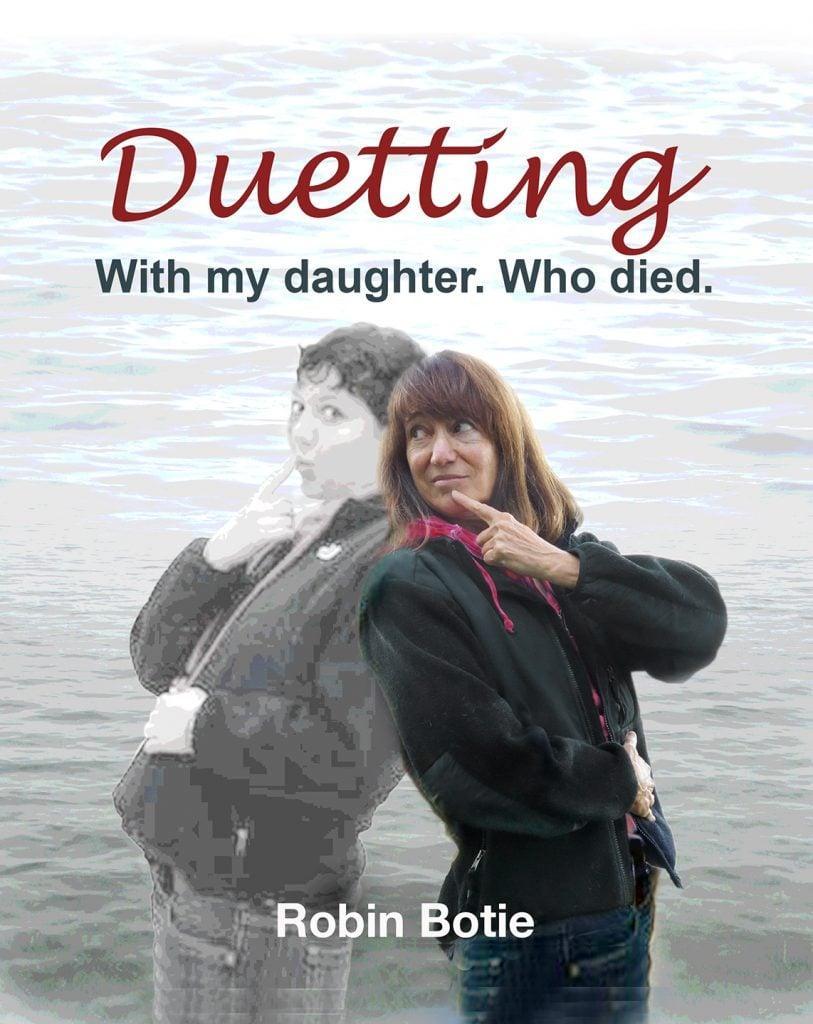

When your life gets completely obliterated you can chuck it or you can go on, wailing and whimpering as you plant one foot forward in front of the other. I don’t know which is harder. In the thick of loss it’s not like you can recognize any options.

In March 2012, on the first anniversary of my daughter’s death, people are sending me mixed messages: it’s time to get on with your life; give yourself time to heal; get over it; this will be with you forever. It embarrasses me that I’m not employed yet. I had allowed myself the year off. But now my mother’s hints about getting a job have turned into sharp jabs that leave me gnawing at my cuticles. There are no jobs in Ithaca, not for me anyway. I don’t even know who I am anymore or what I can do. Marika’s been gone a whole year, and all I want is to stay home and write at my table in the corner of the house, overlooking the pond where the geese are back trying to nest again.

They’re early this year. Every year the same two geese sit in the same place and build the same measly little nest. Some years they even get to hatch their eggs before a raccoon or woodchuck claims them. Marika and I often watched a bevy of baby geese paddling in the pond between their parents, or waddling on the bank. One always toddled way behind or in the wrong direction. We woke many mornings to squawking and splashing as the parents tried to ward off other overtaking geese. And inevitably, every day, there’d be one less egg or one more baby goose gone, and then another gone, and another, until there were no baby geese left. Then the father would fly off and the mother would wander back and forth along the pond bank, picking at the pitiful remains of the nest. And I can tell you for sure that geese cry; it’s one of the saddest songs I’ve ever heard. A sound, something like sobbing, sighing, heaving, and honking—all at once— fills the sky begging, “Why on earth?” and “What’s next?” and “How?”

“Did you hear from Pat?” I call Rachel. Pat was Marika’s Australian boyfriend. Rachel has his address, email, and phone number from the shoebox where she’d found the final wishes and a sealed letter to be sent to him upon Marika’s death.

“He said he’s expecting to hear from you.”

“Do I have the right address?” I’d emailed Pat twice already and not gotten a response. None of the Australian connections have replied. This is not turning out to be the trip I’d imagined. I wanted to meet up with people. I’d hoped to make it a family pilgrimage with my mother and Laurie, but my mother couldn’t go. And now, because of Laurie’s recent knee replacement, we need to rent a car to get around, forcing me to alter the trip again. Laurie calls at the last minute.

“Robin, I’m sorry. My knee is infected,” she says. There is a long pause. I wait. For the inevitable. But she wants me to fish it out of her. Laurie must really feel bad; I usually can’t shut her up to squeeze in a word of my own.

“You’re not going?” I say, knowing already and seeing only stunning white light.

“It’s just not going to work for me. I’m sorry. I really wish I could go,” she says. And I try not to panic or say anything to make her feel worse. So. Why on earth? What’s next? And how?

The day before I am to leave for Australia. Greg carries his rifle down the stairs, and together we traipse outside and around the pond to shoot the Heart Drive from Marika’s old computer. It bothers me that the box of Marika’s life-before-cancer could get swallowed up and lost forever in Greg’s vast accumulation of stuff upstairs. The Staples tech had said to destroy it. Destroying is a job for my warrior son; putting the pieces away in the right place is what I do. This is the last item on my list of things to take care of before the trip. And Greg may be called to his new job in Afghanistan before I get back. So we place the little black box at the base of the willow tree that still stands despite being shot at for the past year.

BAM! LikeBAM! He shoots. All the homework assignments, Marika’s pre-cancer concerns, the girl-life contained in that small black box, LikeBAM! The long-gone girl who preceded the almost-adult daughter I miss, BAM! BAM! No fanfare. No fireworks. No explosion of computer chips or chorus of hallelujahs. Just two surprised geese taking off fast from the pond at the first of the five shots. I hold back my tears as we examine the remains of the box. Satisfied that the contents are indeed destroyed, we bury it deep into a muskrat hole by our feet. This is Marika’s pond. Part of her will always be with it. I curl my lips around quivering teeth, and clamp down hard.

Back inside the house my friend Liz types away on the computer. Greg disappears upstairs, and I hover nervously over Liz as she fidgets with my iPad, and enters the email addresses of the women who have been gathering month after month to hear what I’ve been writing. Time is running out as I scour my contacts and my memory for all the strong women in my life, to add them to the list.

“How am I going to do this?” I ask Liz.

“You go to your gmail account on your iPad, you open up this email, then you –”

“No, I mean the whole thing. Tomorrow. This trip,” I say. “It isn’t right. What on earth am I doing going to Australia—alone—to spread my daughter’s ashes?”