It was not like tucking her in. After my daughter’s last breaths and the moments the hospital staff reserved for the family’s final goodbyes, it was more like stripping down the Christmas tree. Off with the earrings. Then the navel ring, and the woven friendship band on her ankle. Off with the bracelet her brother brought back from Iraq. And stuffed Puppy, always held in the crook of her arm. Off. They said it all had to come off. I was left holding precious bits and pieces of my beautiful daughter, trying hard not to think about what would happen to her next.

Mom! Get over it! I heard Marika’s voice in my head. So I gave it all to her father. Except for Puppy. Almost threadbare Puppy was still warm from her. For a long quiet time I held Puppy, and stared at Marika’s empty house, getting used to the idea that she wasn’t there. And then I left, so they could take her beautiful house away.

They kept me busy. I don’t know who was with me, my friend Celia, my son? My sister? Didn’t matter, because Marika was not. I allowed myself to be led around. There was a walk to some local coffee shop to buy lots of gift cards that would be left in the Oncology Unit. There was packing up. Her things. My things. There was dinner in a restaurant where all I can remember is wondering how I could eat. And how Marika could not eat. How she, her body, her house, was stuck in the hospital, in the cold basement morgue while we were dining out. Her perfectly shaped eyebrows and red-painted toenails and all the rest of her that I’d never get to see again was now stuffed into some black plastic body-bag with not even a blanket to keep her cozy and warm. She had lain so still and vulnerable in the center of us. Helpless. And now she was alone in the cold dark, awaiting cremation.

I need to forget this last part. That is not how I want to remember her.

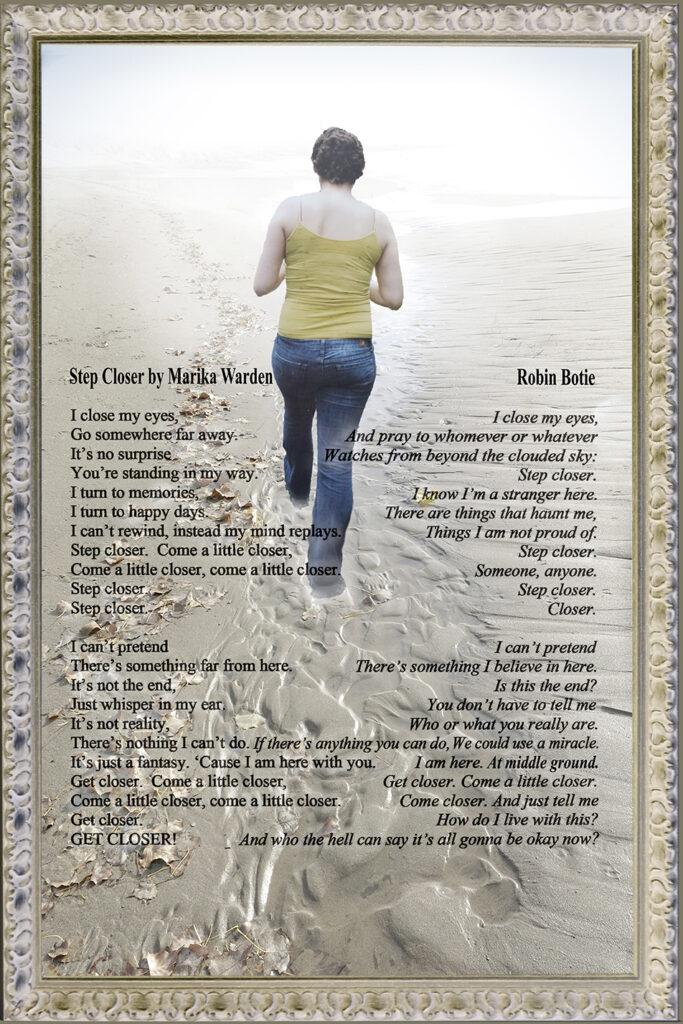

It was late. I returned to Hope Lodge without my hope. One last night in Rochester, that would forever be the city where I left Marika. Where I knew I’d have to return some day but knew I would never want to return. And that night, in my dream I swam with dolphins. I was overtaken by a wave that surprised me, rolling up from behind. It was too big, and I was too late to jump over it. So I was pulled down. Underwater, I collided with bricks and boulders and baby dolphins. Finally escaping the debris, bruised and battered, I floated, just dangling in the gray water while around me stars silently fell down. It was peaceful, so tempting to stay put. Was I prepared to die? I could not pretend this wasn’t happening. To me. Who was I now? I couldn’t remember. Did anyone need me anymore? No, the dolphins were gone. So I could go. I could rise above the bricks and leave the darkness behind. Wake up. Up and up. I could brave the wildest waves all the way home.

What have I done, I thought the next morning, upon awakening, when I couldn’t get up from the bed I’d sprung out of so many mornings to get to the hospital so Marika wouldn’t wake up alone. There was nothing to get up for. For the first time in my life I didn’t want to get up. I wanted to die.

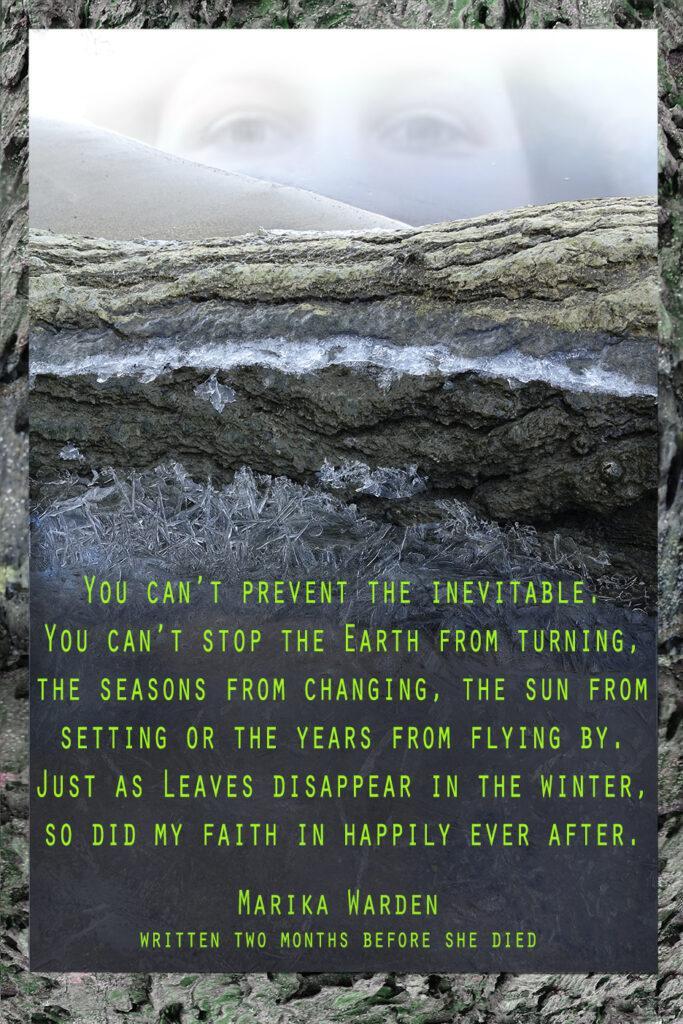

“You should write some final wishes. Just in case,” I’d told my daughter, like I was asking her to make a shopping list. It was back in November 2010, before her stem cell transplant. She was going to

“You should write some final wishes. Just in case,” I’d told my daughter, like I was asking her to make a shopping list. It was back in November 2010, before her stem cell transplant. She was going to