They are out there, all around us, even here in small-town Ithaca. Around every corner, at the mall, strolling on the Commons, in Wegmans picking through the tomatoes. There are more and more scarred young women with denuded brows, wearing head-wraps to hide tender skulls, pristine and bare like babies’ bottoms. Is it just me noticing the increase of these brave veterans of private wars? I can picture entire armies of these women, these chemo-hardened warriors. At one time I would turn away, unable to look at anyone who looked like a cancer patient. But now, as when my son Greg joined the Army and I’d practically hug anyone I encountered wearing digital camouflage, I find myself drawn to these cancer-surviving women. They are my cousins, my family. We are blood relatives: I’m giving blood; they’re getting blood. They are my tribe, along with their mothers.

Blood donor, mother of two, Marika’s Mom, Army Mom, lifeguard, caregiver, lifelong student, artist, small business owner, teacher … in February 2012, I consider my various past roles, wondering who I am now and what’s next. Since my daughter died, women reach out to me; some I know and some strangers. They tell me they lost a son, or their daughter died too. They hug me. Welcome to the club, this is forever, they say. Bereaved Mothers. Our stories have similar endings. Our bonds are quickly cemented solid. Unlike the land-mined deserts materializing between me and all my friends who still have daughters. They are taking them to Cancun or Paris, while I am putting together a solo trip to Australia to scatter Marika’s ashes. My life is out of whack. I’m not prepared for any of this. How can I begin a new journey? Begin anything?

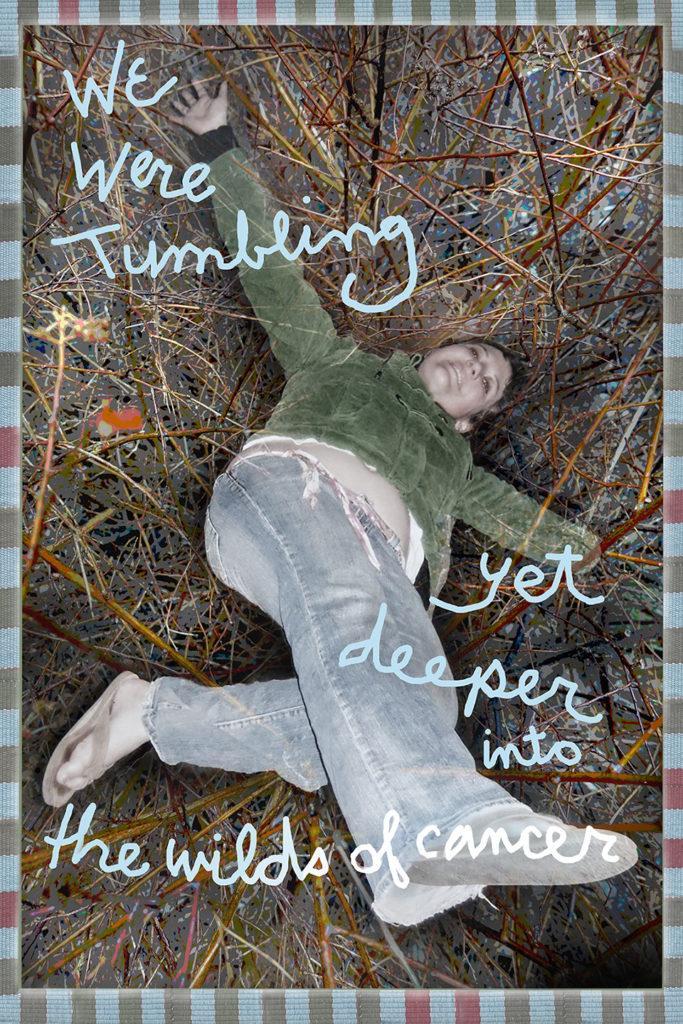

In the fall of 2008, Marika had wanted to hide her scars, the telltale signs of a cancer survivor. Hairless, exhausted, foggy from the chemo—it was not the way she wanted to begin college. But she needed to get on with her life. And I had my teaching job to get back to. The summer that wasn’t, was over. We thought normal was just around the corner, the cancer gone. So we focused on the logistics of her living in a basement dorm room, using a shared bathroom, and being in contact with thirty-five hundred students coming down with countless ailments just when her white blood cell count was due to crash from the chemo. She carried on with her classes wearing headscarves, make-up, and large dangling earrings, pretending to her new friends and teachers that she was not sick. Except to her friend Jake.

“Mom, I met that guy. Jake. The other freshman who has cancer,” she called during the first week. “On Saturday we’re going to Boston to- ”

“Did you go for your blood draw Monday?” I interrupted, meaning to get back to Jake, whom I’d heard about and hoped she would meet.

