A good lifeguard is a dry lifeguard. Meaning: a good lifeguard is diligent in predicting and preventing trouble. I remembered this from my training days at Camp Scatico. Waking up on a Sunday, I had my cry, did my morning hike, loaded up the car for the week and took off for Strong Memorial. By the time I parked, I had morphed back into my Strong mode. Starting the week off on the right foot, I climbed the eight flights to the ICU, and was on guard again. Ready to meet trouble. I would handle anything Strong sent my way that week.

The Red Cross books on life-guarding and first aid list the first step when you arrive at the scene of an accident: “Survey the scene for danger.” I always got that. My skills in diving underwater and hauling frantic victims to shore were questionable but surveying for danger came instinctively. Always wary of what might lie behind a closed door, in a bag left on the road, at the bottom of a kitchen sink filled with murky water, or in an old takeout container abandoned in the fridge, I exercise caution. So on that Sunday afternoon, arriving back at the hospital, I knew immediately something was wrong.

First clue: Marika’s father and his wife were still there. They wore twin frowns. Marika had been taken off the ventilator earlier that morning, recovering after two unconscious weeks, and now the monitors sat silent and still. I quickly pushed through to her bedside.

“Hi Mom,” she said in a voice higher than I expected. She smiled joyfully at me.

“Hi. Are you okay, Mareek?” I asked, my own voice rising in pitch to meet hers.

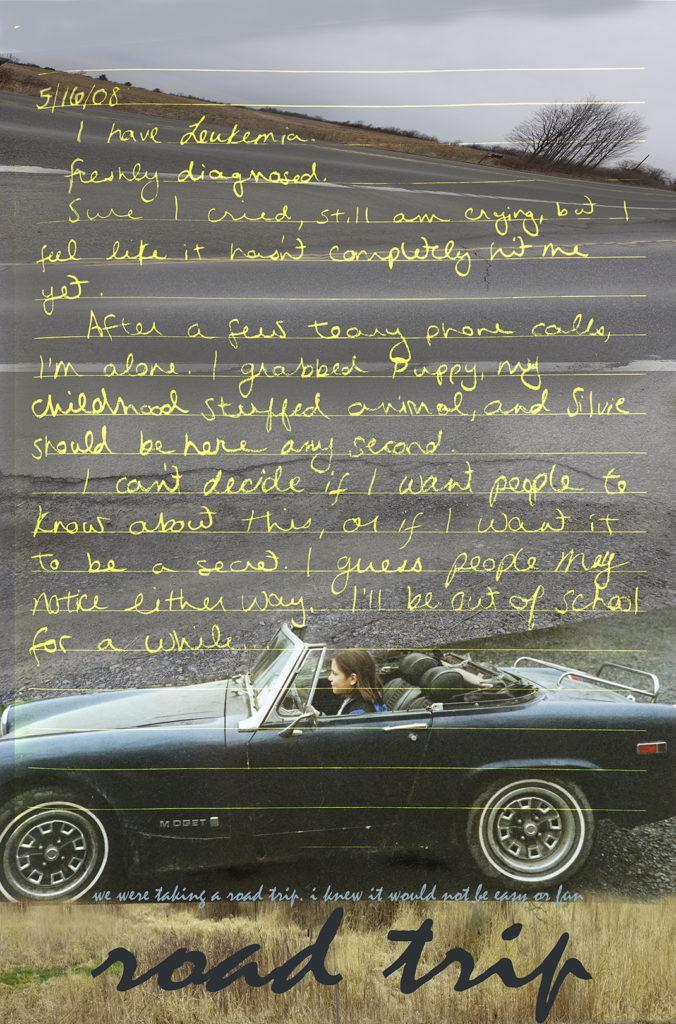

“Puppy.” She said, holding up her stuffed animal. I looked back and forth from Marika to Puppy to Marika again, to size up the scene: my Marika smiling at me, waving Puppy. Smiling. At me.

“Hi Puppy, it’s good to see you again.” I shook Puppy’s threadbare paw. Marika eyed me expectantly as I continued making a mental snapshot of things. Skirting familiar territory, in my special education teacher voice I asked, “Umm, can you count to ten, Mareek?” The situation was strange only because it was my own daughter I was assessing. Off on the side, her father was holding his head.

“Okay,” Marika said eagerly. “Okay. One, two. Three. Mom, Puppy.” She shoved Puppy at me like when she was three years old and wanted me to make Puppy dance. Baby Marika. Yow. What was happening? My little girl was back. And she liked to say “okay.” And now she wanted to sing. So we sang.

Surprisingly, Marika could remember many of the words to past camp songs and from beloved Broadway musicals. She now had me working hard to remember the words to Joni Mitchell’s “Circle Game.”

“An’ go around an’ round an’ round an’ round,” she was stuck like a broken record until I finally changed the tune.

“Oh the sun will come out,” I began an old favorite song by Charles Strouse and Martin Charnin from the musical, Annie, and she joined in. “Tomorrow. Betcha bottom dollar there’s no sorrow, come what may.” I held Puppy up and she watched, totally engaged. “Just thinkin’ about, tomorrow…”

“Keep her singing. It’s improving her breathing,” said Robert, the nurse who was adjusting the monitors next to us.

