Barely twelve hours after landing in Ithaca, on my return from Australia, I fall head first and hard into my front door. And break my nose. Slowly, I lift myself up from the load I’d tried to carry into the house. Two huge garbage bags of cat-poop and soiled litter my cat-sitting friends had collected and sent back with the cat. The cat is still in the car, crying in his carrier. But I’m holding onto my head, barely able to breathe. A million things could have gone wrong in Australia, but they didn’t, and here I am, back on my own doorstep, losing my balance, falling apart.

My nose rains blood. Stars flash before my eyes. My fingers fumble blindly over the newly reactivated cell phone in an effort to reach someone for help. In the emergency room, I hold my face for hours as my memories of Australia evaporate. I beg the doctor for a new nose, a nose job. Impossible, he says, but he can fix the break. I wake up after the surgery wishing I could sleep through the healing. But even sleeping is difficult, done sitting up in a zero-gravity lawn chair parked next to the bed where cat and dog keep vigil over me and the tray of tissues, pills, and tippy-cup with water.

Over the next weeks my face turns the color of stormy oceans, then of green-gray grass, and finally a yellowish shade like wheat ready for harvest. I write feverishly as I nurse my nose. I watch the crazy geese on the pond. They hoot and honk. They do their nesting and protective dances all over again. From the south windows I follow the geese and the slow changing of the moon.

“Hey, Marika in-the-moon,” I call to her when it’s a full moon. When it’s a fingernail moon. On moonless nights when I walk her dog. “Do you see the moon, Suki?” I talk to the dog. I talk to Marika. I talk and sing to Marika’s moonbeam smile in her life-size photograph that hangs prominently in the middle of the house. It all helps.

Late spring nights I try to sleep, breathing through my mouth, as around the pond the songs of a thousand frogs echo in high peeps and low gunk-gunks. Frogs gulp and grunt. They scream into the dark night. Windows open or closed, it doesn’t matter though. Mostly I hear only the muddled noise of my mind trying to make sense of life’s events. I wait in the tumult of the night until the din dies down, or doesn’t.

The days are filled with friends who check on me, prying me from my writing. They listen. It helps to have friends, especially those who also have lost loved ones.

My friend Andrea dies. My children’s mentor. The one who believed in me. Cancer.

I lie on my back on the living room floor. Suki, my inherited dog, stands over me, engrossed by this new perspective. She pokes her inquisitive little nose into my still-sore face, and I can’t help but smile. Then she drops a squeak-toy on my chest and I explode into laughter. The sound of my own high-pitched squeals fascinates me. But it soon dissolves into a howling cry as I sink back into sorrow. Marika. Now Andrea. Has cancer always destroyed so many lives and I just never noticed? Suki stares at me, terrified. When I quiet down she licks the tears around my healing nose.

By the end of June my blog site is up. If I want to be a writer, I’m told, I need to have a website and write a weekly blog. And find followers on Facebook and Twitter. Oh, if Marika could see this. More and more, it seems, I’m living my daughter’s life. Only I’m shy and clueless as to social media. Communicating with strangers makes my neck muscles tense up and renders me almost wordless. But it is the only commitment I have, so I treat it like it’s my job; every Monday morning, no matter where I am or how I am, I publish an article. I reach out to family and friends, to Marika’s friends, and to people I have not yet met. I’m never sure of what to say. So I write the stories of my stumbling into deep holes of grief, and my attempts to crawl back out. In the hope it will help someone. We’ve all lost someone or something we loved. There’s life after loss. That’s all I’m trying to say. Or, it’s what I’m trying to believe.

