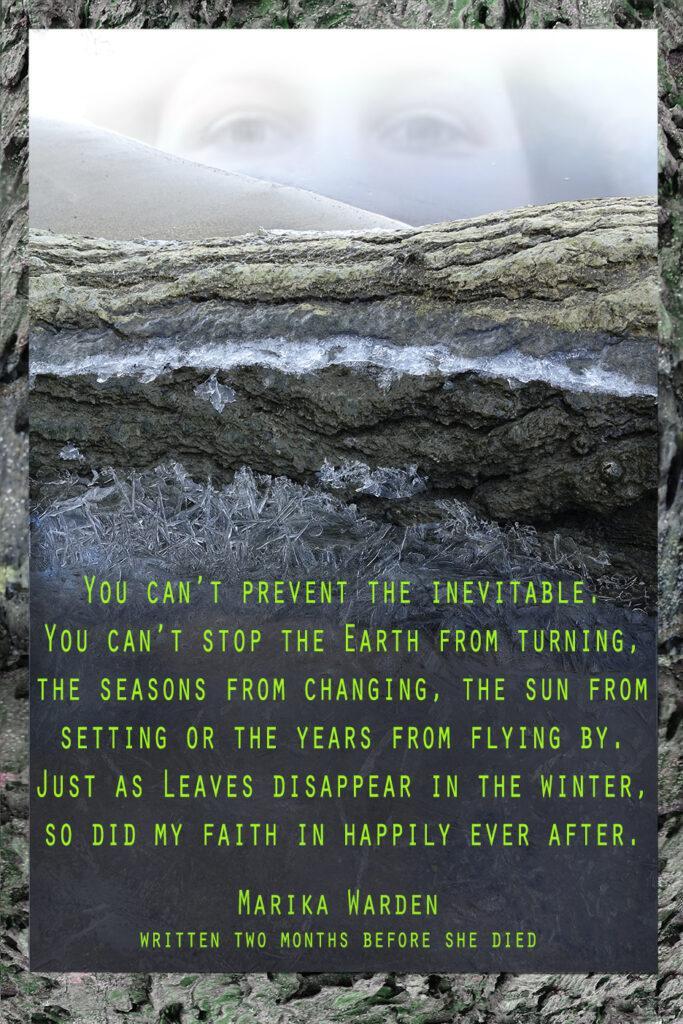

Warning: The following is an account of witnessing my daughter’s last breaths. A beautiful but very sad memory, it was important to me to include it here. But if you do not want to be faced with intense sadness you might want to simply enjoy my illustration and forego the reading this week.

As a mother preparing for my daughter’s impending death, I needed to see the beautiful life I’d brought into the world carefully wrapped up and tucked in snuggly. This was really happening. There was no stopping it, no stopping time. It was past the time for hope.

Marika’s father and I had promised her peace, that we wouldn’t fight. We had worked hard to hold things together. But on Friday, March 4, 2011, the day we were to let her go, we were both on the dark, uneven edges of our individual cliffs. We’d agreed to “have it happen” at one o’clock. But suddenly, in the middle of the morning, her father announced he couldn’t stand it any longer; it had to happen right then. His wife couldn’t bear to watch him suffer. So there we were. The time that had been ticking away was suddenly taken away.

The nurses asked us to leave. We would be called back soon to be with her for the end. Marika’s father, his wife, my son, and my friend Celia slipped quietly out the glass door. I did not. The preparations for disengagement of life support would not be pretty. But I wanted to be there anyway. I held onto Marika’s feet, and looked the nurses straight in the eyes through a blur of tears.

“I’ve been with her through everything else,” I said, trying to collect myself in between gasps, “I want to stay.” And they invited me to come closer to where Marika lay in the milky light of the overhead fixture that hummed on center stage. There, the nurses, like Disney bluebirds attending Sleeping Beauty, flitted about undressing ribbons of tubing, tying up cords, primping and preening her. They fidgeted with the monitors. Marika looked peaceful and trusting.

Are you dreaming, Mareek? I said to her, in my head. My Hurricane Marika, where’s your thunder now? You know you could tear out these lines and rip apart these bags of blood and drugs. You could throw the IV stands javelin-style through the glass walls and make torrential waves shatter and smash everything. You’re still alive.

I wrapped my hand around her forearm. The nurses checked her eyes one more time, shining a small flashlight under her lids. She had the warmest hazel eyes. It’s okay, Mareek.

It wasn’t okay. I hated hearing myself say those words. That was something I said when she didn’t win her soccer game or didn’t get the grade she’d expected on a school project. ‘It’s okay’ meant she’d get over it and things would work out better next time.

They unhooked the bags of meds draped up and down the twin IV stands, leaving only the painkillers. I watched Marika’s perfectly arched eyebrows for signs of discomfort as they swabbed and then suctioned her mouth. The monitors ticked. After weeks of constantly checking their displays, I couldn’t stop peeking at the blinking green digits.

There was no plug to pull. There was no lethal injection. It was simply a matter of removing the air that was being pumped in. First the nurses peeled the tape from her face and gently wiped the tape marks from her chin and cheeks. Then they pulled out the breathing tube that delivered air, and stuck another tube deep into her mouth to suction out her throat once more. I heard the air hissing and then sucking. The monotonous hum, ticking, and beeps of the monitors comforted me; they meant she was still here. The air tube was gone now and she breathed on her own. I inhaled and exhaled every breath with her. Keep breathing, Mareek. Breathe. Breathe.

The others filed back in around us. Her father found the monitors too distracting, so a nurse turned them off. The screens that exhibited Marika’s life in glowing green turned dark. I felt for her pulse the way I learned as a lifeguard. Still strong.

You’re still breathing. Marika breathed seconds long enough for me to imagine her never stopping, long enough to imagine a chorus of nurses singing “mistake” and “miracle.”

How long can you keep breathing? Sweet breaths. Shallow breaths. She would not last long now.

You’re still here. I’m here. I need to focus, wake up. Watch. The now I know will be different on the other side of a blink.

Her mouth opened and took in no air this time. It closed and opened and hesitated. Her lips gently shut and opened and shut. And opened. Gently. Slowly.

Rest, Mareek. My Mareek, it’s okay. Her mouth was suspended open.

Rest. I love you. I had only her pulse. Pulse, no breathing. She was really going.

You are so beautiful. Pulse slowed.

Here. Still here. She was still here.

Here. Still.

Here.

Still.

Gone?

All gone?

Gone.

The clock said 12:28. I wanted the nurses to notice. It was 12:28 and Marika was gone.

I held her hand and stared: Lavender lined eyelids. Rosebud lips. The tiny spot that had been on her left chin forever. And I kept checking in with the clock, watching time fall away. March 4, 2011, 12:28 pm vanished. Just dropped off the planet. Overtaken by 12:29, and then 12:30. Wishing the whole world would end, I watched as the part of me that could sing and fly disappeared into nowhere. I waited. Like time might suddenly rewind. But wherever Marika was, her body was empty. She’d abandoned it. Some essence, some energy, was no longer there. This was not her. This was just her house. Her beautiful house with its scuffed walls and once-bright windows through which once emanated sweet songs. And sometimes thunder.

I hope there was light, Mareek. I hope you saw light.

Please, whoever or whatever you are out there—God? —please don’t deprive her of the light.