Cradling the bag of Marika’s ashes on Bells Beach, in the southeastern coast of Australia, I dip a hand into the cool graininess and it comes out chalky. The wind throws my first fistful of Marika back at me. It takes a few tosses to get the hang of it. Soon the ashes dance from my hand and curl away with the wind before they dust the water. It’s mesmerizing. It’s like playing. Like when I used to swing Marika around in the pond singing “Ring Around the Rosie” and “What Shall we do With a Drunken Sailor.” I would raise her up and dump her into the water. Ashes, ashes, we all fall down. “Again,” she’d beg, “again.” Now, sprinkling small handfuls, I watch smears of ash clouds gently rock on the water’s surface. Sand drags through my grasping toes as I slog through water that alternately swells and retreats. At each toss, the sweet grains of Marika drift slowly beneath the surface as the ash clouds rock and recede, and rock and recede, and rock and – BAM! Crash. I gasp. Cold. Wave. Almost knocked down. It fizzles away. Fast. But I’m soaked. Catching my breath, I look around. No one is near. If I drown or am swept away, I might never be found.

Half the precious ashes are gone. I hug the shrinking bag close to my pounding heart. Rogue wave. Enough ashes for today. I’m shivering. Still stunned. And wondering how I’m going to do this. How can I throw the last bits of my daughter to the sea and then return home to the other side of the world without her? And what will I do about Puppy? I pull the stuffed animal from the pack and pose it on a rock. Giving Puppy “back” to Marika is part of the mission. I’d planned to cremate Puppy on a beach, but fires are prohibited all over Australia except in protected barbecue pits. I’m squeamish around matches and lighters anyway. Marika was right. I’m a wimp. Scattering ashes is hard enough. But, barbecuing Puppy?

Shortly after Marika’s birth I had bought Puppy. Drawn to her myself, I gave her to the daughter I loved more than myself. Puppy went everywhere with Marika, and may even have gone to Australia and back. Puppy was always my key to communicating with Marika, often my only chance of swaying her to see reason. My words came out differently when channeled through Puppy. Puppy didn’t say, “Don’t you have homework to do?” She said, “Can I do homewawk wiv you?” How can I destroy Puppy? Ragged love-worn Puppy. With her long floppy ears, she often got mistaken for a rabbit. She looks a little haggard now in the sun with her saggy stuffing. Propping her upright on the rock, I remember regularly fishing her out of the hospital bed and posing her so Marika, returning from radiation, would find her on top of the bed, hunched over a tea mug with a napkin and cookie, like Puppy had a secret life of her own. I snap Puppy’s photo. Okay, what a dope, what the heck, it’s just a piece of stuffed polyester. But no, Puppy is not only my connection to Marika. She’s a part of myself I can’t let go of yet.

