My story bounces around a lot. Back and forth between times. That’s because I, myself, am always straddling time, living with one foot firmly planted in the past and the other limping in the here-and-now. Time is so squirrely. It’s always getting waylaid by something catastrophic or miraculous, or just plain draining.

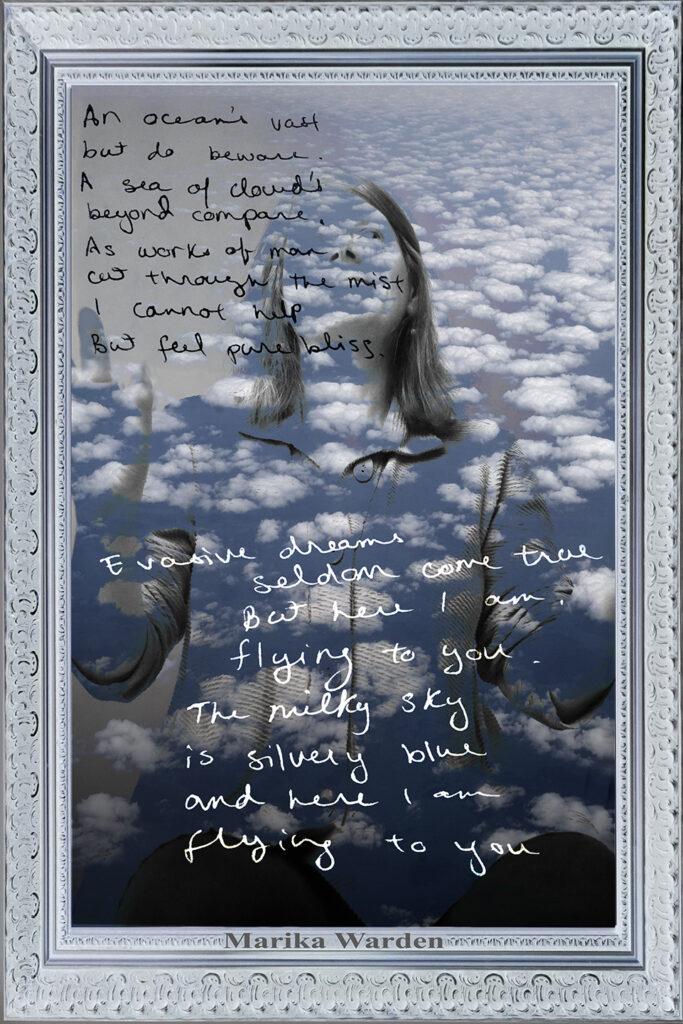

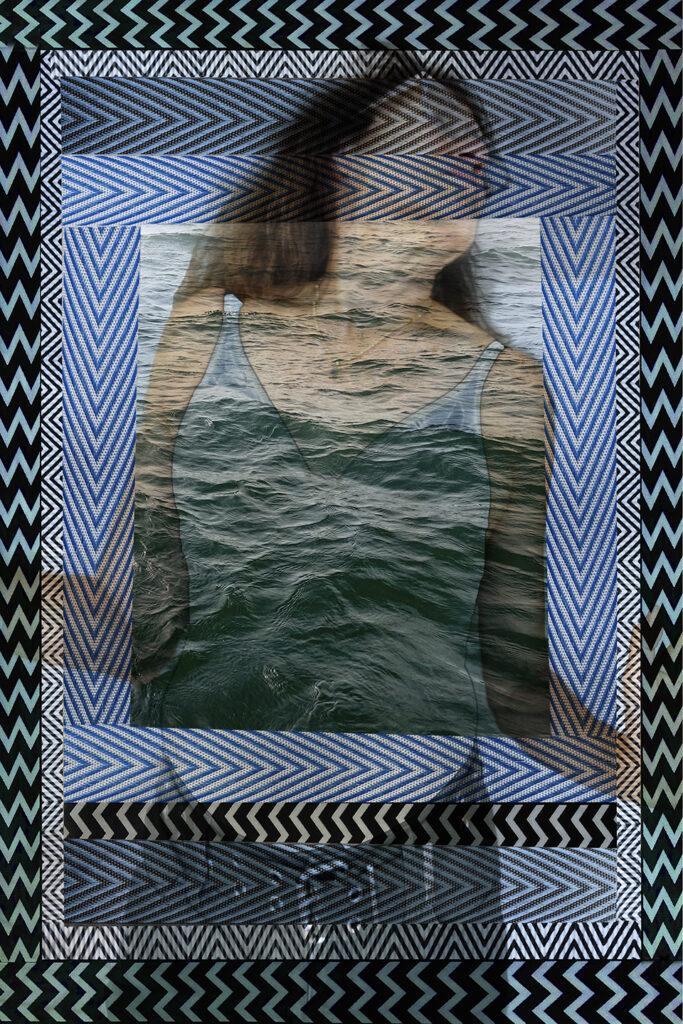

What am I doing? I ask myself when almost everything I do is for Marika. In the spring of 2012, I’m going to Australia to carry out her last wishes. The trip is an extravagance I would never have allowed myself. But someone was going to have to go someday, unless we would have brazenly mailed her ashes off to that Australian she loved, who never answered my emails, and let him dispose of her ashes, easy and cheap. No. In April 2012, I am still standing guard over her. Her ashes. This is part of our journey together. And for me, a journey is never simply a distance covered in time or space. It’s an opportunity to change something. It can be open-ended, intuitive, or steeped in purpose, but a journey is dependent on attitude more than intentions. Where will I allow myself to go? Can I stay open to whatever comes my way? And if something goes wrong, if “broken tides collide” like Marika wrote, will I be able to smile—one day, if not immediately—and accept that it was simply what happened? Just part of where that journey would intercept another path?

Australia was Marika’s dream for another shot at life, a life without cancer. And when my journey is over I, too, will start a new life. My life without her.

I have to keep reminding myself I will not find Marika in Australia. Not a trace of her. She was there only two weeks. When she left home, I gave her tickets and a Triple-A Travelcard loaded with three hundred dollars. I told her not to spend money on anything for me. I just wanted to know about different foods she would find. And she gave me, on her return, cookies and a postcard with a cheeky four-year-old in a superhero costume on the front. It was a government-issued advertisement for product safety she’d gotten for free.

