In late September 2012, at a campfire with musicians, a friend’s daughter tends the fire. Bent low to the ground, she blows at the coals until waves of flame dance up and embers riddle the air in fireworks of crackling jewels. Her every movement matches the music, and I sit in a lawn-chair, watching, mesmerized. When the fire is really roaring and the fiddles whinny at a feverish pitch, the young woman steps up barefoot on the rocks that circle the campfire. She tiptoes around the fire gracefully from rock to rock as the firelight plays on her face.

“Marika, you’re too close to the fire.” That’s what’s about to burst from my mouth as I watch this girl-woman. I catch myself just before toppling off the edge of my seat.

No one is like Marika. My friends’ daughters don’t really remind me of her. But late the next day, as I stroll over crack-dry leaves in the driveway, there’s the sound of an approaching car crunching gravel, and I feel a hopping in my heart. For seconds, I hear the old dented Toyota pulling up, music blasting, leaves flying behind it. Marika would show up suddenly like this. Just before dinnertime. She’d tumble out of the car carrying a full laundry bag, with Suki pulling at her leash. A cool smoke-tinged breeze brushes by. My deepest sadness is triggered by these sounds and smells. Marika had come to me like this last autumn too. And it had taken a whole winter to creep up out of the dark depths of despair.

“You don’t magically recover in a year’s time,” says Meg, my CompassionNet social worker who still keeps tabs on me, a year and a half after Marika’s death.

“But I’m tired of these triggers wrenching my emotions, at being accident-prone and making poor choices. Forgetting. Falling. Losing things. Breaking things,” I tell her. “Missing appointments was something someone else always did. I can’t even dress myself right. I used to be a teacher. I was a lifeguard. I took care of other people’s children. Except for childbirth, I was never in a hospital for my own care until this past year. Now I’ve broken a wrist, my nose, and two toes. My eyes are cried permanently bloodshot. I had vertigo last week. And Lyme disease. My sister wants me tested for some kind of neurological impairment. Is this how it’s always going to be from now on?”

“Take care of yourself,” Meg says, her brows twisting in opposite directions off her face. And I think, Yeah, I’m my own lifeguard now.

Sometime after, Rachel phones, “You hafta meet my new girlfriend.”

“Girlfriend?” I’m caught off guard. Why would she want me to meet her new friend? This must be a really special new friend, I think. And then I finally meet up with them, Rachel and her Girlfriend. Not a boyfriend this time. I mull it over and over, trying to get comfortable with an ever-changing Rachel.

These days I’m desperate to have something stay the same. My whole life has changed. It seems like to live is to change, and I’ve been fighting it. And I thought that Marika, being dead, would not change. I’m finally getting to know who she really was, but even dead—and after a year and a half I can finally say ‘she is dead’—she is changing too. Or, maybe it’s our relationship that’s changed. Marika—her ghost—is no longer fighting me. I noticed that. Somehow, now, she’s cheering me on.