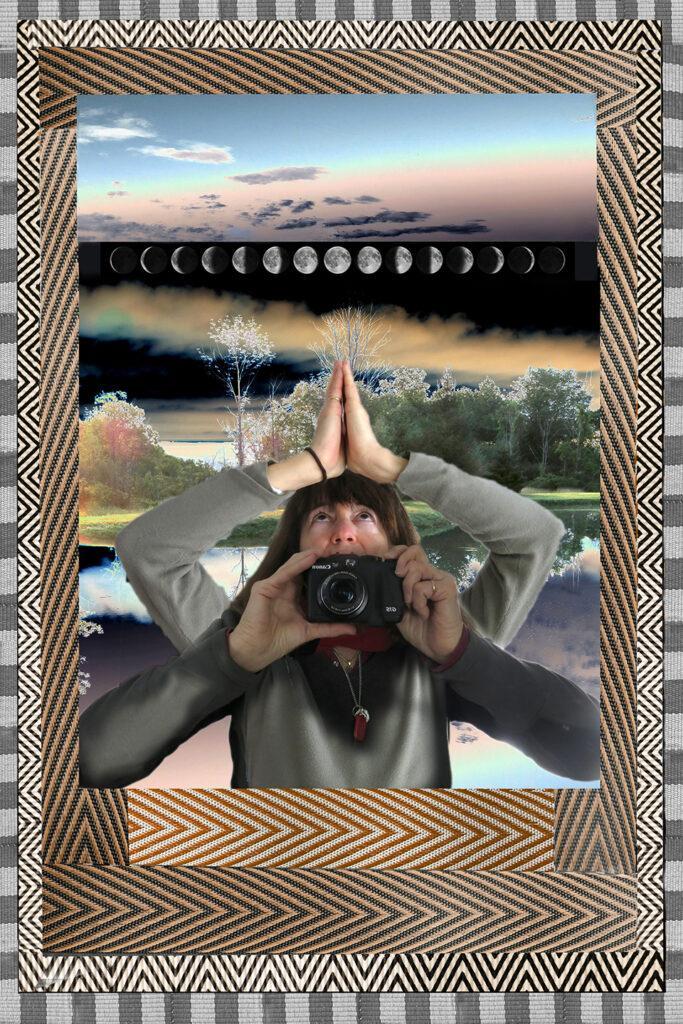

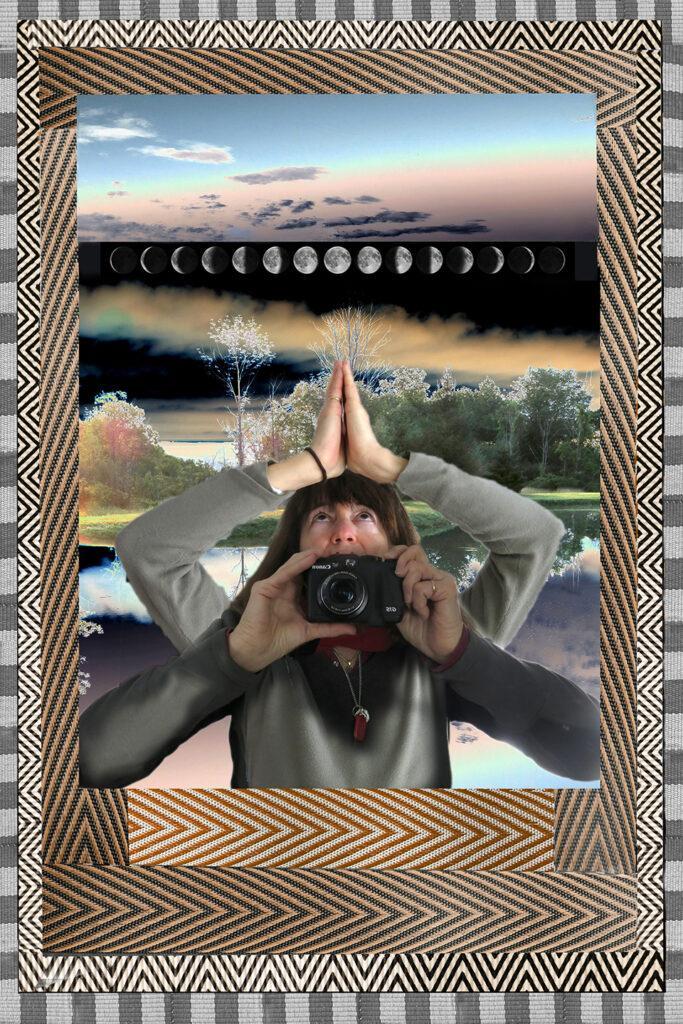

Way before our colliding with cancer I had developed an aversion to producing visual art. So I’m not sure what on earth led me to enroll in a Digital Photography course at Tompkins Cortland Community College in the fall after the Australia trip. I know nothing about photography. I’d borrowed a small point-and-shoot for Australia and could barely manage that. Computers and technology in general confound me. And here I am in a class with tech-savvy college students and a handful of retired folks with huge expensive cameras hanging around their necks like gigantic gaudy jewelry. The only thing I have going for me is my sense of design. And maybe my newly developed adventurous spirit born from the discovery that I need to actually do something in order to have something to write about in my blogs. But there’s this keen desire to breathe visible life into my memories of Marika. Like one huffs and puffs at the last embers of a dying campfire.

So I rent a digital camera from the school and photograph whatever sits still long enough for me to consider f-stops, shutter speeds, and ISO settings. Right off, I learn to photo-shop pale images of Marika’s face onto all my landscapes. Soon I’m ‘shopping away, trying to make impossible scenes appear somewhat real. I ‘shop Suki a dozen times all over the living room, in one picture. I enlarge Marika’s face until I can gaze into her life-sized eyes. Working in Photoshop is the closest I’ve come to finding peace. Or God, maybe. Time and troubles disappear when I ‘shop. The making of each picture is a prayer of gratitude. It’s comforting to me, if not actually useful. It’s challenging. I stagger out of class each week dizzy with new ideas. And in my weekly blogs I add photos to complement what I write.

It doesn’t take long to notice that my approaches to writing and photography differ. I work hard to find the exact words to describe reality. How something feels, smells, sounds, and tastes. I could never write fiction. But when I photo-shop, I can tell a more colorful story. So I tell the truth in words, but shamelessly stretch it in my photos. And I call the whole thing ‘healing.’

This is a vector portrait of my daughter Marika Joy Warden who was an aspiring young writer before she died of complications from cancer. It looks simple. But it took me forever to draw. Every shadow and highlight was painstakingly plotted out with a computer mouse-operated “pen tool” in the Adobe Acrobat Illustrator program.

This is a vector portrait of my daughter Marika Joy Warden who was an aspiring young writer before she died of complications from cancer. It looks simple. But it took me forever to draw. Every shadow and highlight was painstakingly plotted out with a computer mouse-operated “pen tool” in the Adobe Acrobat Illustrator program.