“Mom,” she had written on the back of the card, “Always Marika, Top 5 foods from Australia to try: 1. Vegimite!! – Very salty 2. TimTams – Especially dark 3. Rosy Apple Bits – ask me for some 4. Australian style bacon – probably can’t find in US 5. Lamington slice – I couldn’t find. I need to try too!” Right there was an unfinished mission, I noted.

Then there’s her scrapbook with clippings, postcards, and brochures. And photos. Photos Laurie and I googled to match the backgrounds with images of particular places. So I could have an idea of where Marika’s feet had taken her, “which way my feet are going,” like Marika said.

She had flown to Australia alone to meet up with her lifelong friend from Ithaca, Carla, who was at school in Sydney for the year. Marika had other friends there as well. I will have no one. She’d asked for extra money to rent a car and I’d said no. So I will not allow myself to have a car there either. I will not open the box to spread her ashes until after Sydney, after one last flight five days later to Melbourne. I’ll take four full days in Sydney to calm my apprehensions, fuel my courage. I’d planned as much as I could before the trip so I wouldn’t end up immobilized by fear in hotel rooms for the whole two week trip. Yes, I’m terrified. That is why, on my last night home, I emailed twenty-two women, my Australia-Alone Support Squad:

If you’re getting this email it is because I regard you as someone who has been strong and supportive, and I need your help now. I am on my way to Australia with Marika’s ashes. But I am not alone. I have her stuffed Puppy, my iPad, and you. It is scary but I can do this …

