Remember how I warned you—my story bounces around a lot? This will be a bumpy ride. You will be jerked back and forth between times and places. Like now—before I continue with my journey in Australia, let me drag you back to the fall of 2010. Mainly because my heart is always being dragged back there, to the edge of a bottomless pit of regrets.

Autumn is one of my least favorite times. I don’t like to see summer die. Flowers shriveling up, leaves dropping, the woods turning colorless and cold … all followed by the long Upstate New York winter. Just thinking about the upcoming winter totally dims the richness of harvest time and the changing colors of the hills.

Marika, as always in September, was focused on what she would wear for Halloween. In remission, and on medical deferment from Ithaca College for a second year, Marika was taking two music courses at Tompkins Cortland Community College. She was singing again, writing and recording with her music partner, Russ. She and her friends had abandoned the old Limbo in Collegetown for a fresher, tidier apartment with a yard and parking area. Marika’s nights at the new Limbo with the old friends were livelier than ever. They could make Halloween last two whole months.

“On Wednesday, we have to leave for Rochester at seven-thirty in the morning. Do you want a wake-up call?” I asked as we drove back to her apartment after the Monday blood draw.

“So early?” she complained. She resented these trips. But I was excited. At any time, the Roc Docs could announce that a transplant donor had been found.

Two days later, picking Marika up at Limbo, I knocked lightly on her bedroom door,

“Mareek, are you ready?” There was a sudden scrambling on the other side.

“I’ll be right down,” she said, flustered, as she stumbled past me to the bathroom. “I’ll be in the car in five minutes,” she yelled from the toilet, my cue to go wait in the car. Someone was still scuffling around in her room, so I went downstairs to the car, wondering if there was a new boyfriend. I would be the last to know; she rarely shared anything about her love life. What kind of time was this to have a boyfriend anyway? Now that she had cancer my own life was all but halted. How did she get to have … A sudden loud clunk outside the car, Marika was gesturing sharply to unlock the door.

“Next time, I’m going up with a friend,” Marika said, like it was my fault she’d overslept. She threw herself into the back seat, slammed the door, and plugged her ears with the iPod earbuds. The ride to Rochester was long and silent. Who was the guy? I wondered. Much later, Rachel told me about Marika’s Australian boyfriend.

“Oh, the people, the parties, the bonfires, the laughing and drinking,” Rachel said, “all the time. Marika and Pat were so sweet together. She sang. He played the guitar. He told her stories.” Much later, I would find what Marika wrote about her first days with the Australian.

