“What’s Middle Ground?” I asked Laurie, my sister-the-doctor, at the beginning of February 2011.

“Well, first of all, it’s not a medical term,” she said. “Basically, ‘Middle Ground’ refers to a shift in the treatment plan from an aggressive, do-anything-and-everything-necessary-to-keep-someone-alive approach to a more selective one. So, if Marika’s heart stops, we’re not going to shock it or pound on her chest, but if she gets a reasonably easy-to-treat condition (like a bladder infection or strep throat), we would go ahead and treat that. In a way, ‘Middle Ground’ is a bit like ‘Limbo’, the apartment Marika shares. It’s a place somewhere in between. Between knowing that you’re winning the war and when you get those first inklings that you’re going to lose. So you wait, in Limbo, for a sign, for some hint as to when or whether she can come up with one more miracle.”

“Oh,” I said, and Laurie could hear my dread.

“Middle Ground does not mean that anyone’s giving up,” she said, “but we all know it’s the first step toward that end, the end that no one is yet ready to acknowledge.”

So we were one step closer to that place into which I had not allowed myself to go. Outside, in the ground under the snow, tender tips of crocuses emerged into the wintry world before their time. They’d be gone before spring.

After the late night call from the Intensive Care Unit, when I got back to the hospital, Marika was floating in and out of consciousness. Sleeping Beauty, strung all over in plastic lines, was once again on center stage attended by nurses, aides, all types of technicians, and now, multiple teams. Besides the ICU docs, there was the somber cluster of oncology docs, a very animated squad of infectious disease docs, and a new tiptoeing team from Palliative Care. Bevies of doctors, social workers, and residents took turns entering and exiting her room, taking notes and quietly exchanging comments. A mysterious respiratory infection, they said; we wore masks and gowns around her now. No one really knew why her lungs were failing. When she became the least bit awake, she tried to speak. She yanked her cords and tried to climb out of bed. They gave her more drugs to quiet and contain her. She was fighting everything now.

“Please don’t speak to your daughter,” one of the nurses said to me shortly after I got back. “She is at maximum dosage levels for her sedation drugs, and when she hears you it is difficult to keep her sedated.”

“I can’t talk to her?” I wanted to make sure I’d heard right. In disbelief, I quietly rubbed Marika’s feet. But soon, when I whispered to a nurse, Marika heard me and woke. She pointed at me with an incriminating index finger, as if she could shoot a dagger straight through me. She lowered and then raised her hand, slowly, like a ghost, and suddenly gave me – The Finger.

The horrified nurse sedated her more. Hurt, and afraid of what Marika might do next, I kept quiet. But what I really wanted to do was shout to all the doctors and nurses, “Damn you all! She’s my daughter!” I moped for hours in a funk until I learned she’d given her father the same greeting earlier.

A day later, while I silently rubbed her feet, she opened her eyes.

“Mom!” she mouthed through her tubed and taped lips, looking straight at me. She extended her arms like she wanted to hug me. Her face scrunched up and turned red. Her mouth stretched the tape with a concave bottom lip. She was crying.