“Lah la la-la … hang on ‘til tomorrow,” we sang.

“Keep it up,” Robert encouraged, “It’s definitely helping.” Marika and I continued, both struggling to remember the words.

“La la-la-la something—something—sorrow,” we sputtered and came to a stop. And suddenly a deep baritone voice resounded around us,

“When I’m stuck with a daaaaay that’s gray and lonely, I just stick out my chin and grin and saaaaay—Oh—,” Robert sang with gusto, with hand gestures. We picked up our cue.

“The sun’ll come out tomorrow, so ya gotta hang on ‘til tomorrow,” the three of us sang loudly. “Tomorrow, tomorrow, I love ya, tomorrow! You’re only a day a-way!”

“Bravo!” I cheered, and turned to Robert. “You’re brilliant. You know all the words.”

“You wanna know how many school musicals I sang in?” Robert said. “I know all the words to everything. But I think we have to stop singing now. It seems to have increased her heart rate.”

I assumed Marika was just dopey from the lingering sedation, and that she’d come around shortly. But by Tuesday the Roc Docs were conducting tests to determine the cause of her change in mental status. Laurie was on the phone, upset because the doctors wouldn’t return her calls.

“I’m not used to being an obnoxious, interfering relative, but if that’s what I have to be, I’ll do it. I’ve had a few patients die in the past twenty-nine years, and I can’t help but wonder whether the outcome would have been different had I spoken up and made the specialists listen to me,” she said. “I don’t ever want to feel that way about Marika.”

