Long Island, New York. I knew nothing about how to navigate my way around the place of my birth. Yet every cell in my body was acutely aware I was back home. My original home. Where Marika was immediately accepted into the drug trial program at North Shore Medical Center. Insurance was going to pay for it so we were going to be stuck on Long Island for most of the summer. I followed the GPS instructions to my cousin Norm’s apartment in Woodbury, twenty minutes away. Norm was graciously giving us his guest room and the living room couch for our first weeks in treatment. We unloaded Marika’s belongings into the guest room before she took off with Rachel. I got the couch.

The girls spent as much time together as they could between Marika’s appointments and Rachel’s classes. Some days Rachel took Marika to Jones Beach, my old hangout. They wore eye make-up and dressed in little bikinis. Marika’s tiny cutoffs sat well below her navel ring. Joined by friends, they wave-surfed and picnicked with wine coolers, beer, and watermelon. They stayed up late, stargazing in Hofstra’s intramural fields where Marika sang long into the night with strangers who brought guitars. They laughed, made up lyrics, and ducked in the gully to avoid the patrolling public safety enforcers. Marika went with Rachel’s friends to a concert in Brooklyn where the tickets were sold out so they climbed over a fence to watch for free. They rollicked all over Long Island while I lay low, reading in Norm’s apartment where it was cool and quiet. Except for a noisy air conditioner. Which I kept off as much as I could stand, not wanting to hike up Norm’s electric bill. When temperatures fell below eighty, I ventured out to hike along Jericho Turnpike. It was harrowing to walk alongside moving vehicles, but I felt oddly alive being whipped by the hot blasts of their passing. I couldn’t simply sit inside all the time. Sometimes I just needed to be out under the sky, to have room to stretch.

The GPS was set to find the medical center, west of Norm’s. It was set to find Rachel at Hofstra, somewhere east. “Have GPS will travel” was my motto. When Marika went out with Rachel, I sometimes took off to find Turkish restaurants, shopping sites, and parks to walk around. Anywhere I could get an address to plug into my GPS. But on one hot afternoon, driving Marika to Rachel’s, we noticed the GPS was dying. First, the feisty female voice quit. Lindsay Lohan with barely restrained attitude stopped ordering me around, stopped badgering me, sneering, “Ree-lo-cating,” like she had to work hard not to add, “dumb bitch, you missed this turn for the fifth time.” If she had eyes, she’d have rolled them like Marika. She ditched me.

Then the map disappeared. By the time I dropped Marika off, the text of instructions had gone entirely as well. I felt abandoned. Terrified, I tried to retrace my way back to Norm’s, but I was lost. I drove on, searching desperately for something familiar. I was in a sea of highways. Wide bands of roads crammed with cars crisscrossed, curled, and tangled over and under in churning waves. Directionless, I wiped my sweaty forehead, and continued with the flow of traffic until an exit advertised a shopping mall. I turned anxiously from the highway, my first intentional move on Long Island without the guidance of a global positioning system, and found the mall’s Best Buy. A half hour later, with the new Garmin Nuvi GPS set to a charming British male voice, I was back on the road again.

Almost every town I passed on Long Island had a memory tucked away: an old boyfriend who lived in Wantagh, a factory my father once owned in Westbury, the parking lot at Roosevelt Field where our family dog died when a friend left it in a hot car. Most haunting about being back though, was the ocean. It was in the air all around me, always just beyond the crowded highways and stretches of shopping centers. It was in my blood. To be on Long Island in the summer was to feel the Atlantic Ocean and the Long Island Sound pulsing in every part of me.

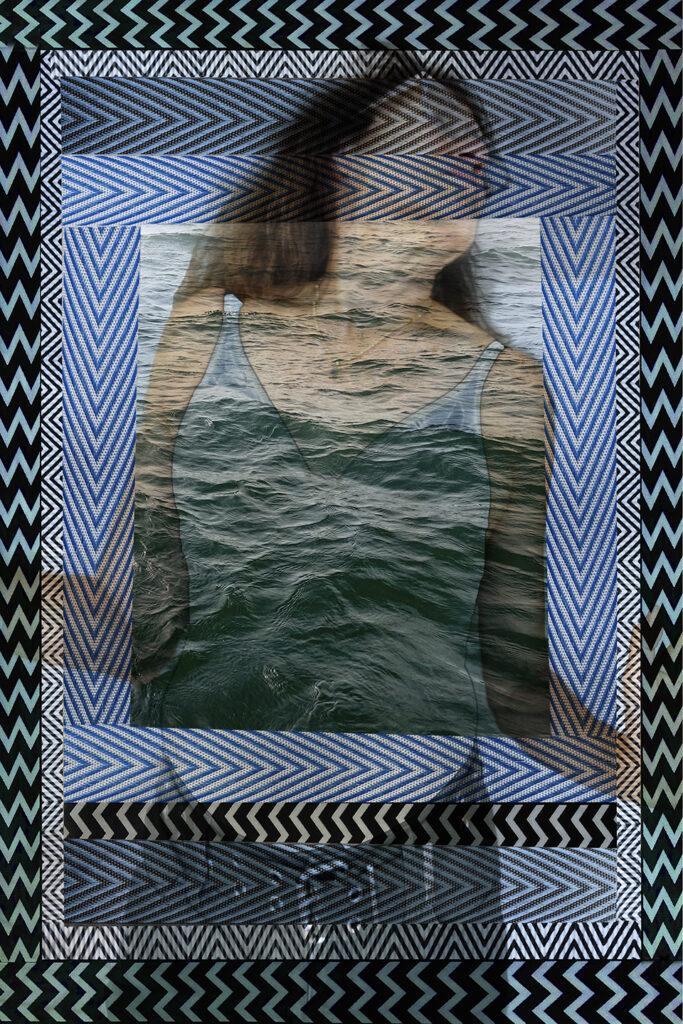

Living in Ithaca, I missed the ocean. So we’d take vacations to beaches, with boogey boards and picnics. My children were fearless in the water, maybe because I’d swung them around in Cayuga Lake and in pools and ponds from early on. But I was always terrified of waves. If I went into the sea, I stood stiffly in the waves, jumping up as high as I could at each swell, keeping the kids close, ready to grab before they could be pulled under. Because as a young girl, one summer on Jones Beach, I was swept away by a wave. Not very far. But I remember being petrified, helpless under the water. The sea was way stronger than I. It was vast and violent below its surface. And it wanted to swallow me. Crying, I finally pulled myself up out of the shallow remains of the wave and looked about. I could not find my mother whose hand I’d been holding only a moment before. Salt water stung my nose and throat. All around, concerned strangers reached out to help me. But I was not supposed to talk to strangers. I was frantic. Lost. Battered by the ocean I’d loved. And where was my mother?

That trauma haunted my dreams. It gave me a tremendous respect for water. It made becoming a lifeguard the hardest thing I ever tried. And it fired a small current in me every time I watched my children in the waves. In no way could I stand the thought of Marika or her brother being lost or scared like that. In pain. In any sort of trouble, with no mother to protect them. Back on Long Island during the summer of 2010, I visited the ocean at Jones Beach only once. I didn’t have to see it more than that. It was in me.