There are layers where what we love and thought we lost can be found. And kept. Or set free. So many layers. So many choices. We can plummet into despair missing our loved ones—missing out on the joys in our own lives—or we can allow our love to be a source of new energy, creativity, and strength.

I am my own lifeguard now and I choose to guard Marika’s life as I guard my own. She is part of me. Pain and death are layers of my experience. They are not things to get over or through. My life has been shaped as much by her dying as it has been by having children, by being my soldier-father’s daughter, by fearing the ocean and becoming a lifeguard anyway. By allowing Marika to be my beacon of light. We’re in this together. In almost everything I do, I am duetting with my daughter who died. This is who I am now. This is how I am holding my self together. Together with my daughter.

And as I venture into the next chapters of my life, I take her with me. She will always be here, somewhere in another layer, not too far. Maybe right in front of my nose.

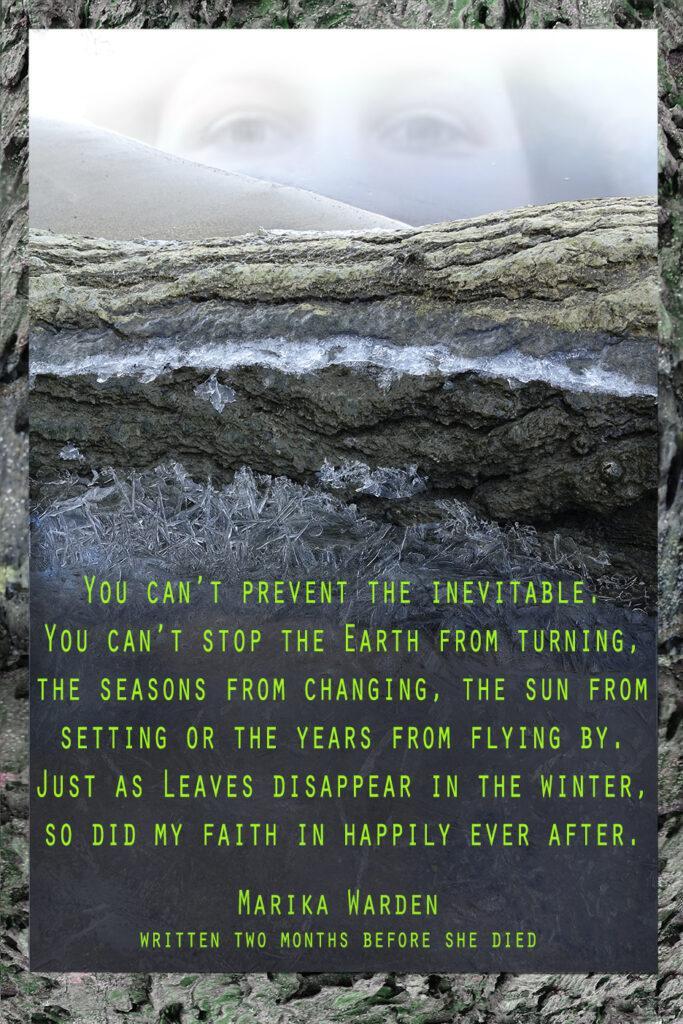

It is May 2013. A year ago, on the way back from Australia, I fell and broke that nose. It’s healed now. There was a lot of time to figure out that healing means more than simply being brought back to the original condition. I still have a big nose, but these days it sits quietly in the middle of my face and does not bully my other features for attention. When it was set, it lost some of its hook. It lost lots of its prominence in my mind. Now it’s more crooked but it’s mine and it fits.

These days, when I look in the mirror I see my eyes first. They are eyes that scan life down to the tiniest pixels. They sweep the sky. These eyes watched my daughter take her last breath. And watched my son turn into a man. Someday these eyes may witness the first breaths of a grandchild. Or they may again seek the departing soul of another loved one. My eyes have earned their furrowed trails of lines that branch out and upwards. No longer shuttered, these eyes are ever on the lookout for the best times.

“I was fragile, yet strong, among all of the smiling faces around me

making a pool with me in the center of all of the surrounding energy.”

Marika wrote this. These were the last of her words I found. Days before I left to scatter her ashes in Australia, I’d scoured the house to have all of her to take with me. These words were in her attic loft, in a notebook with nothing written before or after them. As though she was starting a new story.

As though she was starting my new story.