At Bang’s Funeral Home, we discuss the ashes. Her father wants them. He says he will buy a nice urn. Then he starts talking about dividing the ashes between us.

At Bang’s Funeral Home, we discuss the ashes. Her father wants them. He says he will buy a nice urn. Then he starts talking about dividing the ashes between us.

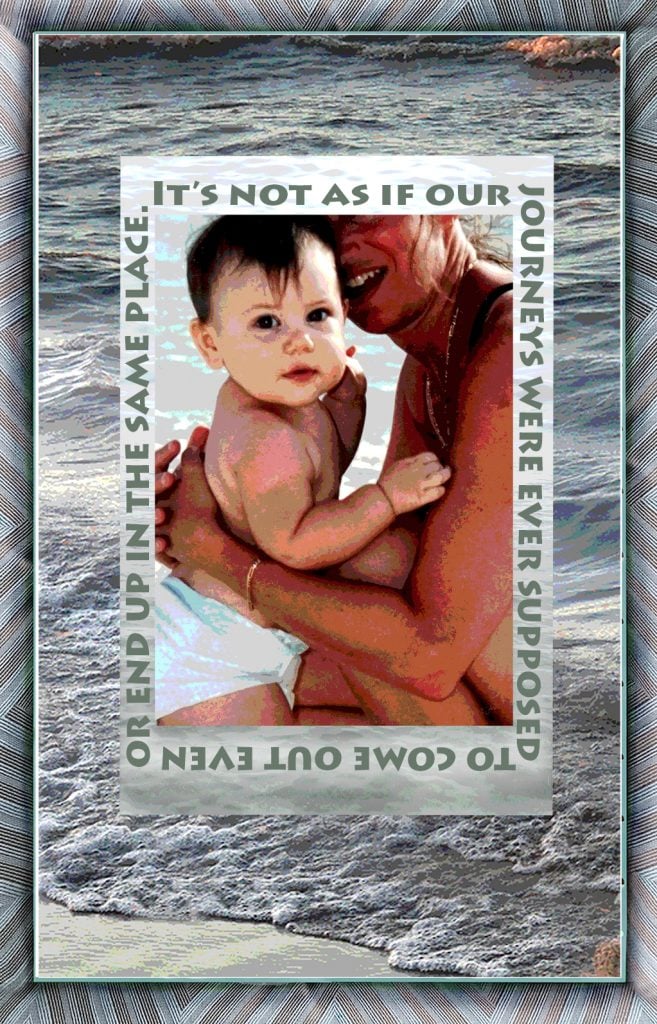

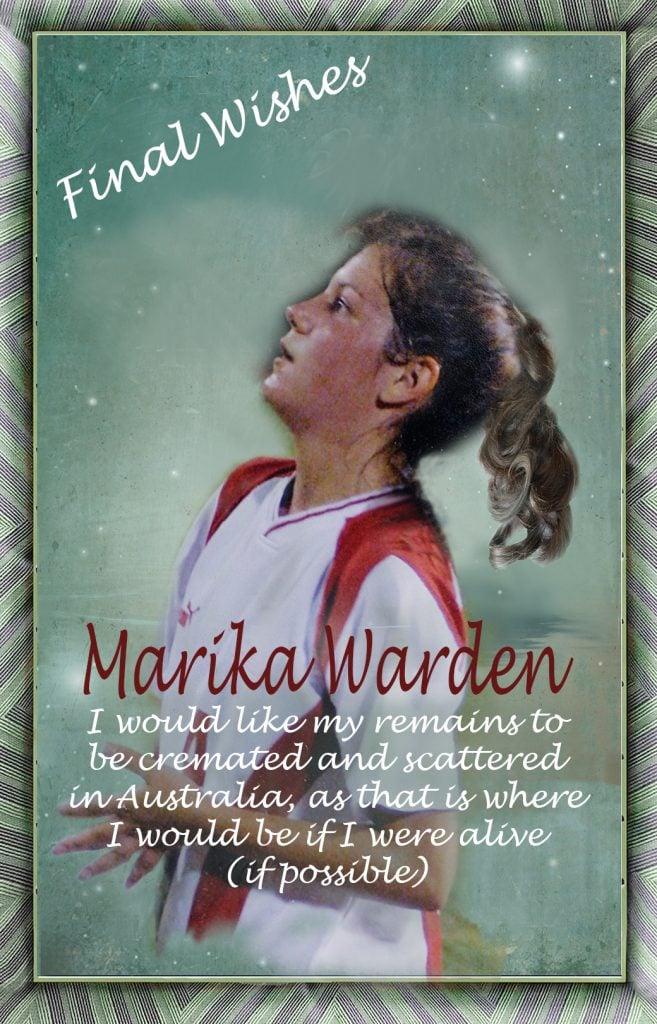

“No. Don’t split her up,” I beg. “You can keep her ashes. Whoever goes to Australia first will take them.” That’s how we leave it. I assume he and his wife will be the ones to go to Australia anyway. That’s okay. I don’t need my daughter’s ashes. I have her words.

