Depression affects the immune system. To survive bad luck, boredom, painful procedures, endless blood transfusions, and long hospital confinements when it seemed everyone else was out dancing, I conjured up all sorts of distractions for my daughter. Part of my mission was to make something magical happen each day. So I pretended the hospital was our summer resort. The lobby was an esplanade, perfect for people-watching, with the prevailing aroma of roasted coffee, and a player-less piano trilling away. The information desk was our concierge, offering restaurant menus for takeout dinners. Complimentary prune juice cocktails and ice cream cups were always available from the unit kitchen, a few doors down from our somewhat-less-than elegantly appointed room.

Depression affects the immune system. To survive bad luck, boredom, painful procedures, endless blood transfusions, and long hospital confinements when it seemed everyone else was out dancing, I conjured up all sorts of distractions for my daughter. Part of my mission was to make something magical happen each day. So I pretended the hospital was our summer resort. The lobby was an esplanade, perfect for people-watching, with the prevailing aroma of roasted coffee, and a player-less piano trilling away. The information desk was our concierge, offering restaurant menus for takeout dinners. Complimentary prune juice cocktails and ice cream cups were always available from the unit kitchen, a few doors down from our somewhat-less-than elegantly appointed room.

“If you could makeover this room, what color would you paint it?” I asked, wanting to draw Marika into my fantasy. She rolled her eyes at another of my stupid questions.

“Orange,” she grunted.

“What about the floor? Orange too?”

“Carpet.” Then she added, “And I’d make this a double bed with a real mattress.”

“I’d put a fridge in over there,” I said, grateful to get her engaged.

“Yeah, and a bar. I could use a martini.” Speechless, I looked at my just-turned eighteen-year-old daughter and wondered how many martinis she’d had.

When allowed off the unit, we escaped to the meditation room with its cool blue-green lights and crocheted blankets that hugged two stuffed chairs. I wheeled her to an indoor courtyard near the far-off dentistry wing. We roamed the endless hallways, searching for the chapel in the depths of the massive Strong. We tiptoed to the newborn babies’ window and peeked through the slats of drawn blinds to watch the tiny wrapped bundles wriggling or peacefully still.

“You were the most beautiful baby, Mareek.”

“I know,” she said, engrossed in the newborns.

“Where are they?” She growled impatiently. We were stranded in the radiation department, waiting for the transport team to take us back to the room.

“Okay, it’s been over ten minutes. I’m kidnapping you. Hold onto your hat,” I said, whirling her wheelchair around.

“Mom! Whoa, what are you doing?” she sputtered as we zigzagged wildly down the hall. “Do you know where you’re going?”

“No, but I bet I can get us back by lunchtime,” I said, surprising myself by my desperation to stave off negativity and the ensuing insults to Marika’s meager immune system. On the way to the room, we meandered through the fourth floor pediatric hall where the walls were painted in bold colors and plastered with distorting mirrors and protruding animal sculptures that begged to be interacted with. Then we were at the door to the Ronald MacDonald rooftop playground. It was deserted so we sat outside in the middle of the chain-link fenced-in yard, four floors up. From my backpack, I removed two tiny containers I’d carried around for days for just this opportunity. We blew filmy, fragile bubbles that flew off into the wind.

“Should I fetch cooked sushi for dinner tonight?” I asked in between bubbles.

“I want steak,” she said, adding “for lunch.”

“Well, if I get lunch take-outs we’ll have to eat hospital food for dinner,” I reminded her. That was our deal: eat hospital food for breakfast and lunch, eat well for dinner. “But,” I offered, “I might be talked into sharing a frozen latte from the lobby after a hospital lunch.” She scrunched up her face and declared,

“Double iced mocha with chocolate ice cream. I want my own.”

“Deal. Do you think we’re locked out?” I asked, nodding toward the door that had closed behind us when we went outside, a last-ditch effort to throw in some further intrigue.

Friends were the best diversion. They occasionally made the two-hour trip from Ithaca to Rochester. Cassie, Carla, Shoshana, Golda, Jeff, Julie, Lamarr, Rachel, and more. Cassie brought an enormous stuffed dog. Carla brought Silviana. Julie always climbed into bed with Marika. There was lots of pizza and Chinese food. And laughter. I left the room most of the time when her friends came. But not before I scanned them for signs of pinkeye or colds.

