On our first night home after weeks in the hospital, Marika could hardly walk. So I settled her into the guestroom downstairs near my bedroom and left her with a commode, a walker, and a Harpo Marx-type bicycle horn.

“Mom, I’m not using that thing,” she said in her whisper of a voice, her throat still sore from the breathing tube.

“If you use the commode by the bed, you won’t have to call, but the horn’s there in case you want help getting to the bathroom,” I told her, not sure which of the three items she was referring to.

“Okay. You can go now,” she snarled, as I lingered in the doorway, knowing how desperately she wanted to be independent of me. Knowing she probably would not call. Then, in the early hours of the morning, I woke to a crash. Running from my room, I found her face down, flat on the floor, in a puddle of urine, unable to get up, tooth in lip, blood, tears. She had tried to walk unaided, and now she was on the floor. Bigger than I, and still bloated from all the IV hydration and steroids, I couldn’t lift her. There we were, stuck. Time to phone her father. I hated that I had to bother him again. I could just hear Laurie’s criticizing, “Robin, you have to stop calling him.” What did she know? Who else was going to help me get Marika off the floor at five in the morning? Marika would expect nothing else.

Her father had moved out of the house in 2002, when Marika was twelve. She adored him. But he could stir up even more of her anger than I did. He was clueless about her. Still, he loved her and tried to please her. He was clueless about me; but with me, he’d stopped trying long ago.

Story by Five-Year-Old Marika

Once there was a squirrel and a bunny that were friends.

They wanted to grow up and get married because they loved each other.

But how could they marry, they are both different animals?

But they loved each other so much that they grew up and got married anyways.

The End.

“Marika’s okay,” I blurted out to her father, first thing. “I’m sorry. She fell. I phoned the on-call doctors and they don’t think we need to go the hospital. I just can’t get her up off the floor,” I said. I wrapped blankets around her and we sat on the wet floor waiting for him.

“I lost my tooth,” she sobbed.

“It’s just chipped. The doc says we should call the dentist later this morning. I bet they can fix it easily. Maybe even today.” I tried to sound reassuring.

“Thanks for coming over. I’m so sorry,” I said, when her father arrived. I looked at him briefly to convince myself I’d once been married to him. For fifteen years. He was not happy about my summoning him so early but he gently picked Marika up and got her back into bed. I thought of my own father while he spent a few minutes with her. And then he let himself out of the house without a glance or word for me. I made another vow not to call or need anything from him ever again.

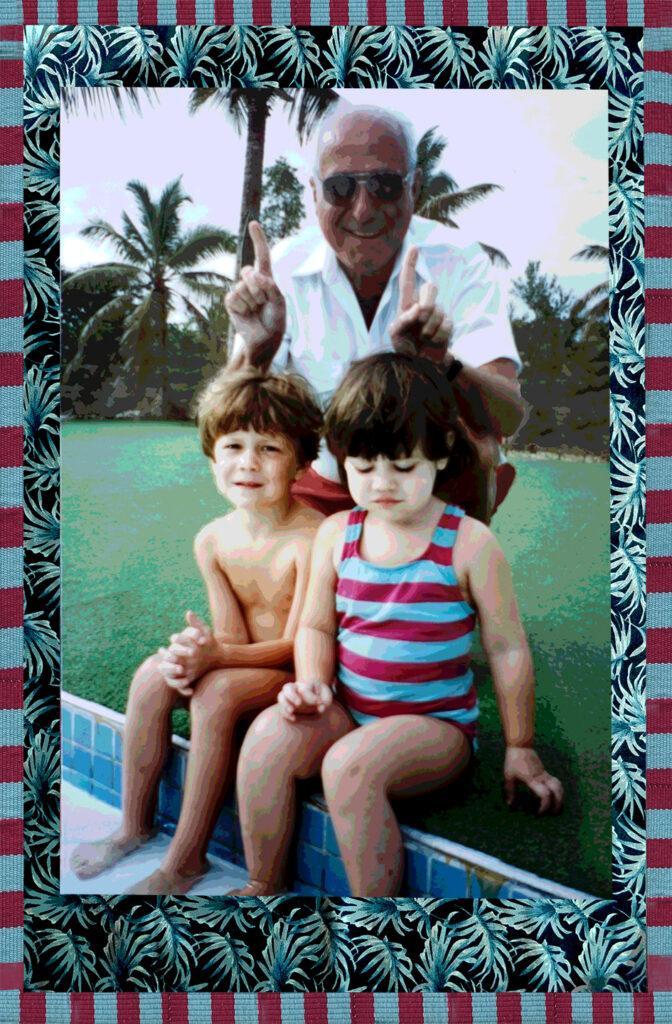

In my father’s home, I was Daughter Number One. That just meant I’d been around the longest of the three sisters. Often, with no reference to my name at all, he introduced me as, “My Number One Daughter.” When I was with my father, I was a princess. I didn’t have to worry about anything. Money was his currency of love, and he was generous. He started college funds for both my kids when they were born, and happily managed the account during Marika’s one year of college. At almost ninety, he still gave us family vacations and plane tickets to visit him, and dinners out in fancy restaurants. Then, at the beginning of this nightmare summer of 2009, he was hospitalized. His disease, some mysterious ailment, took control of everything. If I hadn’t been in the hospital with Marika, I would have been in the hospital in Florida, with him.

In September, Laurie and I visited our father. In the middle of the night in Delray Beach Hospital’s Intensive Care Unit, we watched him sleep, hooked to machines and monitors, sensor pads pasted all over his worn sun-browned body. His glasses, dentures, and hearing aids lay on the bedside table. He was beyond fixing.

He woke up annoyed, tossing his head from side to side, No. It was not supposed to be like this. He had planned and prepaid for his trip out of this world. The bills had been paid and a large loose-leaf binder was filled with his living will, advance directives, insurance information, and paperwork on everything he owned, including a prepaid cremation. Squinting, he looked at Laurie, Daughter Number Two, The Doctor. The one he’d designated as his healthcare proxy.

“It’s time,” he said, from his hollow mouth half hidden under an oxygen mask, not blinking his black marble eyes that caught great glints of light from the humming overhead fixture. “You,” he said turning to me, in a voice with no life left in it, “go home and take care of Marika.”

Hours later, the nurses moved him downstairs to the Hospice Unit. They herded his trembling younger brother, his broken-hearted sister, his three very different daughters, and all the rest of his family down elevators and hallways, into an empty, sunny room. Where was he, what was taking so long? Was he scared, I wondered? After a while they wheeled him in, unconscious and finally freed from all the life-supporting paraphernalia. He lasted long enough for me to say, “Thank you for making my life so rich, Dad.” I wanted the last words he heard to be “thank you.” I watched him take his last breath. Then he was gone. Dad. My first soldier.

After his funeral I went home to take care of Marika. And I made a promise to be his devoted Number One Daughter forever.