In Melbourne, right away I regret not leaving more time to experience the city Marika’s friend Carla told me Marika really loved. Immediately after arranging the altar in the new hotel room, I take the free two-hour bus tour around town to get oriented. I snoop out the independent music scene and local street art that attracted Marika to Melbourne, and eat dinner overlooking the Yarra River. Melbourne at night is lit up like Christmas. Everywhere I turn, it’s crawling with people. There is Chinatown. There are sushi places. There is always some hanging-around dog or statues of dogs. This is it, I tell myself: wherever Marika made home there would be dogs, lights, sushi, music, and water.

In the morning, on the way to the famous Victoria Market, I scatter some of the ashes in the pretty Yarra River as people hurry off to work. By midday, I board the train at Flinders Street Station to spread the rest at the Victoria University of Technology Saint Albans Campus, home of the Nursing Program. It’s not a long trip. Leaving the train, I follow the trickle of students from the station to the school. In this corner of Melbourne, there is little else to head to.

It’s a new campus, still under construction. Fences, a few young trees, some makeshift structures … everything calls out ‘in process.’ I look around at the barren place. The single campus fountain sits dry, filled with garbage and fallen leaves. Some friendly students assure me there are flowering shrubs in the spring. A raven caws. Nervously, I hug the bag of ashes and keep walking. I try to imagine Marika going to school here. But something feels wrong.

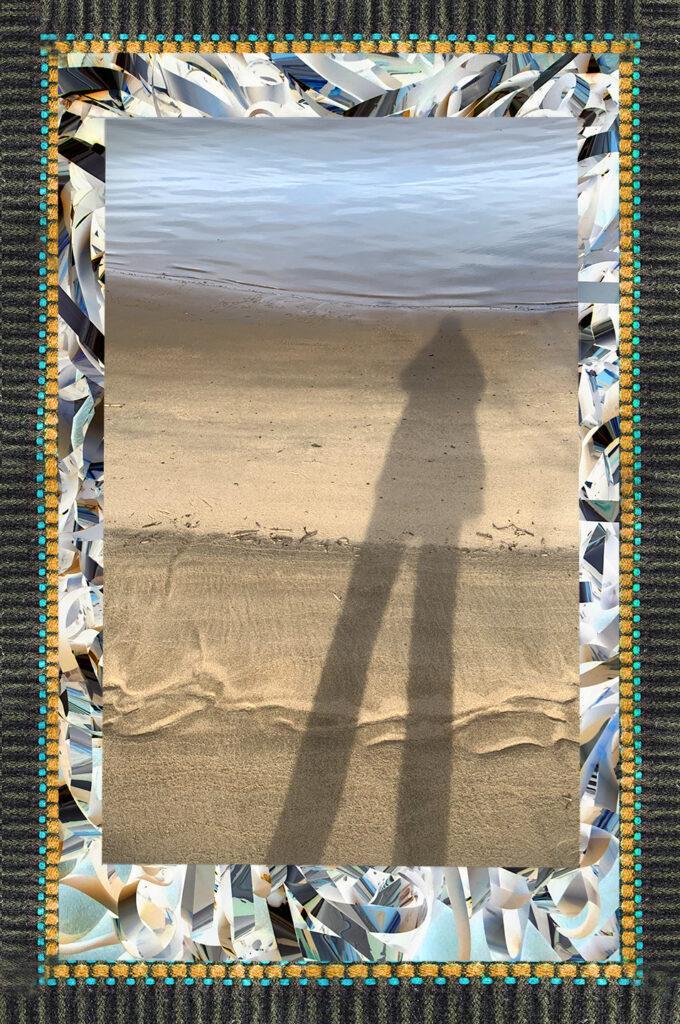

There is no water. Anywhere. I’ve come all the way out here with the last quarter of Marika’s ashes and I can’t leave her in this place. I walk the tiny campus, twice around, looking for a good spot. Marika would have been here now, in April 2012. The students passing me would have been her classmates. But I cannot see her. I can’t feel her here.

In fact, I’m pretty sure Marika would hate it here. Is this coming from Marika or is it my own hang-up? I’ve only got today to figure this out because early tomorrow morning I’ll be leaving Melbourne, heading back home. And I need to finish her ashes. Today.

Gingerly, I sprinkle a bit in a spot near the Artistic Café, where students sip soft drinks on outdoor tables with bird chatter overhead. Then suddenly, mid-scoop into the ashes, I find a little tag in my hand. Cheap gold-colored, tinny plastic. It has a number on it, and says Mount Hope Crematorium. I take this as a sign to stop. In tears, I stuff the bag of ashes back into my pack, and rush back to the train station, back to Melbourne proper, and up to University Student Services on Flinders Street where I pester the poor clerks who have no idea why this desperate woman is pleading for help to find the daughter she’s convinced is supposed to attend school here.

