If the muskrat digging holes in the banks of our pond were to continue to bore a tunnel clear through to the other side of the earth, it would end up in the Indian Ocean off the southwest coast of Australia. Marika had picked the farthest place one could go from our cozy home in the hills surrounding Ithaca. But on our first forays into the jungles of cancer, we were being carried off to a world even farther and more foreign, and there was no knowing what awaited us on the other side of it.

If the muskrat digging holes in the banks of our pond were to continue to bore a tunnel clear through to the other side of the earth, it would end up in the Indian Ocean off the southwest coast of Australia. Marika had picked the farthest place one could go from our cozy home in the hills surrounding Ithaca. But on our first forays into the jungles of cancer, we were being carried off to a world even farther and more foreign, and there was no knowing what awaited us on the other side of it.

To me, cancer was the demise of ancient neighbors, the terrifying realm of beloved grandparents. It wasn’t supposed to happen to one’s child. Although there was Marika’s father’s brother who died at age six, of a brain tumor, over forty years before. How could my daughter have cancer? All I could think was what did I do, or not do, to cause this? Visions of all the used and refilled water bottles in Marika’s room kept haunting me. Dozens of plastic bottles on the floor, in her gym-bag. In the hot car, festering toxins. “That can’t be good for you,” I’d mentioned to her, casually, way before cancer. What kind of mother was I that I hadn’t kept my daughter safe and healthy?

“Laur, you tell Mom. Okay?” I begged my sister, as cancer moved into our lives, clobbering me with guilt. And shame. I couldn’t face my own mother.

Everything Laurie read about Marika’s type of leukemia said that once identified, it should be handled as a medical emergency. By the time it was diagnosed, Marika’s disease was already advanced. Aggressive. So after one night in our local Cayuga Medical Center we dashed up north to Strong Memorial, a teaching hospital at the University of Rochester Medical School. But before she could escape the Ithaca hospital, Marika had to undergo the cancer novice’s initiation, the bedside bone marrow biopsy.

Marika lay prone in the hospital bed, waiting for the inevitable pain. We both saw the tool. It resembled the antique hand-crank drill I inherited from my grandfather, a carpenter in the 1930s. The doctor marked a spot inches above her tailbone. He braced himself. I held Marika’s shoulders down. He drilled. She shrieked. I cried, silently beseeching him to hurry up. Her face and neck turned red. I focused on the tiny waterfall that scaled her cheek and trickled off the tip of her nose, creating a wet blotch on the sheet. I wondered how they knew I wouldn’t faint. It was taking forever. And when the longest ten minutes of our lives were over, and after the required twenty minutes to stay very still ended, Marika grabbed the nearest thing, a box of tissues, and threw it forcefully at the wall where the doctor had stood.

So by the time we got to Strong Memorial and met that week’s squad of the always-rotating oncology team, Marika was already wary of doctors. Laurie called them the Roc Docs.