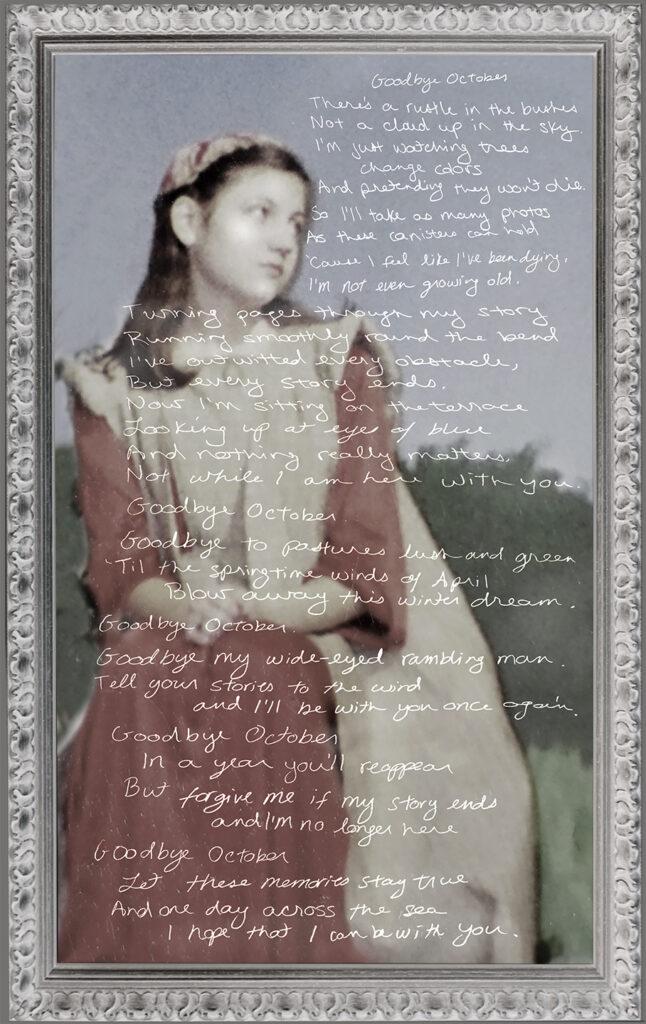

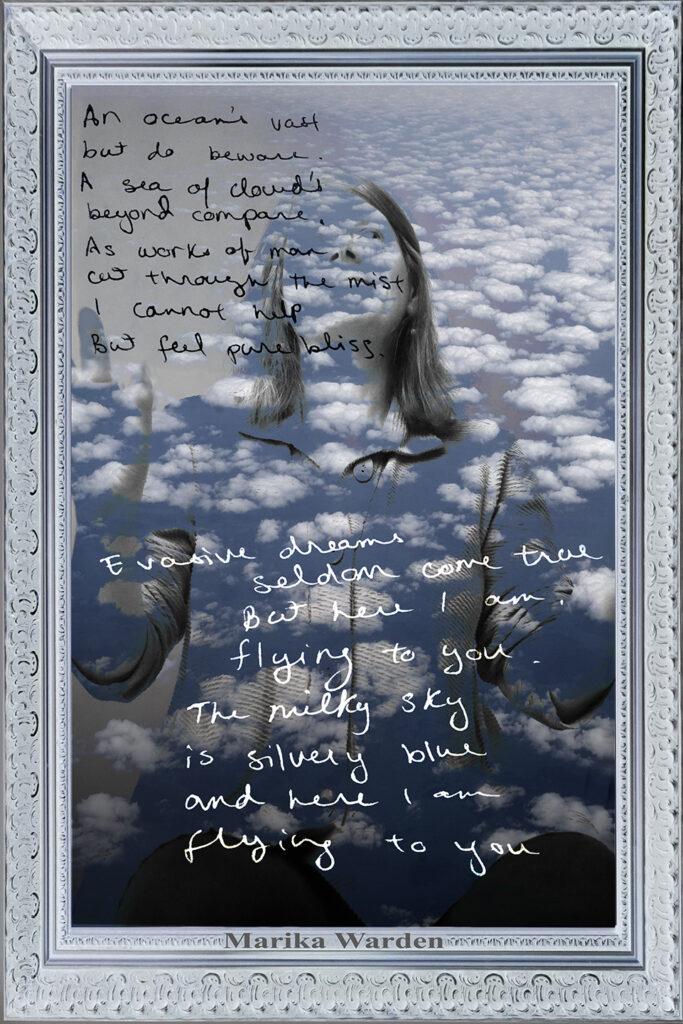

“Always, Marika,” she used to sign her letters, notes to friends, emails, … everything. Was that a plea to remember her or her pledge to always be there? Was it a wink at immortality? Or was it simply a pretty word that could sit next to one’s signature instead of ‘sincerely’ or ‘yours truly,’ without too much thought behind it?

Who dares to say “Always” in a world plagued by climate change and ozone layer depletion? How could she sign something “Always” with deadly global viruses, nuclear weapons proliferation, water pollution, terrorism, financial meltdowns, and ecological destruction all over the planet? With freak accidents, madmen with guns, asteroid impacts? With cancer. A million things can go wrong. It takes just one to end your “Always.” Always is every time, at all times and for all time. Forever. Continually, repeatedly, in any case and without end. Always is the sun rising and setting, hopefully. Time. Space. Rocks, maybe. Even earth may not be around for always.

I will not be around for always.

Shortly after Marika died I found a small gold ring in her room. In many cultures a ring, an unbroken circle, symbolizes infinity and undying love. However, this ring is one of those adjustable bands where the ends don’t meet. As soon as I put it on, I knew it would snag on something someday and fall off. Sooner or later I will lose it. But I’ll wear Marika’s ring as long as I have it; when it’s gone I won’t regret not tucking it away in a box or someplace safe. Can I treat people this way? Like they are not forever? Can I treat my own life this way, like it’s not for always? Marika lived like she had only an hour left. How differently might we all live if we had expiration dates stamped on us like cartons of milk?