Eleanor from the Loch Ard Motor Inn gives me a ride to my first site of the day. She and Margaret take turns running the small motel. Not wanting to spread sadness, I haven’t told them my story. But I must seem lonely to them. They do everything they can to make me feel welcome. Driving me around Two Mile Bay, Eleanor points out landmarks for my return trip on foot. And suddenly, right in front of us, by the open back of his car, stands a completely naked man. A surfer. Very handsome. He chuckles calmly and waves at us. Eleanor and I giggle like giddy schoolgirls. Our faces turn shades of red. And I wonder how he can so gracefully accept this embarrassing collision of his path with ours. If it had been me caught in the nuddy, I’d be replaying the scene for months in my head, mortified.

Soon after, Eleanor drops me off by a trail through low scrubland. The atmosphere is murky and misting. I nervously note there are no tourists around. Determined to see more sculpted limestone features of this Southern Ocean Coast, I venture forward alone through thick fog, down stairs and long sand paths to find The Arch, the partially collapsed London Bridge, and the stunning sinkhole called The Grotto. I feel compelled to visit, like they are my ancient aunts who have known every joy and sadness in the world. These are not just hollowed-out rocks. These are places that make me want to sing, that make me cry. It’s a feeling of coming home. Some people have the Bible or Quran or some doctrine to follow. Some look to their ancestors for direction. I look to the sky, to the ground, to mountains and great masses of stone, to the paths people have trodden for ages. Where I feel very small and insignificant but very much a part of belonging. Where for a while I can stop searching because I am filled up with something. Something that resembles grace and gratitude. And awe. I feel blessed.

West of Port Campbell and Two Mile Bay, in the Grotto, I watch water seep into the cavities of the rocks at the ocean’s edge, and look past the cave walls and still pools to the sea beyond. Marika had not come this far on her trip. So many wonderful things she did not get to see or do. All the beautiful things she knew were out there somewhere. I’m going to find them. For her, I promise.

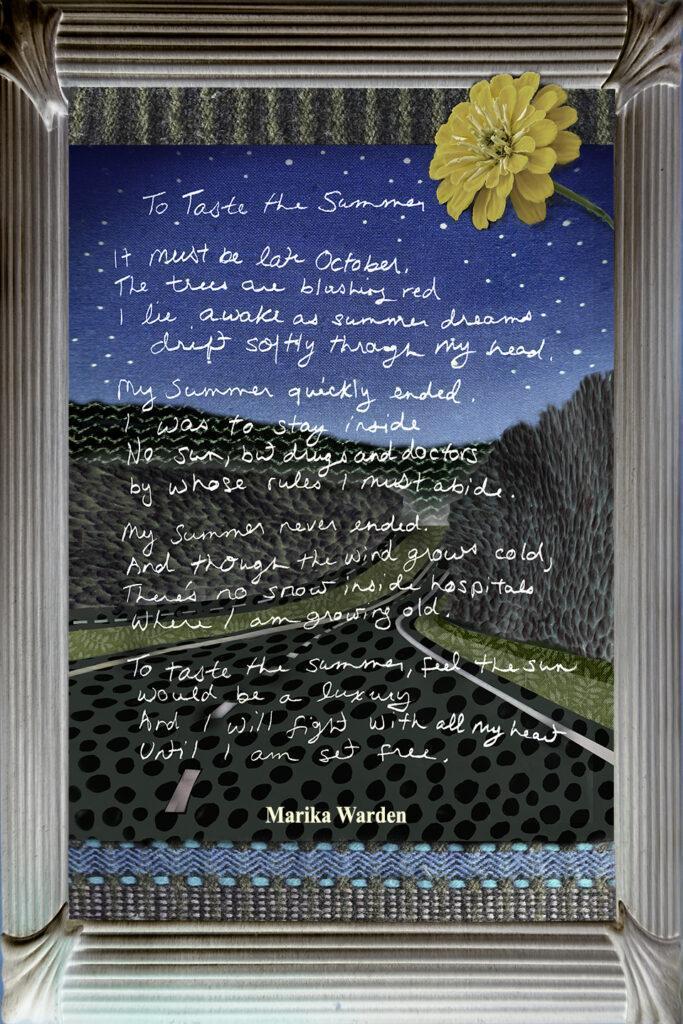

The sun comes out again. I imagine Marika riding piggyback on my shoulders once more as I climb back up the huge staircases to the Great Ocean Road. After a while on the long walk back to Port Campbell, I pass a yellow diamond-shaped sign with a kangaroo graphic. It is a warning to drivers to watch out for animals in the road. Just beyond, a huge heap of kanga-road-kill lies in my path. I stare dumbly at the carcass for a moment. And inch closer. It has long black nails on black hands that reach for the sky. It looks like it’s praying. In my mind, I make it rise up and shake itself out: My kangaroo-ghost stands much taller than I. I suddenly feel lighter as Marika steps down off my back and climbs onto the kangaroo, piggyback style. “Mom, really?” she asks, her eyes brightening like I’ve given her a new MINI Cooper convertible. “Yeah,” I reply, “Just keep her away from the roads.” In my mind I watch them ride off together, inland, to endless rolling hills of grasslands with windmills, farms, and scattered patches of dark trees. Far away from this Great Ocean Road where I have one day left to wonder what I’ll do once Marika’s ashes are gone.

There are too many questions. Like, how do I make Marika’s life count for something? And what should I do with my own life? How do I gather my own ragged remains, drag them back home, and breathe new life into my once intact world?

Back in the office at the Motor Inn, Margaret laughs her hearty laugh. She’s just agreed to keep a stray dog at her house where she already has six dogs, two cats, a wallaby, and too many birds to count. A motel guest who is in the middle of his family vacation really wants the stray dog. It had followed him on and off the beach all day, and he promises he’ll come back for it. If Marika were here we’d be smack in the middle of this drama around the dog. She’d beg to keep it herself, and I’d dance up and down in a fit, trying to make her see sense. It’s someone else’s scene now. I smile, listening to the eruptions of Margaret’s chortling. How does one laugh in the thick of such craziness? But laughing is so much more gracious a response to a stressful situation than seething in rage or howling. I vow to put more laughter into my own life. Because this whole thing of living, of loving, is really very laughable. Who learns to go through it right? Just when you think life is good, you get booted from behind and someone you love dies, and everything changes. Then you scream and wail with the pain. Not fair, I can’t go on, Why me? To laugh is to recognize that all of it is incredible, even so.