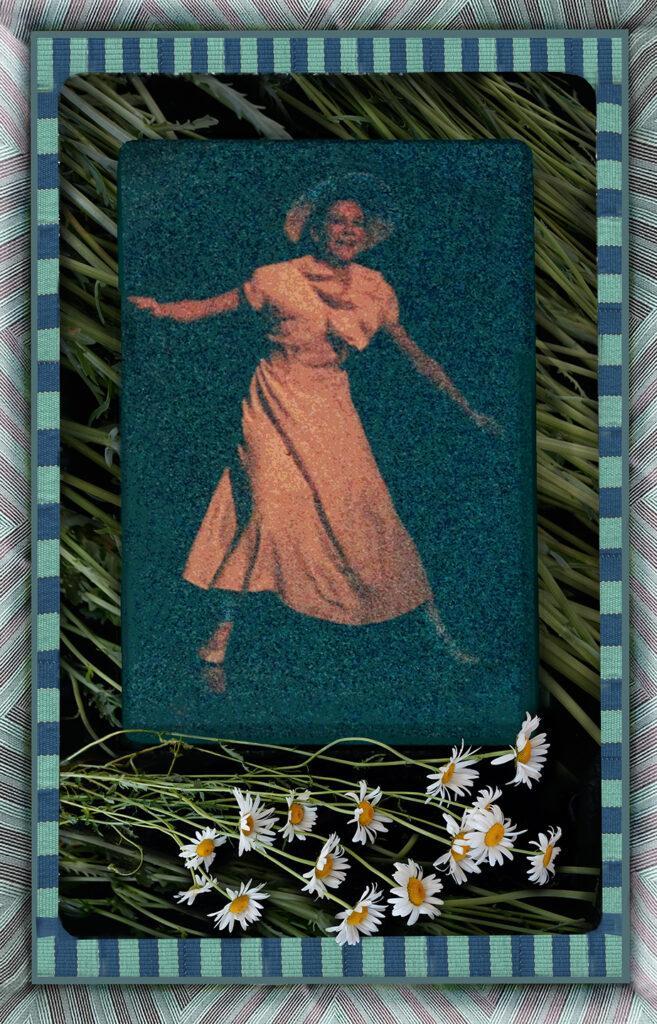

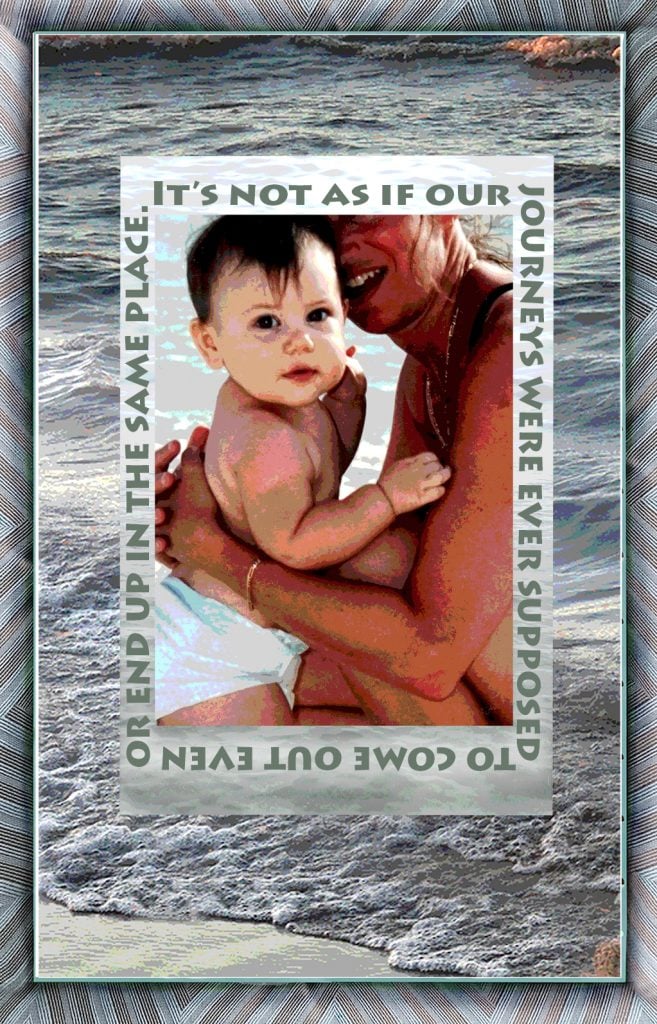

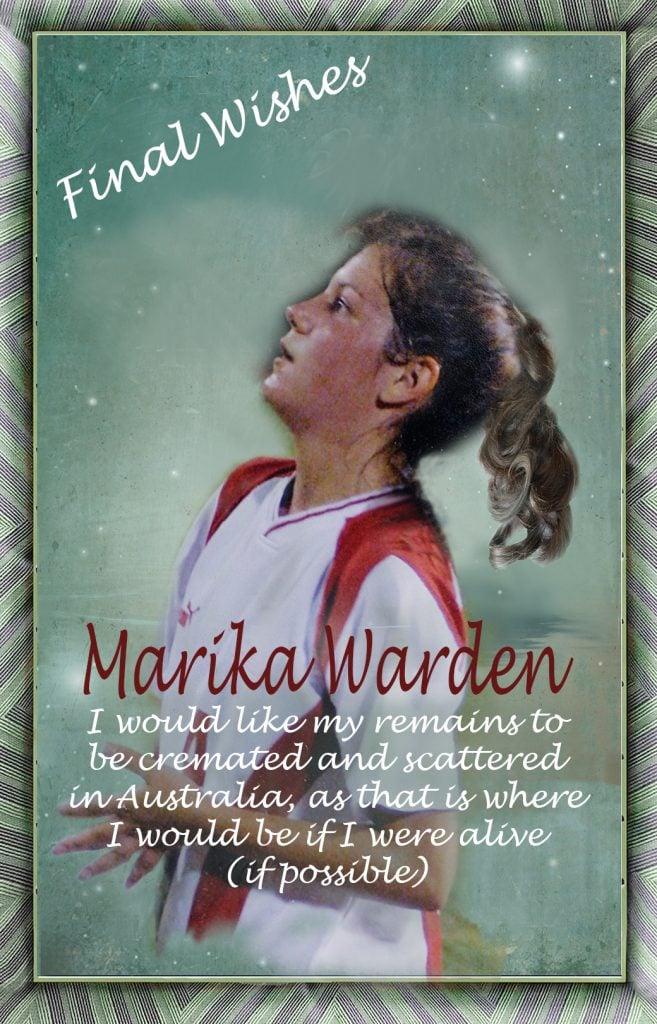

In late July 2011, I bring home the sealed black box containing my daughter’s ashes, and assemble a small altar in the living room, above the TV. Around the box I place photographs, daisies, chocolates, Marika’s stuffed Puppy, and two Lonely Planet Guides to Australia. The first summer without Marika is half over when I finally end my travels. I hadn’t found her anywhere else in the world. The box is where she lives now. Each day I stand before it wishing Marika good morning and goodnight. Her ashes are not just dust. The ashes are her, humming and dancing inside the box, watching me come and go.

With Rachel’s help, I clear out most of Marika’s bedroom in the house. Then, in a reckless determination to purge, I attack the attic, my son’s sprawl of accumulated stuff, and my own closets. I sell off my father’s stamp collection and deposit carloads of clothing and toys at the Salvation Army. It all has to go. The only things I want are Marika’s words. And once they are photo-copied, I send the original journals off with Rachel to give to Marika’s father. Then Rachel and I empty Marika’s bedroom at the apartment she shared with friends.

“What’s up with you?” I ask her. Rachel looks like a wounded animal. “Are you okay?” My eyes are drawn to the silver Tiffany’s necklace she wears, the one Laurie gave Marika for graduation.

“I’m not with my boyfriend anymore,” she says.

