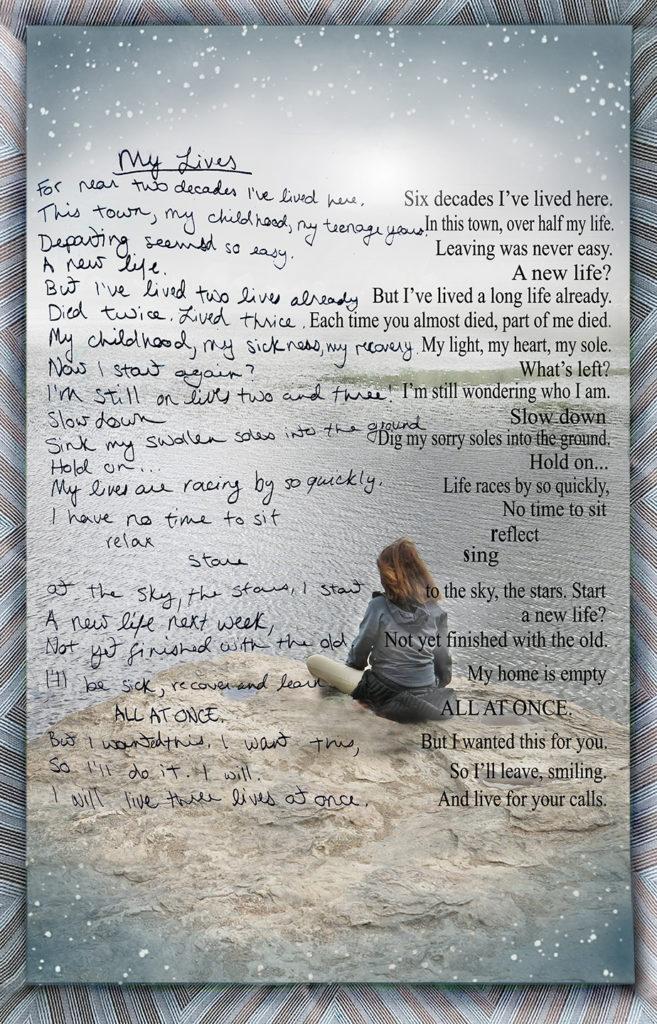

Sometimes I got my life mixed up with my daughter’s life. Like whenever Marika’s blood was drawn, I felt the pain. And once, in the ICU, I watched the monitor display her racing heartbeat for so long, I had to be taken downstairs to the emergency room as my own heart quickened and surged. Marika was getting the transplant, but I was getting a severe panic attack. As we waited for the transplant, I had to remind myself to relax. To breathe.

Late in the afternoon on December 1, 2010, the Roc Docs entered our room looking defeated. I worried, maybe something had happened to our donor. Doc Phillips was back, heading the team. But he did not look like his jolly old self. He sat down heavily and began with a long sigh.

“You are no longer in remission,” he said to Marika. Remembering how we’d postponed the transplant for her concert, I couldn’t bear to look at her.

“So there’s no transplant?” I heard a small voice say. Was it mine? Or Marika’s?

“Things have changed. We do have some good news out of all of this. We have a silver lining,” he said, recovering some of his cheer. “A silver lining,” he repeated. We waited, shaken. “The presence of leukemic cells makes you ineligible for the donor transplant. But,” he said with a dramatic pause. “But, remember that collection of stem cells we harvested from you last March, after the arsenic treatments?”

“Yeah. And then I got leukemia again three months later,” Marika wailed.

“Well, the new plan is to give you an autologous transplant using those cells, your own harvested cells, in the next day or two. This won’t cure you, since you had leukemic cells shortly after the harvesting, but it can get you back into remission briefly. And then you can have the donor’s-cells transplant.” I hugged myself and wondered how many more months until we were on the way to being cured. Relapse number three, and it wasn’t even summer yet.

The autologous transplant was a quick, uneventful procedure, so at the end of the week I went home to Ithaca. When I returned on Sunday, an electronic piano had been moved into the hospital room. New posters were taped onto the wall opposite the bed. The place had a cozy, lived-in feeling, a look that smacked of exuberant festivities.

“How was your weekend?” I asked, trying not to sound overly nosy.

“Mouth sores,” she said gloomily, reminding me of Eeyore from Winnie the Pooh.

“Oh, I brought you Vitamin Water. Maybe that will help.” I unpacked food items, fresh laundry, and mail. Gift bags and an assortment of drinks from her father and his wife already lined the windowsill. A big shiny balloon sailed above the end of the bed, which meant Rachel had been there. I rarely saw Rachel anymore as she worked weekdays. She must have brought the half-eaten chocolate cake that sat on the bed-tray too. They’d had a big party here all weekend, and I got to come back to Eeyore.

“Can’t talk,” Marika said sullenly.

“That’s not good. Are they giving you lozenges or something?” I asked.

“Can’t swallow,” she said, grabbing the croissant I’d placed on her tray.

