I know how it is to lose a child. An almost-adult child I loved and had high hopes for, whose life my own life revolved around. She was, and still is, half my world. “Always,” she used to sign her letters. Now, she is “always” in my heart.

I know how it is to lose a child. An almost-adult child I loved and had high hopes for, whose life my own life revolved around. She was, and still is, half my world. “Always,” she used to sign her letters. Now, she is “always” in my heart.

I know how it is to worry about a son. To stay up beyond my bedtime, wondering when he’ll come home or if he’ll make it home. There are so many things that can happen to a young man these days. “Mom, seriously? You worry too much,” he says. But maybe he’ll run into a bad situation some late night. And what if my son, the other half of my world, were to get stopped by a policeman? Would he find help? Advice? A warning? A sympathetic ear? Or would he find trouble?

I do not know what it is like to be the mother of a young black man. In a country where every day so many young black lives are wiped out, the mother of a black man must surely pray her son will not find trouble, will not find himself in the presence of police. “Please let him be safe. Please. Let him come home.” Always. Night and day. Fear for the life of your child could strangle the life out of you.

Another day, another killing. Another brokenhearted mother. And just the thought of that mother’s world collapsing around her, the memory of what it was like to see my own daughter’s lifeless face, the knowledge that another mother will never again see the sweet eyes of the child who lit her life – makes my heart tremble and howl.

Thanks to fellow student Travis, for his smile, wherever he is these days. My regards to his mother.

Decades ago every event or holiday was an opportunity to dress my young children in colorful costumes. Our calendar was always full. Parties and picnics. School celebrations. Parades. Pleased with their new outfits, and anticipating the festivities, my kids posed, sometimes smiling, for the camera.

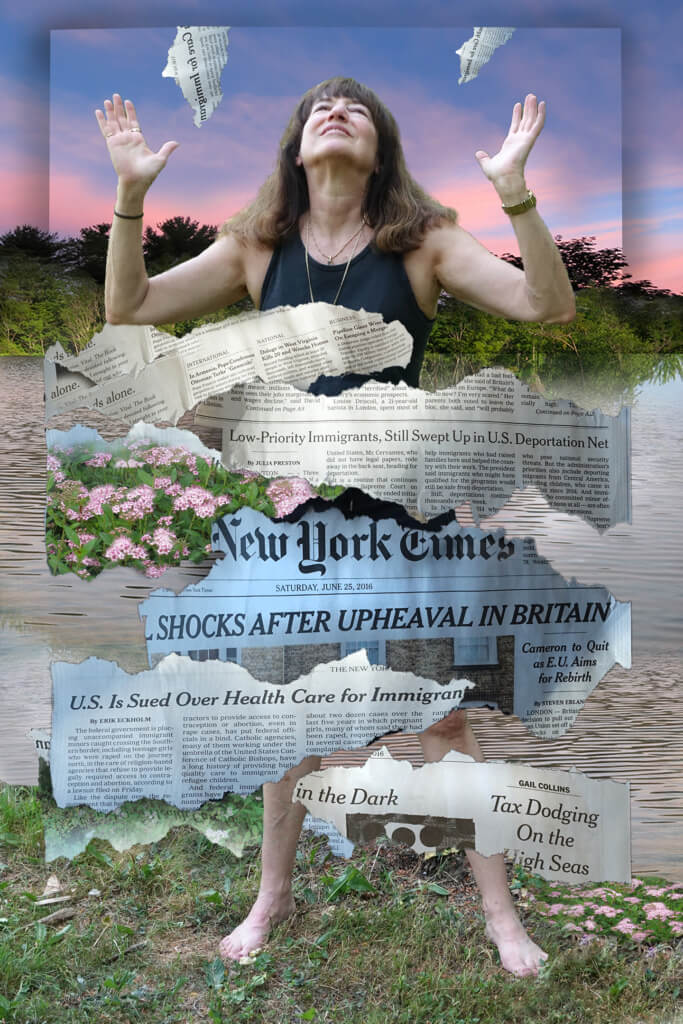

Decades ago every event or holiday was an opportunity to dress my young children in colorful costumes. Our calendar was always full. Parties and picnics. School celebrations. Parades. Pleased with their new outfits, and anticipating the festivities, my kids posed, sometimes smiling, for the camera. “I am not the same person I was before.” Another mother said this, as the setting sun seared the landscape behind her. Sitting on the edge of a deckchair, hunched over an almost-empty plate, I looked up suddenly. Sweet light danced on her hair, on the pond beyond her, in the gardens, and in the faces of the others around us, the ones whose old selves had been torn apart by tragedies that now brought us together.

“I am not the same person I was before.” Another mother said this, as the setting sun seared the landscape behind her. Sitting on the edge of a deckchair, hunched over an almost-empty plate, I looked up suddenly. Sweet light danced on her hair, on the pond beyond her, in the gardens, and in the faces of the others around us, the ones whose old selves had been torn apart by tragedies that now brought us together. “Lady, if you can’t control your brat, we’re gonna call the police,” the salesman in Ithaca’s old Dick’s Sporting Goods said. In the store’s stockroom that served as a makeshift dressing room, four-year-old Marika, in one of her monumental tantrums, was hurling helmets, cross-country skis, and whatever other merchandise she could reach.

“Lady, if you can’t control your brat, we’re gonna call the police,” the salesman in Ithaca’s old Dick’s Sporting Goods said. In the store’s stockroom that served as a makeshift dressing room, four-year-old Marika, in one of her monumental tantrums, was hurling helmets, cross-country skis, and whatever other merchandise she could reach. “You should write some final wishes. Just in case,” I’d told my daughter, like I was asking her to make a shopping list. It was back in November 2010, before her stem cell transplant. She was going to

“You should write some final wishes. Just in case,” I’d told my daughter, like I was asking her to make a shopping list. It was back in November 2010, before her stem cell transplant. She was going to