“Should I say sorry or congratulations? Well, either way, congratulations. ‘Cause you’re with you.” It’s what I say to anyone who tells me she’s survived a separation and is suddenly single or alone. It’s what I tell myself: You still have you. But I don’t recognize this as a gift yet. I feel I’m only a ghost of the person I was before. And it’s still hard to face people. I’m sure there is whispering and pointing just beyond my earshot and sight. Like last year, at a party, when my friend Andrea nodded discreetly in the direction of an acquaintance, “Do you see that woman? She’s been through hell and back, and she looks it.” I’d regarded the blinking, quivering woman who did indeed look like she’d fallen to Earth from outer space, breaking the sound barrier, her heart, and every moving part of her in the fall. Is that what I look like now? Floundering and crazed?

After Rachel and I bag the last of Marika’s shoes, I wash my hands singing “Happy Birthday” twice to Marika, and consider the strange haunted face in the mirror. Red rheumy eyes stare back. Graying roots jeer at me. Ugh. This has to go too.

Then, in early August, on a Sunday morning hike with Suki and friends, I fall in a slippery stream bed, and break my wrist. Right away I know it’s fractured although it is the first bone I’ve ever broken.

“Go. Get back to enjoying your Sunday,” I tell my friends who take Suki and drop me off at the hospital. “I’ll be fine.” But I am not fine. It’s my first time back at a hospital since Marika died. Waiting alone in the ER, I break down in howls. All the tears I had stuffed away for months each time I bravely faced the world beyond home, come gushing out of me. Marika’s supposed to be here, not me.

And then, as I bumble around the next several weeks in a cast, I suffer all sorts of snags. Mishaps. Glitches. Calamities. I get the flu. I mislay bills and incur late fees. By a hair, I miss hitting a deer on the road. Everything I cook burns. My keys disappear. My house is plagued by deferred maintenance. Skunks move in under my deck, and the pond is overrun with muskrats. I can’t sleep nights. And at the end of September, I get a traffic violation for failing to pull into the far lane when passing a blinking, parked cop car.

“Mom, you’re such a wimp,” I hear. And I know I’ve got to do better. So, I begin to drag myself out of the house and down the hill to the community that loved Marika. I start co-leading Chronic Disease Self-Management Workshops for the Tompkins County Health Department. I join a six-week hospice-sponsored group, Singing Through Your Grief, where mourners are supported as they share stories and sing. CompassionNet, a program serving New York State families of children with life-threatening illnesses, offers to pay for life coaching sessions.