As it got closer to college orientation, the visits died down. Except for Rachel.

“How’s she doin’?” Rachel asked from Ithaca, ninety miles away.

“Well, it’s funny you should pick this moment to call. She’s in radiation right now. She had a high fever last night and we’re waiting to see…”

“Well tell her to cool down,” she said, “and tell her I miss her.” They called each other “Wifey.” Rachel, a year older, had recently passed her Emergency Medical Technician training. When not in college, she worked for a local ambulance company. I felt totally comfortable sharing the details of Marika’s condition with her. Especially since she always found us, whenever Marika’s health crashed, wherever we landed.

Several times a day, I rubbed Marika’s feet. She didn’t like asking.

“Mom.” She would shamelessly wave a foot in my face and frown pathetically. Foot rub.

“How do you do that with your mouth?” I asked, trying to mimic her pout. “It has to be a short one. I have to write a paper for my class.”

“Why don’t you pull the cancer card?” she yawned.

“What cancer card? What’s a cancer card?” I asked. She smiled with closed eyes, and wiggled her toes in anticipation of the foot-rub.

“Just tell your teacher your daughter has cancer, Mom. Then you won’t have to work so hard.”

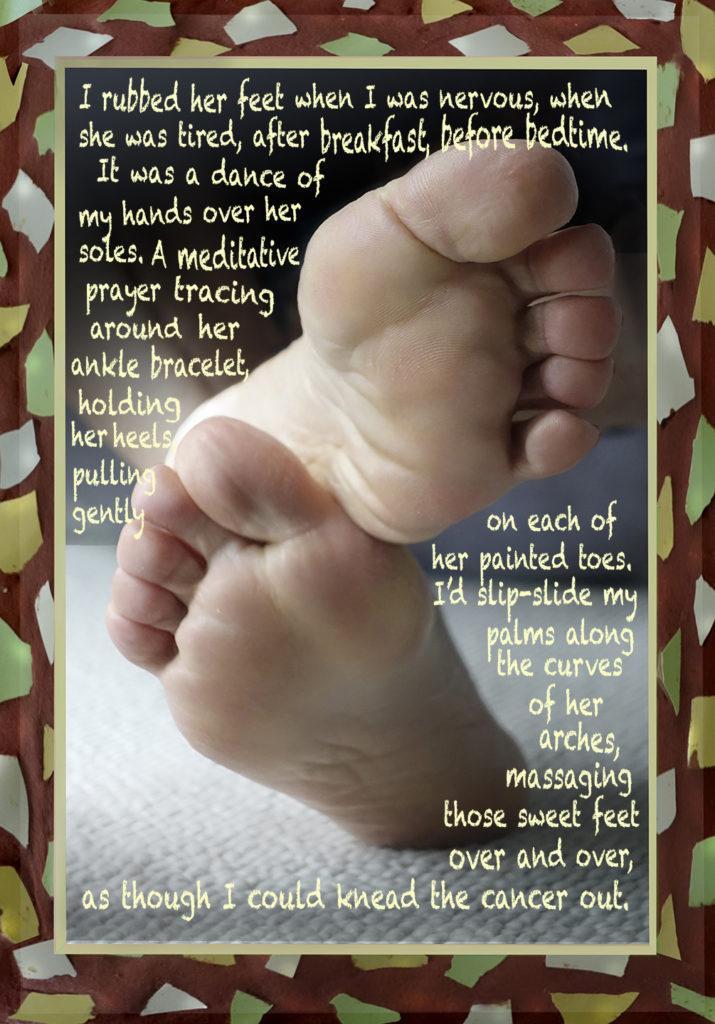

Marika never had to do much to get me to rub her feet; it was the only time now, other than grasping hands when she got shots, I could touch her. So I rubbed her feet when I was nervous, when she was tired, after breakfast, before bedtime. It was a dance of my hands over her soles, a meditative prayer tracing around her ankle bracelet, holding her heels, pulling gently on each of her painted toes. My thumbs lightly pressed butterfly-indentations over the balls of her feet. And finally, I’d slip-slide my palms along the curves of her arches, massaging those sweet feet over and over as though I could knead the cancer out. On hearing bad news, I’d grab her feet. It was my way of hugging her.