Eighteen years old. I remember when I turned eighteen. Laurie, a year younger but in the same grade, was already driving. I was not. I never liked movement, didn’t trust I could survive skating, bicycling, diving, Kiddie City Amusement Park rides … I did not dare challenge gravity. Being alone, getting lost, drowning, … going downhill in any manner or losing control terrified me. There was no major trauma in my memory, but I lived in dread of the bad things that could happen. I might fall. The ground beneath me could breach. There could be blood and it would hurt. I could die. I was afraid of it all. Nonetheless, at eighteen I had a life. Laurie and I had friends, parties, places to go. We had jobs and were getting ready to go off to college. Home was smothering. So close to freedom and independence, we counted the days ‘til we could come and go as we pleased, ‘til we graduated and got away. At eighteen, with all my trepidations, the worst thing I could imagine was being stuck with my mother. In a hospital. For months.

Eighteen years old. I remember when I turned eighteen. Laurie, a year younger but in the same grade, was already driving. I was not. I never liked movement, didn’t trust I could survive skating, bicycling, diving, Kiddie City Amusement Park rides … I did not dare challenge gravity. Being alone, getting lost, drowning, … going downhill in any manner or losing control terrified me. There was no major trauma in my memory, but I lived in dread of the bad things that could happen. I might fall. The ground beneath me could breach. There could be blood and it would hurt. I could die. I was afraid of it all. Nonetheless, at eighteen I had a life. Laurie and I had friends, parties, places to go. We had jobs and were getting ready to go off to college. Home was smothering. So close to freedom and independence, we counted the days ‘til we could come and go as we pleased, ‘til we graduated and got away. At eighteen, with all my trepidations, the worst thing I could imagine was being stuck with my mother. In a hospital. For months.

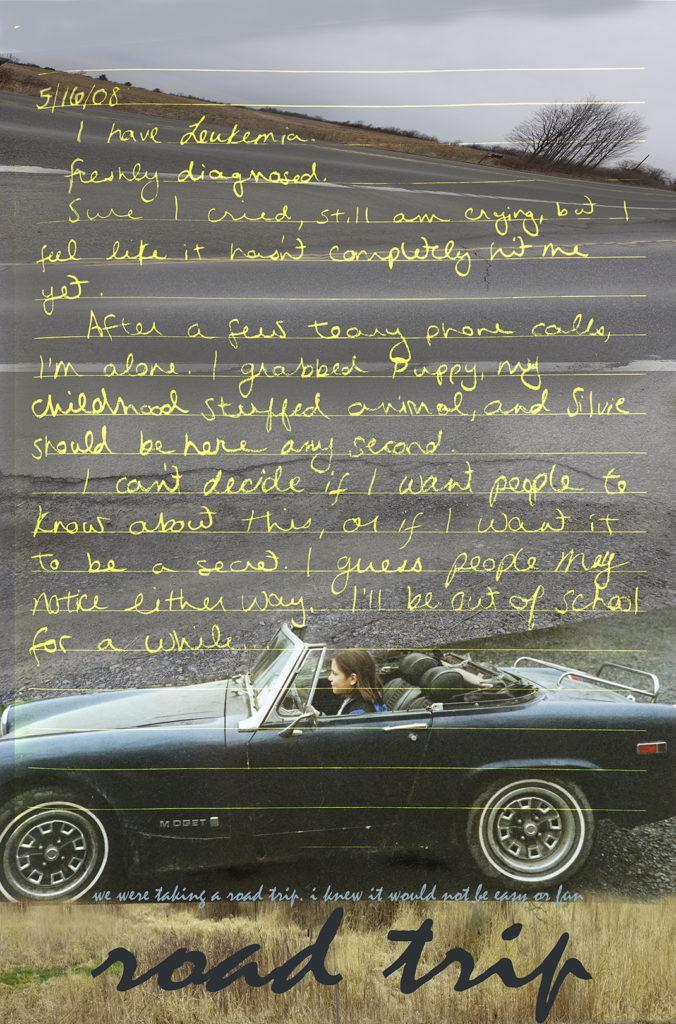

“Mom, I’m going on a road trip,” Marika had announced the summer before the diagnosis, shortly after she passed her driving test.

“I don’t think so,” I’d said.

“But Carla and Silvie are going.”

I called Silviana’s mom to confirm.

“Paula, did you say yes to the road trip?” She had. And I saw nothing but white-flashing warning lights. Until I heard her plan. In our mother-daughter crowd, if there were valuable lessons for our children to learn, we would creatively bypass saying no. We came up with a compromise. Silviana, Carla, and Marika took their road trip to Rehoboth Beach in Delaware, six hours away. And Paula and I followed them, in Paula’s van, three to four cars behind. We all stayed in the same hotel. We pretended we were not related. Paula and I were given the room next to our girls, unbeknownst to them. They whooped and warbled all night long. Eighteen. Free from moms. Except at dinnertime when we’d meet up in restaurants. Dinner is always the time to convene in peace, over good food. No matter where you are or whatever else is going on.

Three weeks before the diagnosis, Marika had totally disowned me. And my rules. She had a forbidden party while I was on an overnight hiking trip. Coming home to the fumes of Lysol, I roared about the horrific state of my house. I didn’t acknowledge what must have been a gargantuan effort to clean up. More worried about the house than her safety, the ordeal of her trying to contain an out-of-control situation did not occur to me.

“Mom. So what. So my friends smashed the Adirondack chairs. So they threw the stove burners into the pond. They left a few cigarette burns on the deck. Get over it!” She had told me more than once to go fall off a mountain, go drown, take a long hike and get lost. “Get a life, Mom.” Cracks of white lightning stabbed me when she spoke like that. It used to make my hair stand on end for hours, but over the last few years my neuro-receptors had worn down. By the spring of 2008, I rarely even winced at her caustic comments.

Marika didn’t always act like a brat. Like two weeks after the forbidden party, on Mothers’ Day, I arrived home from a hike to a trail of Hersheys chocolate kisses leading from the front door to all over the house.

“Mom, you hafta follow the chocolates and read the clues to find your present,” she’d said, grinning proudly. And fifty chocolate kisses later I found Caesar salad, seafood linguini, flowers, and candles on the table. And a chocolate cake. “Sorry, it’s a Wegmans cake. I didn’t bake it, didn’t wanna make a mess.”

The first morning at Cayuga Medical Center, the staff asked Marika for permission to include her parents in the discussion of her health. Surprised at this new authority, she shot me a delighted glance. Caught totally off guard myself, I dropped my jaw and glared at the doctor, shocked that in New York, at eighteen a kid is “the adult in charge.” My daughter had the right to exclude me from being involved in her medical treatment. Marika held her stuffed Puppy in the crook of her IV-laced arm as she agreed to include her parents and Laurie. It was her first medical decision as an adult. She got that one right. So there I was, and we were about to start a journey. Except for short weekend breaks when her father and his wife relieved me, I would be right there.

And I would not want to be anywhere else. Nothing could keep me away. Not her cursing and calling me names, not blood or vomit. Not the prospect of late nights on emergency car rides to some who-knows-where hospital with frantic interruptions to find a restroom. Or her angry evil eye if I said the wrong thing. In my mind I was thinking, road trip. We were taking a long road trip. Together. I knew it would not be easy or fun now that she had good reason to be cranky. But it would not last forever. And it was my last chance to be there for her. With her. Before she grew up and moved out of the house completely. This was where I wanted to be, where I had to be.