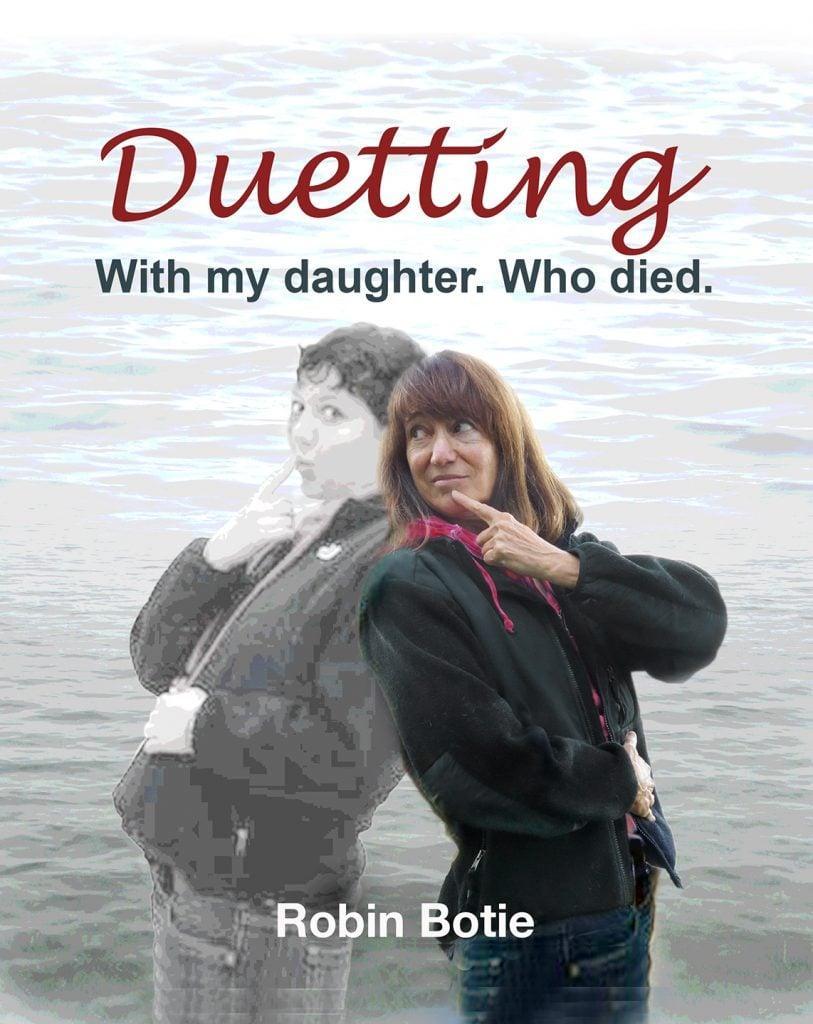

“Why don’t you write a book?” asks my life coach, Marci Solomon.

“I would never,” I say, scrunching up my nose like Marika did when I suggested she wear shoes and socks in winter instead of sandals. But I enjoy writing responses to the questions Marci asks each week. And I eagerly do the homework from the Hospicare singing group.

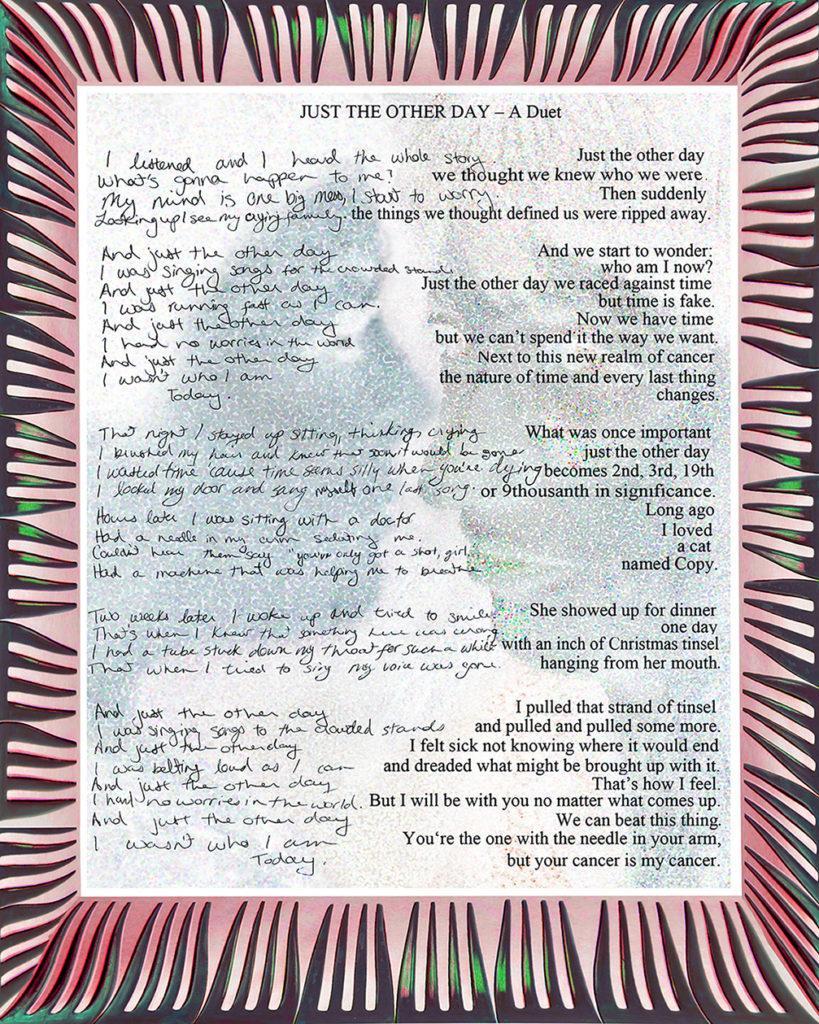

“Your assignment is to pick a prompt from the list and write what you would tell your deceased loved one,” say Jayne Demakos and Kira Lallas, who lead Singing Through Your Grief. At the session that follows I read aloud what I wrote. A reverential silence followed by exuberant praise energizes me like richest chocolate.