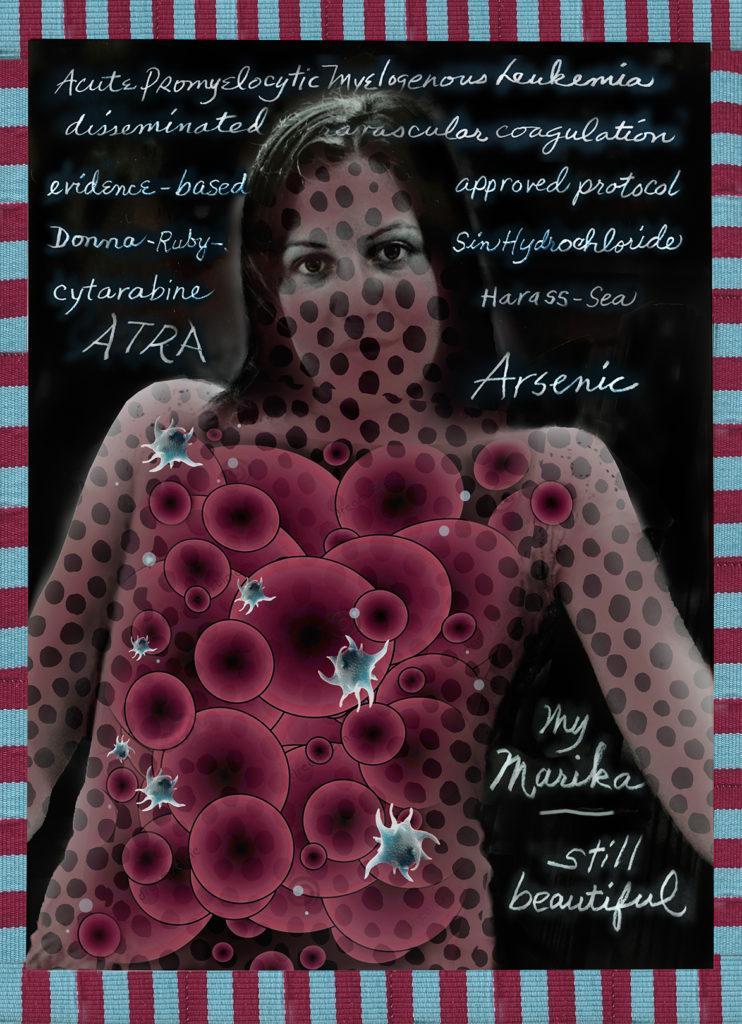

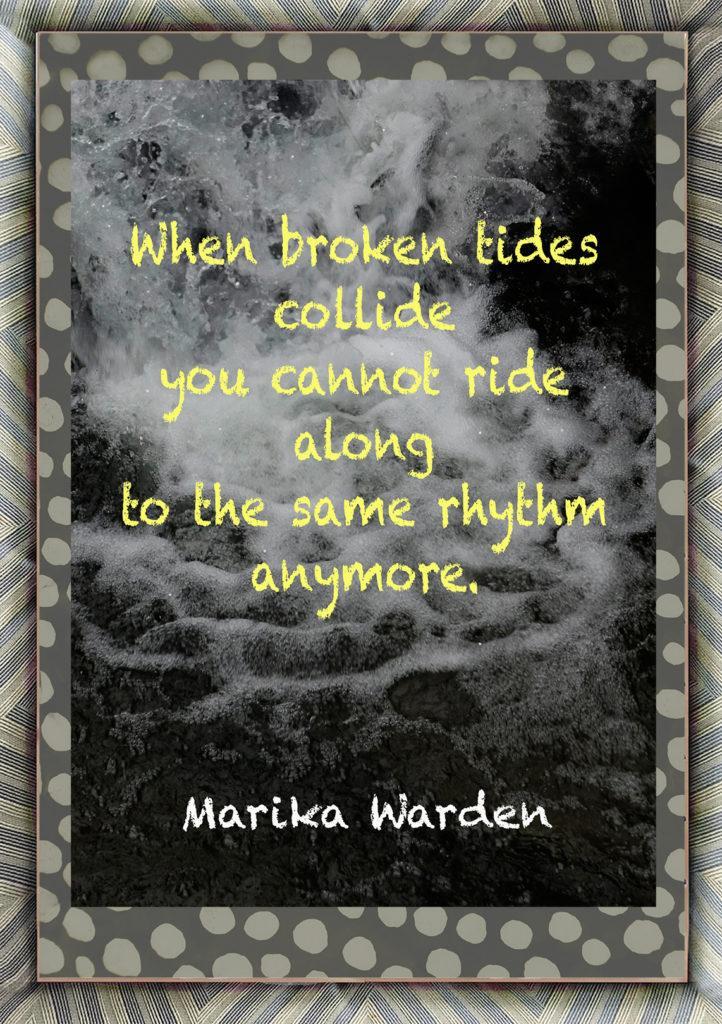

I’d forgotten one small detail in reporting back to Laurie. The doctors wouldn’t speak to her because Marika had arrived at the hospital this time with her friend instead of me, so the forms listing who should be privy to her medical information didn’t have Laurie’s name added. And now there was intense bleeding, nosebleeds so severe they made Marika’s blood pressure drop dangerously low. The doctors put us on alert. The Red Cross called Greg back from Afghanistan to be with his sister. Diagnoses and hypotheses showered down around us. But I was looking right into the eyes of my baby Marika who could barely see me, but was happy to have me there. And that night, after her father and his wife left, Marika’s breathing rate increased. Her oxygen level dropped and her heart rate shot off the charts. Afraid she wouldn’t be able to sustain the effort she was putting out just to breathe, the Roc Docs shoved the tube back down her throat and put her on the ventilator again.

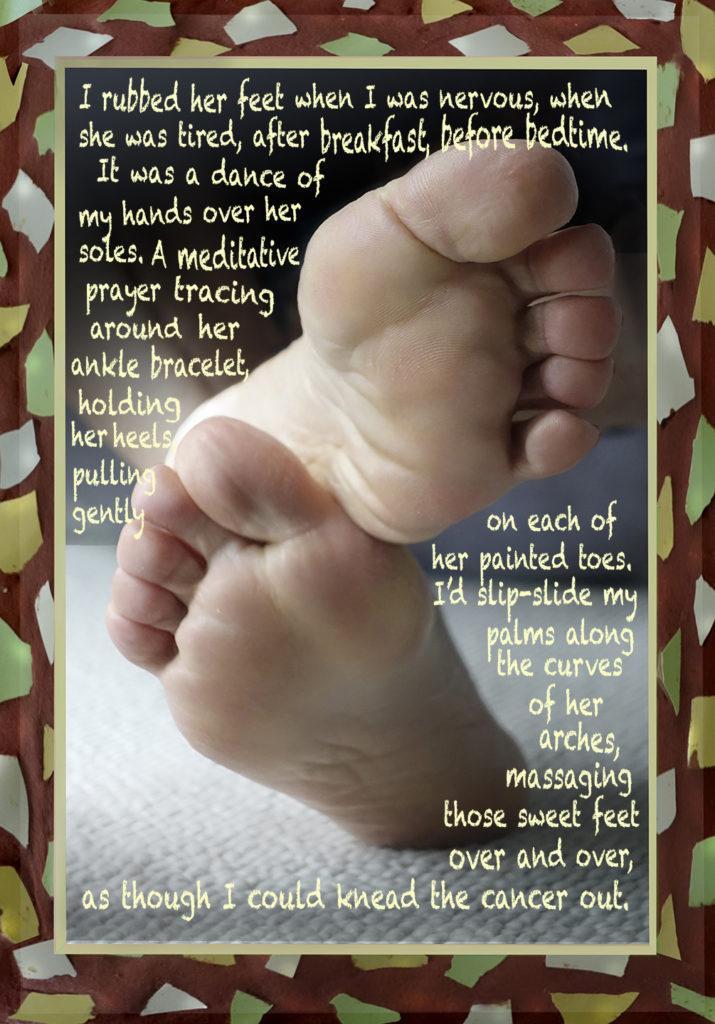

I rubbed her feet and lay low under the tent I imagined around us, sheltering us from the storm that dropped down in a tumult of medical terms. “Encephalopathy.” “Aspiration pneumonia.” “Chemical pneumonitis.” “Necrosis of the red blood cells.” And “leukemia cells in the spinal fluid.” They drifted beyond our small world where I alternately rubbed her feet and snuck around the tubes and trappings to come closer, to sing into her ear in a high choked whisper, “The sun’ll come out tomorrow, so ya gotta hang on ‘til tomorrow….”