“Marika Warden isn’t on the roster for Victoria University,” one clerk says as she fusses on her computer. Immobilized, I finally remember to breathe. I’m muttering madly to myself, Think. What’s missing here? Marika said she was accepted. She showed me the letter on the computer. I paid a deposit with a personal check. Two checks. I wrote two checks to two different universities. What was the other school? “Oh, here she is,” the clerk points to her screen, “University of Technology Sydney. You had the wrong university,” she says, and I burst, howling, into tears.

Why hadn’t I paid attention to this important detail in Marika’s life? I remember being happy for her, and proud she was putting together a future for herself all on her own. Maybe I didn’t believe it was possible. Maybe I didn’t want it to be. And maybe, after all we’d been through while she was alive and all I learned after she died, maybe I could never really know who this amazing creature was.

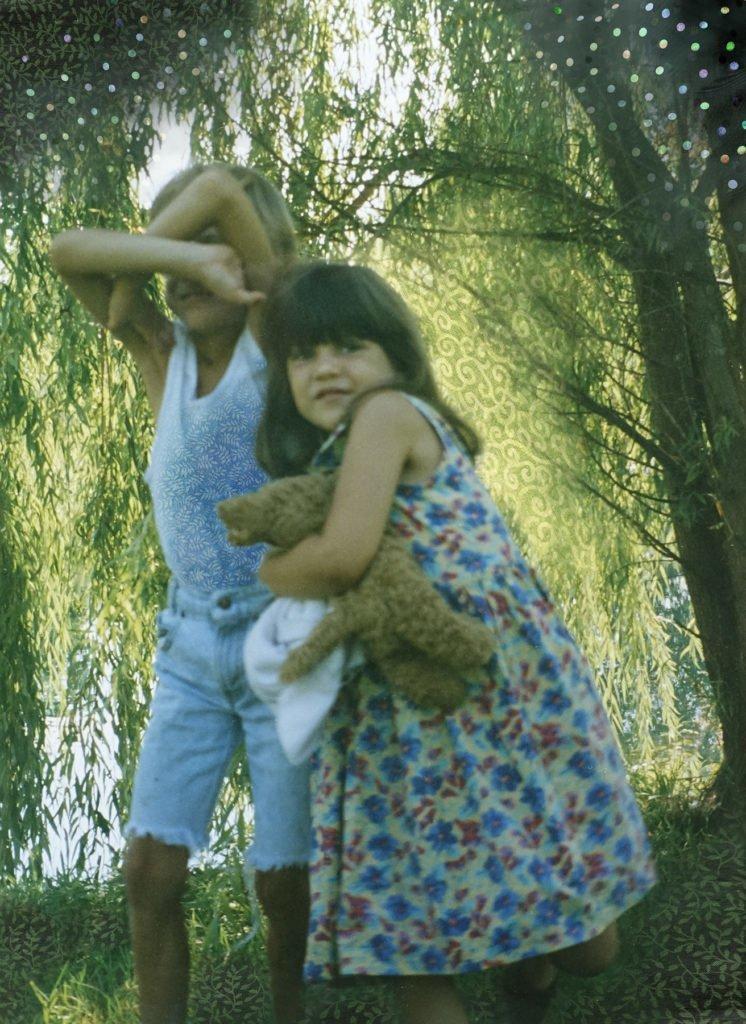

There was so much I simply didn’t know about my own daughter. Back in March 2011, shortly after the calling hours and the departure of family members who’d flown in for the funeral from Boston, Chicago, and parts of Florida, I’d crept back up to Marika’s room and spent hours tearing through her shelves. In the days that followed, I scoured her bedroom at Limbo, where Rachel had already foraged and slept, hugging the things Marika had held. But nothing contained Marika. Not for me. Until I found her words. Then I just wanted to find more of her words. Devour her words. Read them aloud. Sing them. Hang on to every last one.

Until soon, I was not only an intruder; I was possessed. I became an addict, needing, craving, begging her brother to break into her laptop, demanding of Rachel, “Where are the rest of Marika’s words?” Over the next bleak weeks, I’d copied the poems and prose. When I typed her words, I felt Marika’s heart beating. When I gathered the best of the songs and poems, and Xeroxed them into a spiral-bound book, I could hold her. Her thoughts. Her hopes.