“Yes,” she barked back.

“Did you tell your instructors you’ll be gone for two weeks? Will they email you the notes and assignments? Are you eating?”

“Mom!” Over the phone, from three hundred miles away, the sound of my name was like gunshot. Retreating, I stifled my barrage and forgot to come back to the topic of Jake.

Shortly after Marika got back to school in Massachusetts, brother Greg transferred from his army base in Washington State to Fort Drum in northern New York, about three hours from Ithaca. He drove home each weekend in less than two. The oncologists did not think Marika would need a bone marrow transplant but Greg, eager to deploy again soon, wanted to have his blood tested to see if he was a match, just in case.

My children had guts. I felt like a wimp next to them. She was fighting for her life with fevers over a hundred-and-four. He was flirting with death in far off deserts filled with improvised explosive devices. And I got on the phone or emailed almost daily to ask if they’d eaten enough protein for breakfast. They were anchored in their real worlds and I was the dizzy planet that orbited light-years off in the vast space around them.

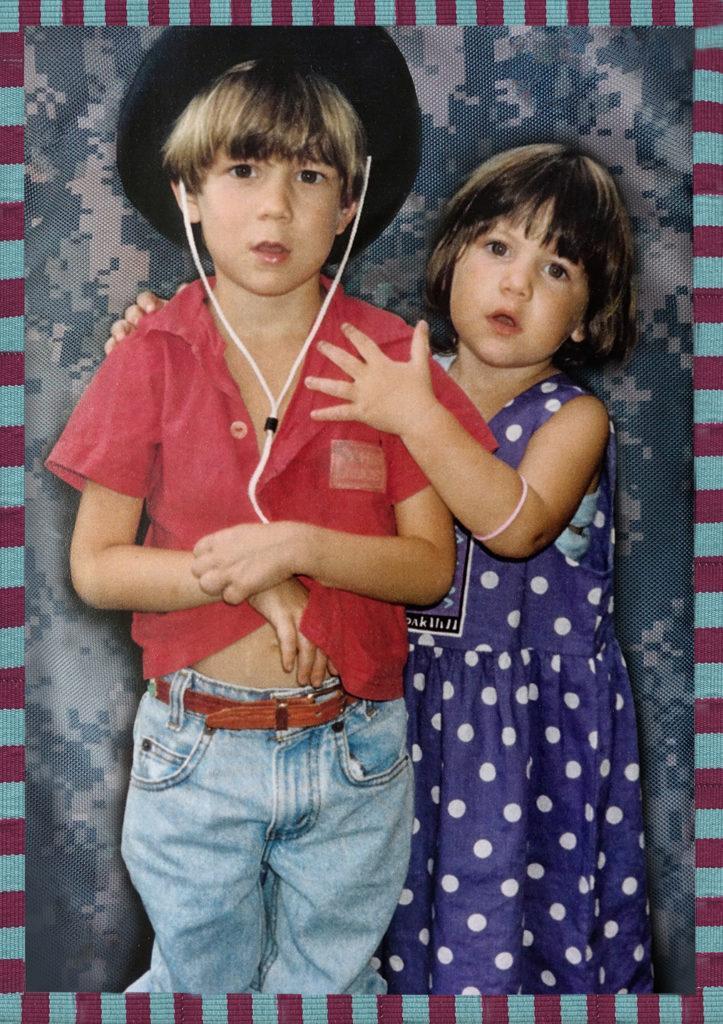

They’d rarely been in agreement until he shipped out to boot camp. He was always a warrior. Or, more precisely, he had learned to fight to hang onto his share of the attention when his sister was born. She would wave her tiny clenched fists in his face when he peered into his old crib to find the sweet playmate he’d been promised. Twenty-two months apart in age, when Marika was three Greg cut off a chunk of her hair and she walloped him. He destroyed her doll; she walloped him again. She adored him but he’d storm into her bedroom late at night, whooping a war cry, and she’d wallop him on the spot. And then Greg would barely contain a gloating grin as she got punished for walloping him. There was constant competition between them.

“One day you two are gonna be best friends,” I’d say and they’d look at me like I was wearing dirty diapers. For many years, Marika was the big strong one, but Greg was fearless. He fought me and his father, his friends and his sister, long before he grew to be six feet tall and was called to Iraq and Afghanistan. As a teenager itching to get out of small town Ithaca, he teased the local cops, tearing through the streets on his bike. When he got his license he tore through town in his father’s truck, or in a girlfriend’s mother’s sedan, ripping up lawns and shearing mailboxes. Through an early-entrance bonus program he entered the army during his last year in high school, and trained in paintball combat with the recruiters on weekends, until he could graduate. Desperate to get going on his career, he was a displaced soldier, a total misfit in the liberal college-town of Ithaca. Marika and I were proud of him, but we worried about the trouble he could get into when he was home, and fought nightmares of worst-case scenarios when he finally deployed.