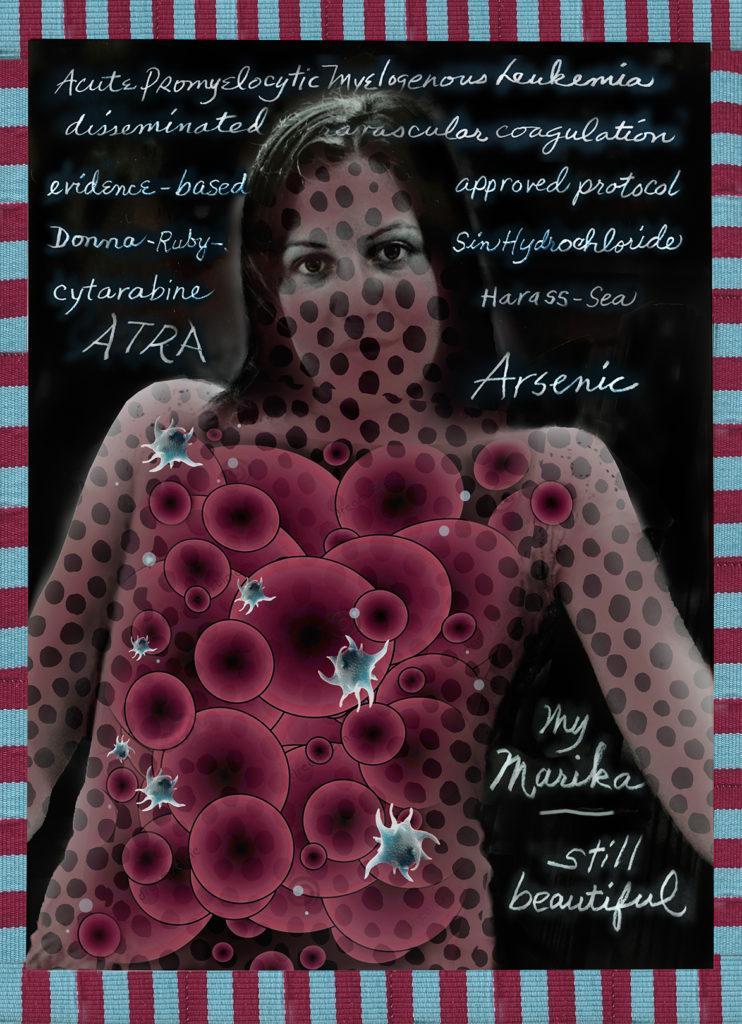

“Acute promyelocytic myelogenous leukemia, or APML, has an average survival rate of eighty-five percent,” they said, “depending on complications.” They wasted no time starting an intense chemotherapy attack. Three days later Marika developed her first serious complication. “Disseminated intravascular coagulation. DIC,” the Roc Docs reported. Marika’s blood clotted inside her blood vessels but she bled from everywhere else—every orifice on her body, through every sore, through the tender spot near her tailbone, under the retinas of her eyes, and into her lungs. Always squeamish around blood, I anxiously waited for the nurses to come back with more pads as I applied pressure through soaked gauze on one of her arms. Marika cursed through a towel she held to her nose and mouth. Leaning over to push the call button, I noticed she was lying in a puddle of blood. I did not pass out. An animated movie was playing in my head. It starred my headstrong daughter’s bone marrow that had produced lots of immature unruly cells that didn’t do what they were supposed to. Like those red cells that need to carry the oxygen, and the white cells which should be fighting infections. And her impossibly undisciplined platelets that were supposed to be clotting and stopping all this bleeding. I imagined millions of tiny-legged rebellious cells sneering, careening and carousing throughout every inch of her body. And I was thinking, Marika’s a rebel—clear to the core.

In the non-patient bathroom by the elevators, regarding myself in the mirror as I washed my hands, I saw old tired eyes. My nose usually bullied other facial features for attention, but now, small shuttered eyes glared back at me in cold detachment. I sighed and turned away from the ghostly reflection. Marika had gotten all the good looks in the family. Even sick and strung out by cancer, she still looked beautiful.

It was a showdown: headstrong Marika versus aggressive cancer. The Roc Docs pumped drugs with strange names through her. Daunorubicin Hydrochloride, Cytarabine, something called ATRA that sounded like a sneeze, and something I heard as “Harass-Sea.” There were established formulas for treating this leukemia. Complying with these evidence-based approved protocols was considered the path to beating cancer. In my head the medicines blossomed into yet more cartoon characters, like Sigh-terror-bean, Cytarabine. Donna-Ruby-Sin Hydrochloride. Reactions to these chemo cocktails could be deadly. And when the ATRA almost destroyed Marika but failed to put her into remission, they gave her arsenic instead. That one I knew. In my head I saw the dead shriveled-up mouse I’d found as a kid, on top of the mail pile. “Arsenic,” my Mom had frowned at the mouse, explaining, “I forgot to leave a holiday tip for the mailman.”

Marika had horrific reactions to everything. She retched, and wrenched in pain. I winced as she threw a cupful of pills down her throat with a fast splash of water.

“How do you do that?” I asked, remembering smashing tiny aspirins in applesauce for her just a week before. She shot me a look like I had food on my face.

“Mom. I’m a cancer patient.”

“Pretend you’re trees. Open your arms wide like branches reaching out,” I said to the tiny group of people posing before my camera. They stood there, smiling at me, with outstretched arms. We were gathered for the first meeting of The Compassionate Friends of Ithaca, New York, a child loss support group. “Look up at the sky,” I directed, thinking they looked like children waving in the wind.

“Pretend you’re trees. Open your arms wide like branches reaching out,” I said to the tiny group of people posing before my camera. They stood there, smiling at me, with outstretched arms. We were gathered for the first meeting of The Compassionate Friends of Ithaca, New York, a child loss support group. “Look up at the sky,” I directed, thinking they looked like children waving in the wind.