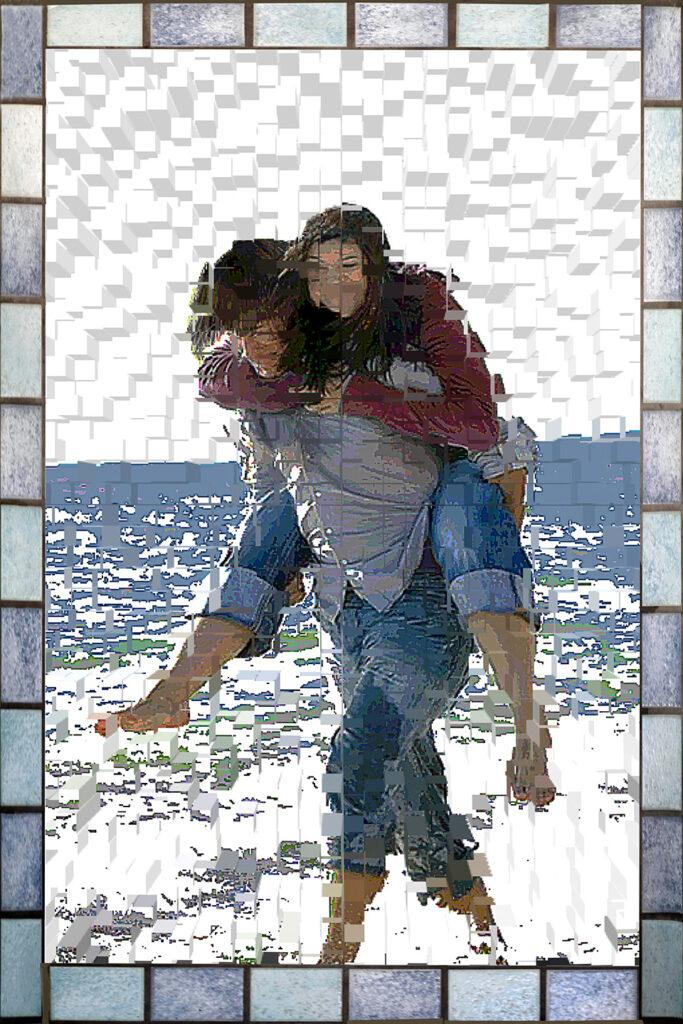

The trip back across the beach and up the long sets of stairs is lonely. But by the time I reach the heathlands, I feel Marika riding piggyback on my back again. She has fallen asleep now. Her head rests on my shoulder, and I hear tinny music sounds from her iPod ear-buds. Plodding on under the weight of her, I think about my own time for being carried. What did my own mother carry me through? That day in the waves at Jones Beach, when I lost hold of her hand, did she panic? Did she know, for a brief time, how it feels to lose a daughter? Was she plagued with thoughts of what if, what if, what if, like an ongoing heartbeat? It must have been hard this past year for my mom to see me so empty, carrying around only memories of my only daughter. She can’t stand to see me grieving. Maybe that’s why she tells me to get over it.

It boggles my mind to consider all the caring and carrying that every person who ever lived represents. Each one of us was carried, fed, and tended to. In one fashion or another, someone keeps a child from ruin. Then comes growth and change as the young life evolves into its own person. And finally comes separation. Into two strong, independent but deeply related beings. At some point the child begins to carry herself off. And the mother who held tight begins to release. There is a healthy split as mother and child divide into two. This is something one should be able to count on: like the tides, like summer following spring. Like your children outlasting you. You go through the normal processes of life and then—separation. But that was interrupted. Marika died. Separation, when a mother’s tug to hold close is not opposed by the daughter’s push to be free, is like fog. You vaguely sense something moving but cannot grasp exactly what or where it is. I envision all the love I invested in Marika wafted up into some universal cloud, a collective care blanket encircling the earth.

When the first anniversary of Marika’s death approached, my family and friends expected me to be done grieving. It was time to let her go, they said. But I wasn’t ready. I wanted to keep her. I could hold forever the memory of unending power struggles with my beautiful, cranky, uncompromising daughter. Besides, she had already written how to live on: she was going to carry her friend Jake who died. So I would find ways to carry her. With me. For the rest of my time. Until I myself must finally be carried out.

I carry Marika out again the next day. Her ashes. And since it’s a Thursday, there are no public buses coming or going in the little town of Torquay. If you have no car, you can only come to or leave this place on a Monday, Wednesday, or Friday on the public V-Line buses. Eager to start the next part of my journey, I book a spot on a private tour bus coming in from Melbourne in order to get to the other end of the Great Ocean Road. Which is how Marika traveled, hopping on and off a tour bus at a bazillion different stops.

The tour bus takes me to the Great Otway National Forest where giant ferns grow in thick moss, and ancient trees with trunks large enough to live in, climb to the sky. There are endlessly cascading waterfalls. This place is magical. It is dizzying. I smell the earthy magnificence of eons of time. If we were time travelers, Marika and I would be colliding into the same brief moment. She was here only two years ago, standing in the buttresses at the base of a primeval tree, posing for a photo. Which tree? From the elevated boardwalks that wind through the dense rainforest, I look around at the huge stands of mountain ash and myrtle beeches estimated to be two thousand years old. Gazing up and down, I see how infinitesimally minimal our being here is. My love, my grief, all the things that consume me are like one single tiny spore on a fern in a massive gully of ferns that have been reaching out for thousands of years from under immense forests of towering trees. Time is the endless sky beyond the forests. I cannot fathom it.

“The bus,” a fellow passenger points to his watch. Last to board, I fall into my seat as the bus takes off. It stops at a convenience store in the middle of nowhere, for lunch. It stops at a site where wild koalas hug eucalyptus trees, and bright-colored parrots land on my head. We visit lookouts, and learn the legends of the Shipwreck Coast. And towards the end of the day, the bus pulls into the petite town of Port Campbell. It drops me off at the Loch Ard Motor Inn, home base for the third leg of my journey.

Two women laugh heartily in the back room. I wait at the desk, listening a minute before I call to them. One comes out smiling warmly at me. That’s all I need to feel at home. And in my new room, I assemble the little altar on the counter under the hanging TV, and pose Puppy hugging the bag of ashes. The chocolate is gone but I lay out colorful ticket stubs from the bus tour, and the photos. Holding the old photo of Marika on Bells Beach, I touch the bag of ashes.

“Thank you, Mareek. All those gifts I gave you, all the best things, you’ve given back to me now: Suki, the cowboy boots, your love of writing, Puppy, Australia, … so much.”

I’d given her life. And maybe, in some way, she was giving life back to me too.

“Mom, get a life.” Maybe that’s what I’m really doing here in Australia.