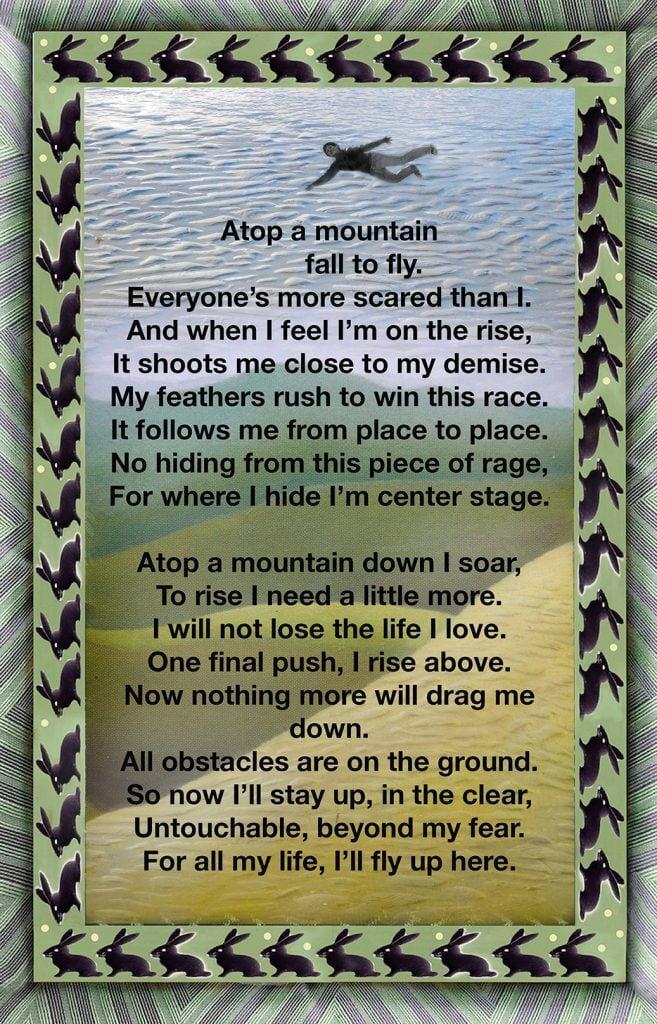

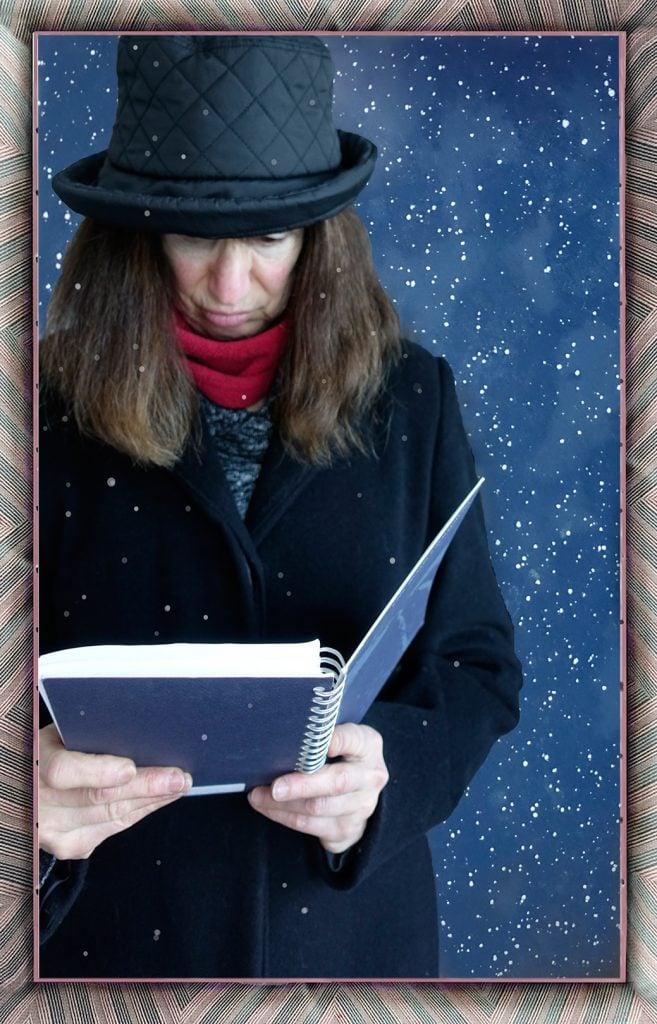

Family members and a couple of Marika’s best friends gather in a back room at Bangs for a brief service before the calling hours begin. My friend Andrea, directress of the Montessori school my children attended, hands out DVDs of Marika singing “Over the Rainbow” at a school anniversary celebration ten months ago. When Marika was barely six, Andrea had given her the leading role in Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Coat knowing she would be able to sing the songs, if not deliver the lines. Marika went on to star in the school’s production of The Wizard of Oz, and music became an important part of her life. I hold the DVD of her return to the Montessori community as a star having conquered cancer. Marika’s friend Rachel holds a life-sized portrait of Marika. My mother and youngest sister Wendy hold Laurie, my other sister, who looks like she’s been shot. The small group is silent as I read Marika’s poem, “Atop a Mountain,” clutching the journal to keep from crying. Marika would want people to hear it, I remind myself. I must not sob her poem away.

The calling hours begin. It’s my last chance to stand up for her. To stand guard. I will be a soldier. A rock, solid to the core. Soldiers go to funerals for their fallen comrades all the time and never break down in tears, I tell myself. Or maybe they do and I’ve been turning my head. I stand with my twenty-two-year-old soldier son who is no stranger to funerals. He arranged Marika’s.

