There’s something I should have mentioned long ago: I have no religion. I mean, I don’t know if I believe in God, or in scriptures, or heaven, or in any of the various teams directing members about how to worship or who to trust. Religion, like politics, is one more thing that divides people. I don’t subscribe to any sides even though it means I’m often treading on shaky ground.

I like to imagine there’s some invisible thing out there, some entity that’s always creating, giving and taking. Watching over us all. I feel closest to this thing when I’m by an ocean or hiking in the mountains. Regularly, looking up at the stars or out across valleys into the hills, I send out grateful thanks to it. When I feel lost, this something reminds me I’m not alone. It counsels me to treat others the way I’d want to be treated, and it assures me I will never understand the ways the world works. Occasionally I beg for help or protection. And then it fades as it bids me to do my best and be strong.

In times of crisis or loss, I’ve always envied those who have faith in someone or something beyond this world. Life would be so much easier if I was chummy with God or had some indisputable doctrine to live by.

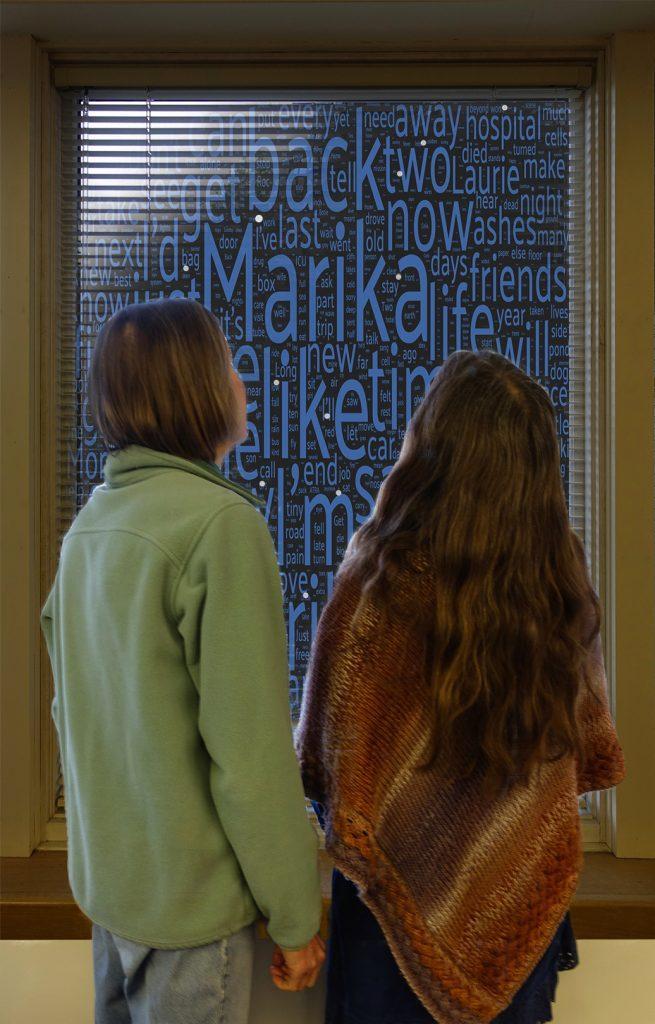

Back on the last day of June 2009, Marika’s burgundy snowflakes were all over her again. Her job as lifeguard and boating counselor at Stewart Park Day Camp was to begin the next day. It was supposed to be the summer to make up for the loss of the previous summer.

“I’m fine,” she said, dully, when I caught up with her at Strong Memorial. She’d already been put on intravenous arsenic, the standard second line treatment for her type of leukemia. “I’m bored,” she said, meaning she felt trapped and knew her summer plans were now shot. I rubbed her feet and made mental notes of what I would fetch from Wegmans.

“Have you heard anything from Jake lately?” I asked, suddenly needing to know more about the other almost-adult child with leukemia. Whenever we had a setback I’d check the status of the other players, as if we were in some sort of race to beat cancer.

“He hasn’t returned my messages,” she said, and turned away. We settled into our old established patterns for hospital confinement. But “fine” and “bored” didn’t last long.

“She didn’t eat the Cheesecake Factory takeout,” I whined to Laurie.

“Robin, she’s depressed and in pain. You don’t eat when everything between your hair and your toenails hurts.”

“And now they stopped her chemo. What does that mean? Are they giving up?”

“That’s just temporary, until they make sure she doesn’t have an infection or pneumonia again,” she assured me. But two days later, Marika was short of breath, and the Roc Docs put her in the ICU to avoid respiratory failure, her signature crash landing. Then she did crash and was put on the ventilator once more. And as she lay there unconscious, the cascade of complications compounded. Low blood pressure. Liver malfunction. Kidney failure. Her heart developed an electrical abnormality leaving her vulnerable to lethal arrhythmias. Inefficient heart patterns. My own heart smashed into my stomach. I flailed about wildly to grasp something stable, anything that might hold me or help me find solid ground. I rubbed Marika’s feet fiercely.

A portable dialysis machine was wheeled in. It looked like a cross between an ancient refrigerator and a big old-fashioned tape recorder standing on its side. I stared at it skeptically. It hummed and churned. A wheel spun around as Marika’s blood went in and came back out. I watched the colors of the input and output to discern any differences, and asked questions of the technicians who monitored the process constantly. There was no one else to talk to. I was miserable. During dialysis, for some reason I was not permitted to rub Marika’s feet. Desperate for connection, by the end of the second week in the ICU, I left my Sleeping Beauty for a weekend at home when her father came to take over. Then, in Ithaca, I couldn’t face anyone. People said, “How’s your daughter doing? I’m praying for her,” and I didn’t know how to answer. If they were kind or tried to hug me, I broke down crying.

A cousin called to tell me a group of nuns in New Jersey were praying for Marika. Another cousin brought Marika’s name up in a service at his temple in Tucson. “We’ll keep her in our prayers,” various friends promised. I thanked them, “We need all the help we can get.” Visions flooded my head: Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music, cloistered away in an abbey of somber nuns, singing and praying in heavenly harmony. Prayers, churches, synagogues, mosques, and monasteries were all foreign to me. But if more people were uttering Marika’s name, and wishing us well, it couldn’t hurt.

Still, for me, then, the only sure solid thing in this world was my daughter. I rubbed her feet and wondered, would those nuns really pray for a girl whose mother practiced no religion?