In the next few days her cell counts rose to acceptable levels and we went home for the holidays. Our donor, the complete stranger who was going to share his blood, rich with stem cells, so Marika could live, would wait for us. Again. For the end of January. I wrote and rewrote a thank you letter to him that the Roc Docs would deliver. The holidays sped by quickly. I celebrated everything I could. Chanukah, Christmas, Kwanzaa, the Winter Solstice. I made tiramisu. Marika and Greg took me out to Bandwagon, a new Ithaca restaurant and brewery. He bought dinner. She gave me her new CD. I gave them each hundred dollar bills wrapped in new gloves, with Chapsticks and chocolates.

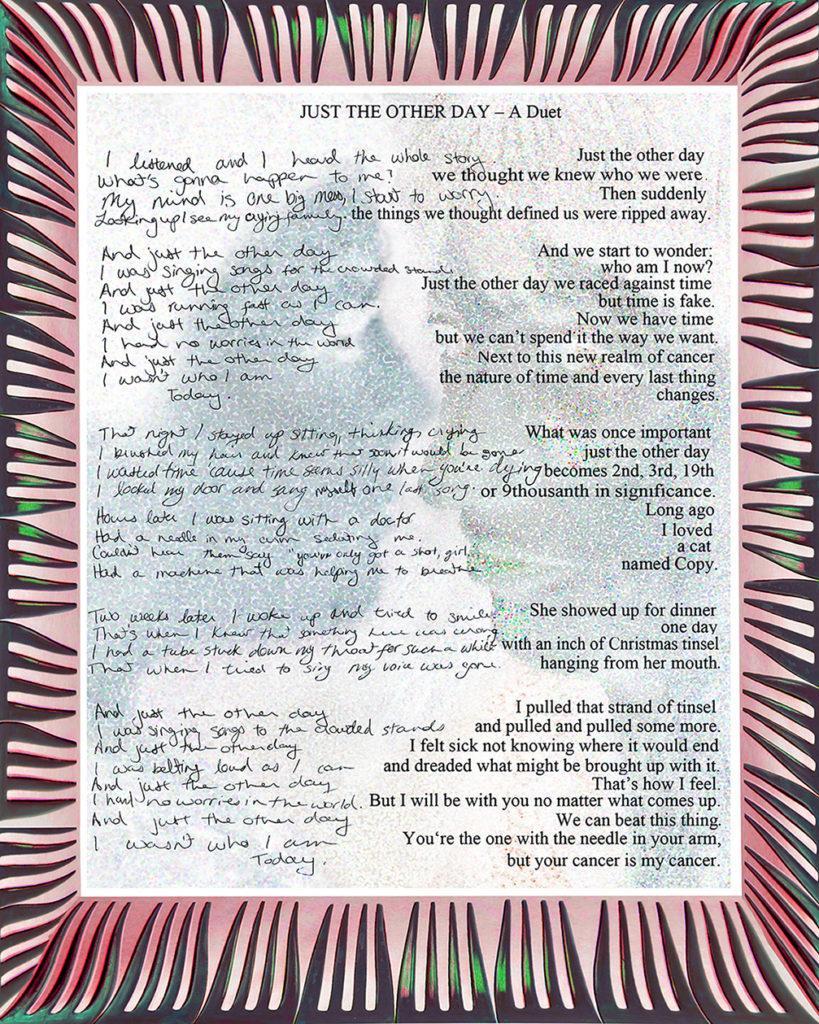

“It’s not finished yet. The CD. There’s another song to be added,” Marika said. She sat across from me wearing a turquoise head wrap, large hoop earrings and eye make-up. She had a party planned for after dinner. Her friends were home from college, and she was cramming what she could into her nights. During the days she came home from Limbo to do laundry and sleep. She’d creep down the stairs every so often, “Mom, ‘s there anything to eat?” I loved that time before the donor transplant. It was peaceful. Quiet. Like the calm before a storm.

Deep, dirty snow mounded up along the roads in Rochester on the morning we arrived back at Strong for a full week of chemotherapy and radiation. I piled Marika’s belongings onto a stray wheelchair in the parking garage. My own things remained in the car to be unpacked later at Hope Lodge, the cancer families’ home away from home. I stashed away her bathrobe, slippers, and toiletries exactly where they were in the last room, and then, just as I pulled up a chair, Marika handed me a three-page typed document. Fumbling for my glasses, I saw it was a list of all the places in Rochester I could visit for free.

“You’re not staying,” she said firmly. “I don’t want you here all the time anymore.” For a few stunned seconds I stood there trying to collect myself.

“But your cancer is my cancer,” I whimpered.

“Mom. Get a life,” she blasted back. For a few more seconds I forgot to breathe.

“Okay, but I’ll be here every morning for the doctors’ rounds,” I said, “and then I’ll leave until dinnertime.” She loved her dinners. “And I’ll be on the treadmill in the family room for an hour after rounds each morning, if you need me—need something.” Despite my bruised feelings, I was gaining momentum. “Otherwise I’ll be at Hedonist Chocolates, Wegmans, The Owl House Café, or Dinosaur Barbecue,” I added, naming her favorite Rochester eateries, “or any of the places on this list.” The plan worked for two days, and then the effects of the radiation kicked in and things started to get scary. On the third day, after the morning rounds, she flashed me her pathetic puppy-face as I got ready to leave.

“Aren’t you gonna stay?” she begged.