Most of the people in the procession somehow know better than to try to hug him. Greg looks lost, and brittle like he might crack if you got too close. A man of few words even during the jolliest of times, he nods, avoiding the faces, watching the floor from his six feet up. He stays by me the whole five hours. Be strong next to him, I tell myself. But my tears are nowhere near. I’m too awed by the endless crowd.

It was supposed to be only three hours. But dripping wet people keep filing in. They wait outside in the rain in a long line that winds around the block, trudges up the stairs, and circles the porch of the funeral home. Inside, they pass the hushed room where my mother and sisters sit. They enter the lively space where members of Marika’s father’s and stepmother’s families are clustered, and finally reach the inner chamber where Greg and I are stationed with the stuffed Puppy and life-sized portrait. And I can’t stop thinking how courageous all these people are, waiting to face a shell-shocked family, a soldier saying goodbye to his only sibling, and a heartbroken mother who lost half her world.

“Are you doin’ okay?” Rachel bends from her high-heeled six feet to hug me when the visitors are gone. Her eye makeup has smeared, but otherwise she looks like she’s held up.

“Tired,” I say. It’s what Marika might have said—one word to someone who cares, but doesn’t care if I don’t feel like talking.

Months after the calling hours, Bang’s Funeral Home phones me. What do I want done with Marika’s ashes? Horrified to hear she’s still at Bangs, I drop what I’m doing and fly sobbing down the hill to bring her home.

“I’ve got Marika’s ashes. I’m sorry,” I leave a message on her father’s phone. “You can have them anytime you want. But her words—she wanted to be scattered in Australia. So I can’t just leave her abandoned in Bangs’ basement.”

That’s when I make a promise—Australia. That’s when I know I’ll be the one to go.