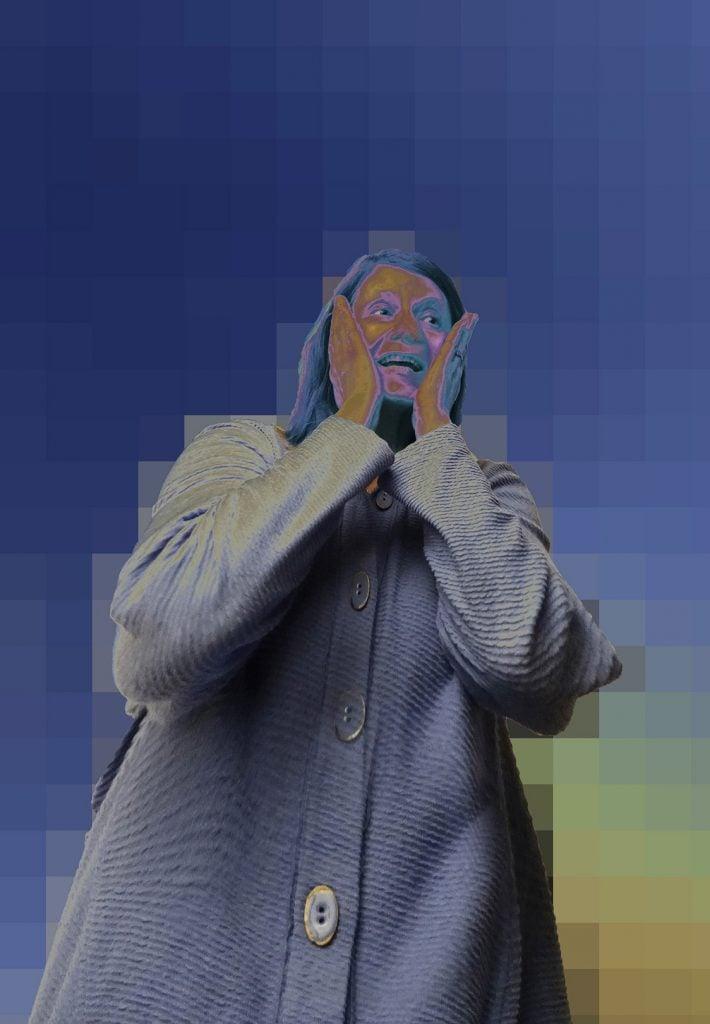

She wrote about her life; she wrote about her death. She wrote about what it was like to have cancer and how it affected her relationships. How it felt to be sedated and then wake up to everything changed. About feeling like two different people. About needing freedom. About love.

Some of her writing from before she knew she had leukemia frightened me. She’d been in some difficult relationships. She’d contemplated suicide. Torn between honoring Marika’s privacy and wanting to hang on to all her words, yet not able to stomach some of the dark ugly truths, I threw out one of the early notebooks, burying it deep in the trash. Then, in another journal, I found the page from the very night she was diagnosed. She’d picked up her pen immediately. One day she was writing about the frazzled love life that gave her pain so great she wasn’t sure she could go on living. And that night, in one turn of a page, she wrote about her leukemia. All the things I wish we had talked about, all the conversations we should have had—she wrote.

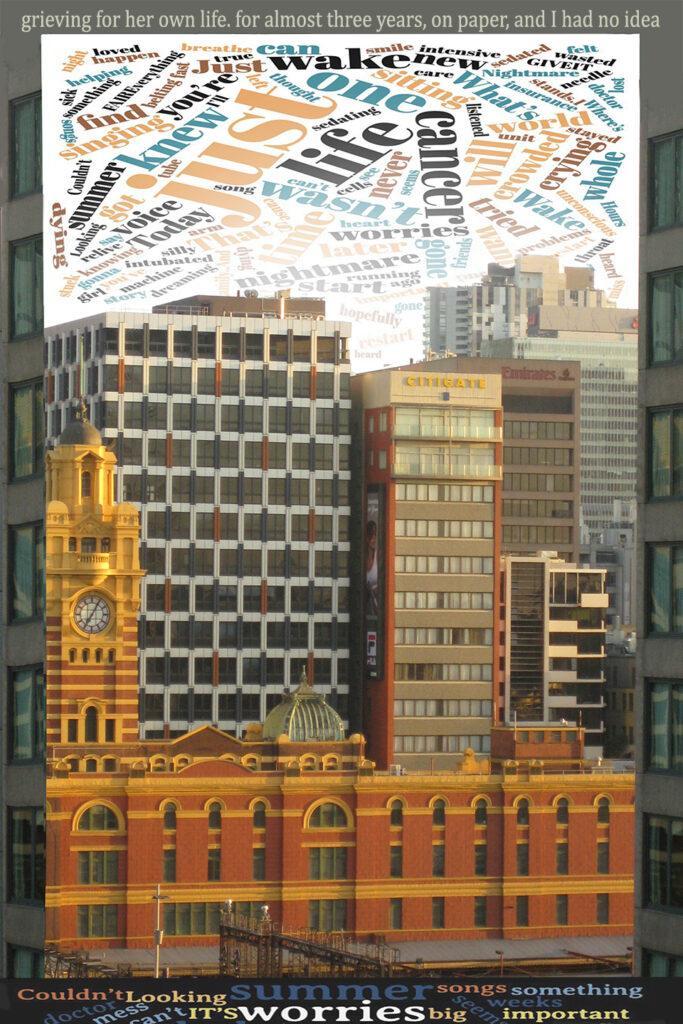

And there I was, three weeks after she died, sitting in the middle of her cluttered bedroom floor with a hot pink spiral-bound journal in my lap, first realizing that she’d been thinking, processing, and writing everything all along. Marika had been grieving for her life. For almost three years, on paper, and I’d had no idea. That’s when I first knew:

It was me. I had never been fully present to her, to the one who dazzled me most in the world. Doggedly pretending she could live forever, even as she lay dying, I was the one not facing reality. And I never left her an inch to talk about the possibility that she might die.