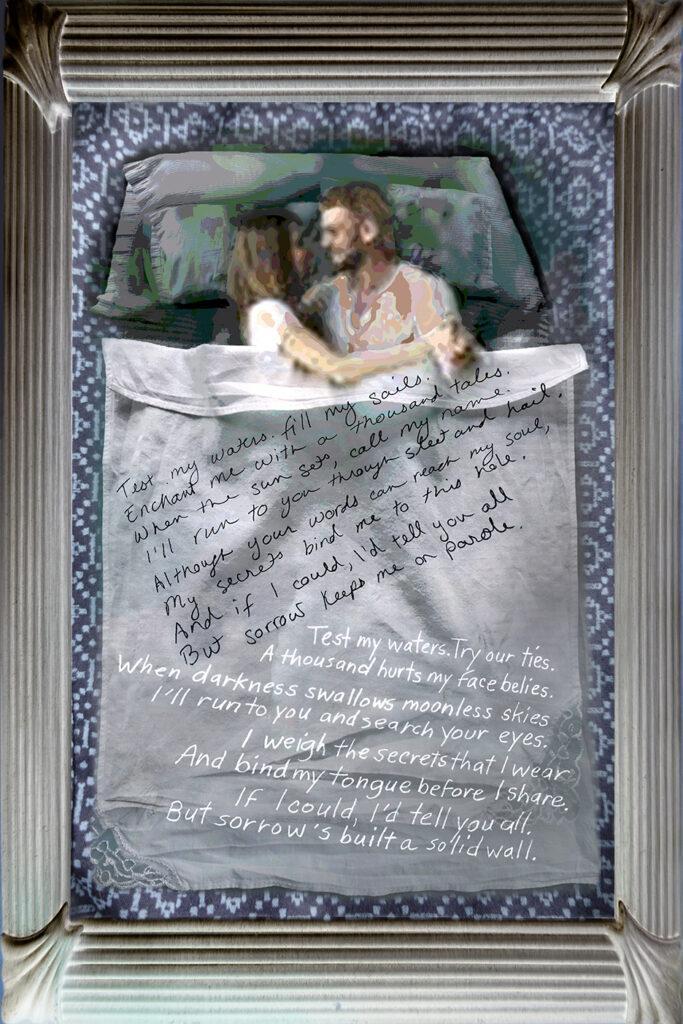

Marika on September 29, 2010:

It was a perfect autumn evening. A gray haze of clouds hung overhead and we just sat outside enjoying every breath, every minute of it. He strummed the guitar lazily while I sat in the grass humming to myself.

Inside we go. Fiddling around with the computer proved futile, and out of “exhaustion” we collapse onto the bed.

I cannot tell him. Not yet. My dream can’t be over yet.

I begin to feel my eyes shut and hear a silent laugh escape his lips out of amusement at my drowsiness.

When I open my eyes I pray he will be looking, but his eyes are closed. I sigh and drift off again a little.

Bits of chatter season the moment.

This is tag. Who will make the first move?

I shy away from the opportunity.

“What are you doing?” I ask myself. “You are leaving soon. He is leaving soon. None of this!”

I fight the butterflies in my stomach every time he moves.

Why do the best dreams always end so quickly?

After neither of us can stall any longer we rise and leave.

I will see him again. Night will come and I will dream again.

The next week goes by slowly. “Opportunity is not a lengthy visitor,” and I certainly missed my chance. I vow to myself that I will not forsake my next opportunity with him.

My next opportunity comes quickly.

We are sitting on my couch, surrounded by my friends. He is playing with my hair.

How I miss my hair.

We move upstairs. I know I should seize the moment, but he doesn’t know my secret. How could he know? He has not yet seen the scars that adorn my chest, or the surplus of medicine bottles in my dresser. He has not read the words in my journal, the doctors appointments on my calendar. Do I give myself to someone who knows not what baggage I carry? Do I tell him? I love that he doesn’t know. I love that he treats me as if I am healthy, normal.

Before I know it, it is too late. Our clothes litter the floor as we dance underneath the sheets of my bed.

I wake early. His eyes are closed. My hand instinctively rubs the scar on my collarbone as I wonder if he knows I am not quite right.

Once he awakens, we head downstairs. He is ready to leave when he asks. He asks the question that I dreaded the whole night. He inquires about my scars. My mind races. Do I lie? Do I risk him running away, or do I give him something else to mull over? I decide that honesty is the best route and I tell him about my scars. I tell him about my cancer.

Suddenly, he doesn’t have to leave. He stays for three more hours. We talk. We lie out in the sun and I listen to his wonderful stories. I try to remember as many stories as I can, knowing that soon I will be alone in hospital with nothing but memories to keep me alive. I try to remember everything: his voice, his kiss, his eyes…

I turn to memories. I turn to happy days. I can’t rewind. Instead my mind replays.

“Opportunity is not a lengthy visitor,” Marika quoted from the musical, Into the Woods, by Stephen Sondheim. It was her mantra in the fall of 2010 as she partied, stocking up on memories. Laurie and I berated her for being in denial. We were supposed to have the transplant now that she was in remission. And who knew how long this remission would last? We were in a race against time, against the incorrigible demon, cancer. Laurie printed out the bleak statistics on survival rates for transplants, and I couldn’t eat or sleep. But Marika—she wouldn’t even look at the pages. Marika was in love.