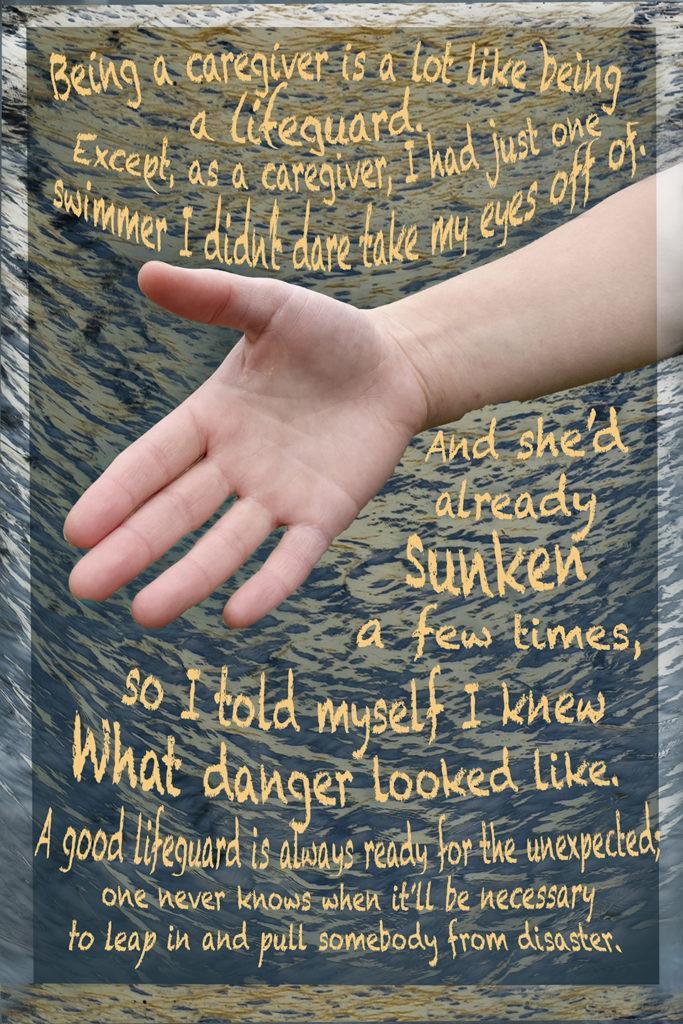

What does it really mean to be a soldier, I wonder? Soldiering, like lifeguarding, involves a lot of standing guard and protecting. Soldiers fight fiercely for causes, often destroying lives in the process. A lifeguard’s main mission is to save lives. Lifeguards stick around in one area, ever watchful to avoid disaster, while soldiers are always saying goodbye and leaving, heading off towards the thick of danger.

Long ago I lived with another soldier, loved him, and so many times watched him go out into the uncertain world. My father. He had been in the army during World War Two and was climbing the ranks in the Civil Air Patrol as I grew up. I’d spend hours following him, observing his carefully coordinated movements. I’d run to the door with the barking dog to welcome him home each evening, and made it my job to be up at six every morning to see my first soldier off to work.

Early one morning the boiler exploded in the musty basement of our Long Island ranch house. My father gathered up his three daughters and our mother into a far bedroom, and then led the fire brigade up and down the stairs to the scene of the disaster where it was not yet clear if the emergency was over. Strong and courageous, he was the one I wanted to be like. So later, whenever it was my turn to face danger, even though I was terrified, I tried to do what I thought my father would do: get tough and let nothing get in my way.

Soldiers tread the shaky ground between life and death. It is not always prudent for soldiers to ponder too closely their proximity to death; it’s more feasible to press forward with the mission at hand. When my son was about to leave for his first deployment, he went to say goodbye to our beloved family friend Andrea, the Montessori School directress.

“Greg, are you prepared to die?” she asked. Maybe it was like a small grenade bursting in his head, giving him something to think about. That’s how it hit me later, as his mother, when I heard about the conversation and tried to imagine how anyone could ask this of a soldier going off to war. That’s Andrea. She’s another lifeguard, caring for young lives in her small corner of the world. But unlike me, she wasn’t afraid to question what she didn’t understand.

“Yes,” Greg had answered her. And later, in Iraq, he missed death by mere minutes, inches, and the luck of being put on the fire squad that entered the building next to the one that was rigged.

No one ever asked me if I was prepared for a child of mine to die. Or I might have joined the Smother Mothers tribe, and clung desperately to all my beautiful soldiers, slowly strangulating the life out of them myself.