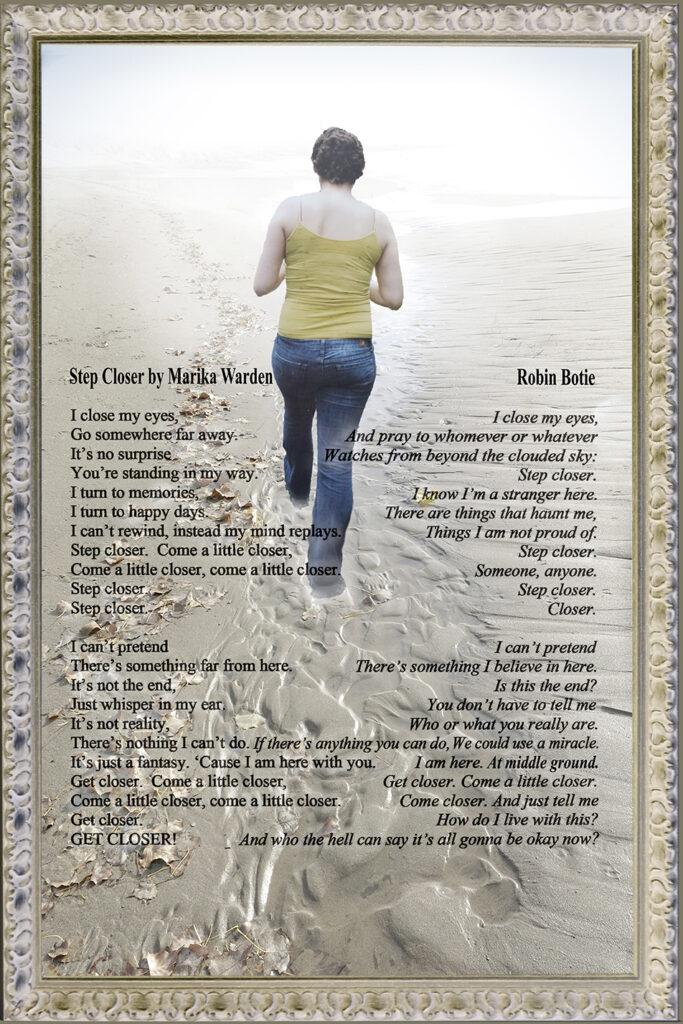

“Mareek,” I called, and left my station by her feet to step closer. “Oh, Mareek.” I reached out to hug her. But before I could touch her, the nurse stepped up the sedation. Marika’s eyes rolled back as her lids shut. Her arms dropped in slow motion. Her words, her thoughts, everything was snuffed out. I stood over the still form of my daughter, not able to remember the last time we’d hugged. In my mind I replayed the scene. She’d reached for me. Her eyes had said everything: “Mom, I’m scared. Hold me; help me. I’m sorry. Thank you. Mom, I love you.” I stared at her face and hugged myself, and returned to the foot of the bed. And then the nurse asked me not to rub her feet.

I was blind-sided. I stood there dumbfounded. Foot-rubs were my only connection to my daughter now. I couldn’t just let her lie there alone. She’d wanted to hug me.

Greg, on a tentative seventy-two hour notice to return to Afghanistan, came to Strong to say goodbye to his sister. Marika had known he was hired to go back as a security agent. But she was unconscious now and seemed to hear nothing. He didn’t stay long. He whispered goodbye and turned to go. Suddenly she lunged for him. She flew over the bedrails, tearing the lines that tethered her to the IVs. She grabbed her brother. In seconds, she was stopped and sedated some more.

Rachel arrived for a visit, and I darted out for a fast trip back to Ithaca. Rachel’s eye make-up, the tight skinny jeans and French-tipped nails made me realize how long it had been since I’d seen Marika up and dressed. I must hurry home, I told myself, to renew my driver’s license that would expire soon. Mostly though, I just needed to get out. I needed to drive far and fast.

Rachel ambled down the long hallway with a huge rainbow balloon trailing behind her. And two hours later, at the Motor Vehicle Bureau, I stood before a clerk who tried to get me to smile for the photo ID that would be with me for the next eight years. For eight years, my eyes in that photo would say, “Marika, we need a miracle now.” I faced the camera unable to think of anyone or anything else. Rachel sat with Marika and held her head, reading aloud the goodbye letter she had written, just in case. She drove back to Ithaca that evening, stopping at a liquor store for a bottle of Svedka Vodka to tide her over. I drove back to Strong early the next morning crunching on an apple to keep awake. The Big Meeting was scheduled with the Palliative Care team. So Greg drove to Strong, as did our social worker. My children’s father and his wife were already there. We were going to discuss The Middle Ground and “options,” things I wasn’t able to hear yet. I didn’t want to listen to any of these people. I just wanted to rub Marika’s red painted toes and watch for the tiniest twitch of her pale brow.