“I will write for five hours this week,” I pledge at a Chronic Disease Self-Management workshop. Even the co-leaders are required to make and complete Action Plans, weekly contracts to do something for themselves, and then share their successes or failed attempts at the next meeting. The following week, “I will write for ten hours.”

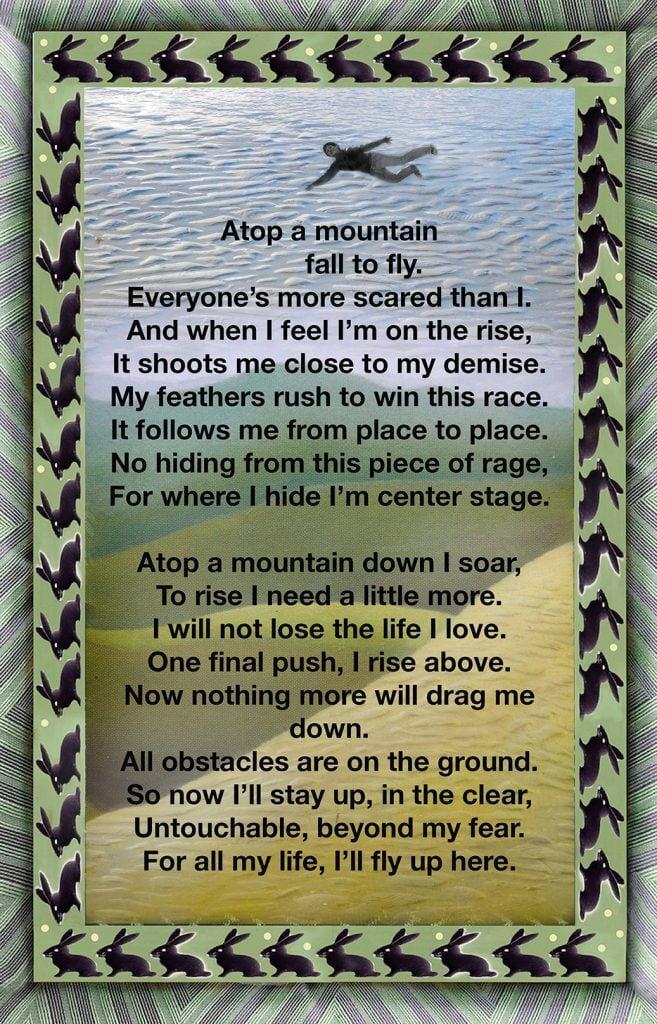

It was just letters to Marika at first. Like on the TV game show Jeopardy, I teased out questions from her poems and songs, questions I wish I’d asked during our time together. What’s it like to be twenty and have cancer? What do you fear? How does cancer affect your relationships? … Memories swell up inside me. Words churn in my head. And when all the commotion is captured onto paper, I experience a thawing, a lightening. When I read aloud what I wrote, it becomes part of me. It makes me feel stronger. And it makes me sure this is not something I want to do on my own.

“Hey, Rachel, I’m writing a book,” I say over the phone. Then I call a dozen other friends. “I have an idea,” I say. “I’ve been writing a book and want to test it out. I want to do a series of simple dinners where I read aloud. Chapter by chapter, as I write. I’m calling these dinners ‘Feed and Reads.’ Would you come?”

It is so exciting to enlist listeners. With thirteen positive responses I begin two small groups that will fuel my energies over the next year with their kind and brave commitment. December starts out dreary. But I write for hours every day. Often by candlelight. For Marika, and now for the women who will gather together to hear me. Addicted to light, I line the driveway with solar-powered garden torches. I frame the mudroom door with rows of red mini-lights, and plant battery-operated plastic candlesticks in the windows up and down the house. I buy hundred-watt bulbs and full-spectrum therapy lamps to write by. Sweet light blossoms all around me, breaking the darkness as I write. Warm welcoming lights brighten the winter nights, the empty house, the long lonely driveway, and my dark heart. They beckon, they plead: come to me, come home.