There is always some anxiety as I wait for guests to arrive. My friends are so different from one another. They range from Marika’s age to my mother’s age. For the Feed and Reads I’ve gathered them from my hiking group, from foodie endeavors, former workplaces, and past mother-daughter relationships. One friend’s daughter will join us, and also a woman I’ve never met who felt linked by loss. And Rachel. If I can reach her.

“Hey Rachel, where are you? You haven’t called or emailed me in over a month. I’m getting worried,” I leave multiple messages on her cell, “You’re coming to the Feed and Read aren’t you?” Rachel usually communicates with confidence, like she’s the Mayor of Cool. But when I last spoke to her she’d sounded almost suicidal. Too wrapped up in my own pain, I’d never really considered how Marika’s death affected her best friend.

Soon I’m more warmed than worried, looking around the first assembly of my readers. They introduce themselves and talk like they are old friends. And in the months to come, they will be. In their courageous effort to help me, they will discover familiar connections and create new ones. But there are two who are missing. One is Andrea. She had often “borrowed” my children over the years, spoiling them and stretching their minds. She’d visited Marika several times in the hospital. Andrea had given me my first teaching job, knowing what I could do long before I did. Two months ago we walked in the woods as yellow leaves fell. What kind of horrible joke was it that she was recently diagnosed with cancer herself? I wanted to be there for her. But wearing her head wrap and hoop earrings, she so resembled Marika, I could hardly look at her. Now Andrea is too sick from chemo to join the Feed and Reads.

The doorbell rings and I run to answer it. Rachel.

“Sorry I’m late,” she says, all bubbly at the door.

“Look at you!” I gush. “Your hair. You look adorable. You look – happy.” She looks like she owns the world and has just walked into her own birthday party. Her makeup and manicure are gone. And her hair is shaved off except for a bit at the top.

“It’s a Faux-Hawk,” she says, brushing at her almost bare head. “Do you like it?” It’s freezing outside, but she’s wearing a wife-beater undershirt, neon Michael Jordan sneakers, and low rise baggy khaki shorts that might be her dad’s. She looks like the beloved janitor from some old TV show. But she still has on the fragile silver necklace that was Marika’s.

“I’ve been sober for fifty-six days,” Rachel announces at the table as we feast on butternut squash soup, cheeses, salad, sushi, and shrimp cocktail. She proudly shows off her tattoos. One particularly huge one spreads across her ribs on her right side, “Be strong when you feel weak,” a quote of Marika’s. I’m very aware of how different Rachel is, from before, from the others. And I’m proud of her, like she’s mine.

When the meal is over, we move into the small living room for the reading. A photo of Marika sits on a tiny table next to me. Next to it is a box of tissues. And pencils and notebooks, for comments.

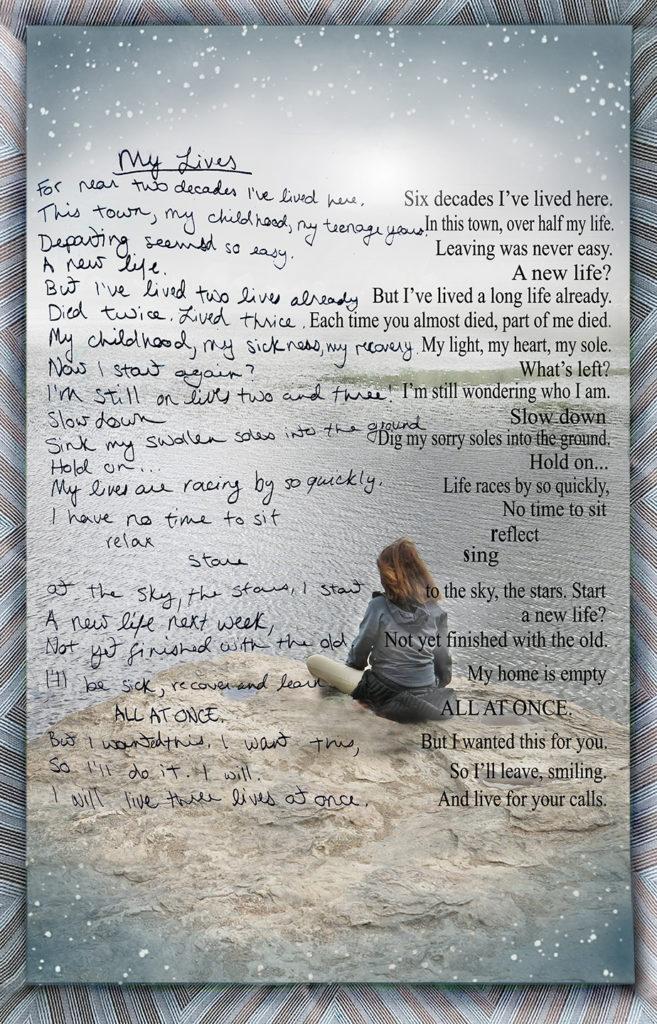

The Feed and Reads will go on for over a year. Whenever I have a couple of new chapters to share we will feast. My work is the focus at these gatherings, but everyone here knows grief. Before and after I read, we share our stories.

“It was just like that for me when my husband was in the hospital, before he died,” says Jane, the friend-of-a-friend I hadn’t known before. Next to her, Barb, who will host most of the Feed and Reads, sits stunned, holding a tissue in mid-air between her lap and her face.

“After my husband died I wrote him letters too,” says Annette, whom I’ve known over twenty-five years, “It was a powerful healing tool.” Celia, who remembers everything, brings the group back to my story saying, “You forgot to mention the prom. You have to write about the prom.”

It’s as if they all know I need them here. They somehow sense the best way to support a grieving parent is to show up and listen. So I keep writing and rewriting. To read aloud my daughter’s story. All a bereaved mother really wants is for her child to be remembered. For the rest of my life I will listen patiently while friends ramble on about their kids graduating, getting their first real jobs, getting married … and there will be no more news of Marika that I can contribute to the chatter. But here is my time to tell about my beautiful brave girl, her accomplishments, and her extraordinary passage through the bloom of her short life.