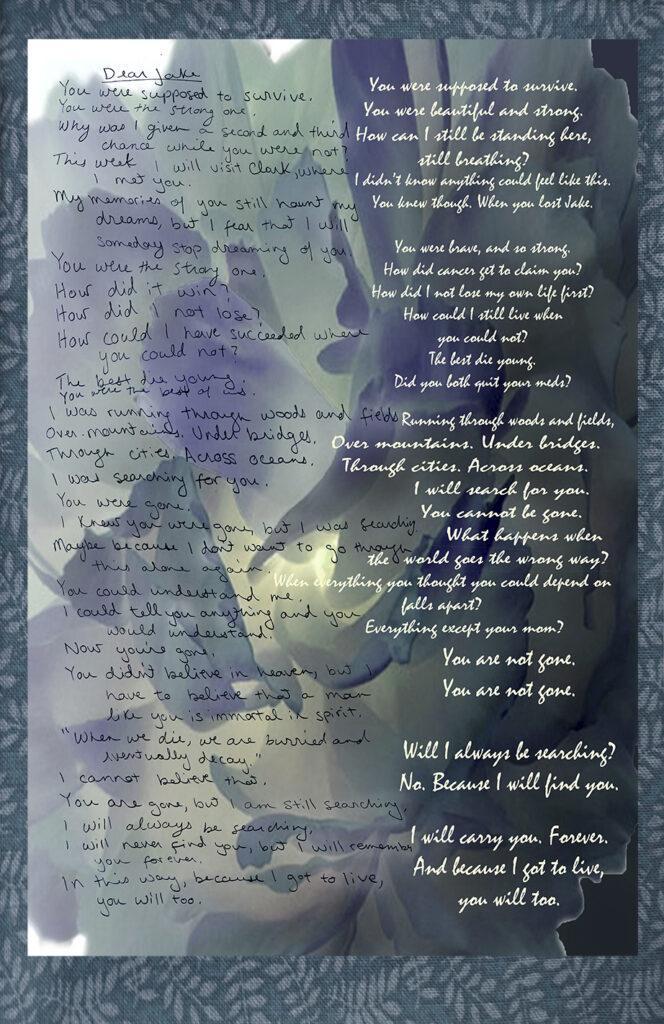

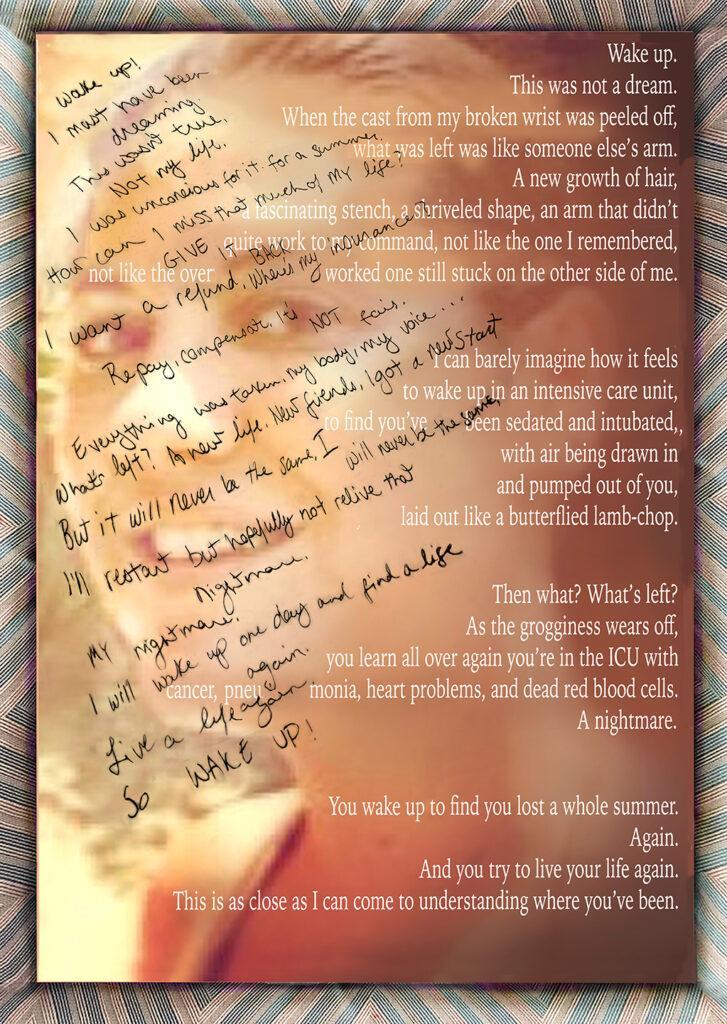

To Marika I wrote, in response to her poem: Marika, I am not “Flying to You.” There will be no one and nothing to greet me. I will arrive alone, tired and hungry, and scared because I will have to fend for myself as soon as the plane lands. I will not be rewarded with your smile or anyone’s open arms. Oh, to be flying to someone I love. And now, over this past year of grieving, I have found all your words, all over the house. There won’t be any more poems left to find when I get home. But while I was packing, I came across a framed drawing of a rabbit you’d made that said “Welcome Home Mom.” I put it on the mantle outside my bedroom, to be the first thing that greets me when I return from Australia.

Let the royal rumpus begin, I always say upon starting an adventure. Buckle up. We’re gonna bounce around a lot.