I’m an expert on fear. Long ago I defined two categories, based on how hard it hit: the immediate mind-gripping terror where one may respond quickly and with focus; and the kind of fear that festers deep inside, an ache that slowly gnaws away at one’s heart and gut. Fear is what fuels most of my functioning. It’s also what immobilizes me. I’ve learned to mostly tame it by looking ahead, asking, “What’s next?”

At the end of July 2012 on Long Island, after moving from my cousin’s place to the Ronald MacDonald House, and spending weeks wandering the halls at the North Shore Medical Center, my daughter and I were permitted to go home. We would need to make weekly trips back to Long Island. Even so, the prospect of having several days a week in Ithaca for whatever summer was left, cheered us. But shortly after arriving home, Marika developed chills and fever. We dashed to our local hospital where she was pumped with antibiotics, and then we were sent back to Long Island. Marika’s leukemic white blood cell count had climbed high off the charts. Afraid of a repeat of the syndrome that put her into respiratory failure and nearly killed her the first summer of cancer, the new Long Island team gave her a dose of a Phase Three experimental drug that was only made available to patients who had no choices left. Mylotarg was called a “magic bullet.” Unlike chemo drugs that kill or damage everything, the Bullet targeted only leukemia cells for destruction, and left the liver, kidneys, and other organs intact.

The Bullet worked for Marika in just one dose. But the trouble with the Bullet was its frequent side effect, horribly high fever. Fever that surged after a day of hibernation. Fever that was impossible to tell if it was from the Bullet or from some hidden, lurking infection. Getting close to summer’s end, Marika desperately wanted to be home where most of her friends were preparing to leave for their colleges. We both yearned to go home. Fever was the only thing holding us back.

When she was free from fever for two days, we left Long Island. It was a Friday afternoon, when everyone else was fleeing for the weekend. We slowly inched our way out as the Brit in the new GPS dragged us through the scenic route of New York City. We were stuck for hours in traffic. In the heat. Sitting in the passenger seat, excited to be going home, Marika was talking to me once again. She was pink. Maybe too pink in the air-conditioned car. Between us a brown paper bag held her meds and a thermometer. Finally out of traffic, we approached the more remote parts of Pennsylvania, and stopped for dinner.

“I’ve got a fever again,” Marika announced, removing the thermometer that chirped the now familiar alarm of four sets of three high beeps. She took a dose of Tylenol, and we downed hamburgers and cold drinks at MacDonalds, ordering extra drinks for the road. She took her temperature again, and drank another icy diet coke as I started up the car.

“Mom, it’s up. It’s a hundred-two point nine now.”

“We’re in the middle of nowhere,” I said. The single server at MacDonalds had been unable to help locate a hospital, so we got back on the road to Scranton. Marika checked her temp every ten minutes and toyed with the GPS as I drove. One hundred-three, she whimpered. I think I began to pray then.

“Mom, a hundred-three point four.”

“Are you okay?” I fixed my eyes on the road and heard my own voice getting higher.

“I’m okay,” she said.

“There’s a blue hospital sign. The blue H,” I pointed out. We drove on and on and there was no other sign. It was dusk and it was getting hard to see. I almost ran a stop sign looking for anything that resembled a hospital. Please help us. Someone. Where’s the darn hospital?

“A hundred-four, Mom.”

“Okay, another blue H, I think this is it, can you read that sign?” A one-way street and hidden entrance to a full parking lot, “This doesn’t look like a hospital. Is it? Yeah. I’m gonna drop you off at the emergency entrance.”

“No! I can wait. I’m okay,” she implored.

“Mareek–I have to park in the garage, way down the road.”

“I’m not getting out,” she hollered. So I parked illegally, as close as I dared, and together we headed into the emergency room.

“This is a cancer patient on two trial drugs with a hundred-four fever,” I screamed to the woman who seemed too calm behind the glass window at the emergency check-in. Marika was looking very gray now that she was on her feet. Someone shoved her into a wheelchair and took off with her, and I ran to keep up as they wheeled down endless halls and around corners of the strange single-story building that was unlike any of the hospitals we’d frequented the past two years. What kind of hospital was this? Now that we were back in a hospital, a part of me believed we were safe, or that her safety was out of my hands. So then the second type of fear, the gnawing, festering fear-ache, took over. It had sat heavily in the back of my mind ever since I’d been given the papers, in triplicate, labeled ‘Healthcare Proxy.’

Marika had first asked Rachel, and Rachel, knowing what it was, had turned her down. I was Marika’s second choice. Though I did not fully understand what the document meant, it meant everything to me to have been chosen over her father. I had never really considered the day I’d actually have to represent Marika or guess her wishes. But now we were in a strange hospital somewhere outside of Scranton, and Marika was burning up. I unfolded and refolded the piece of paper that lived in the bottom of my tiny purse. Was this going to be the night? Would I have to make life and death decisions for her? Tonight?

At two in the morning, when the fever had died somewhat, after tons of tests and our promise to go straight to our local Cayuga Medical Center, we were released.

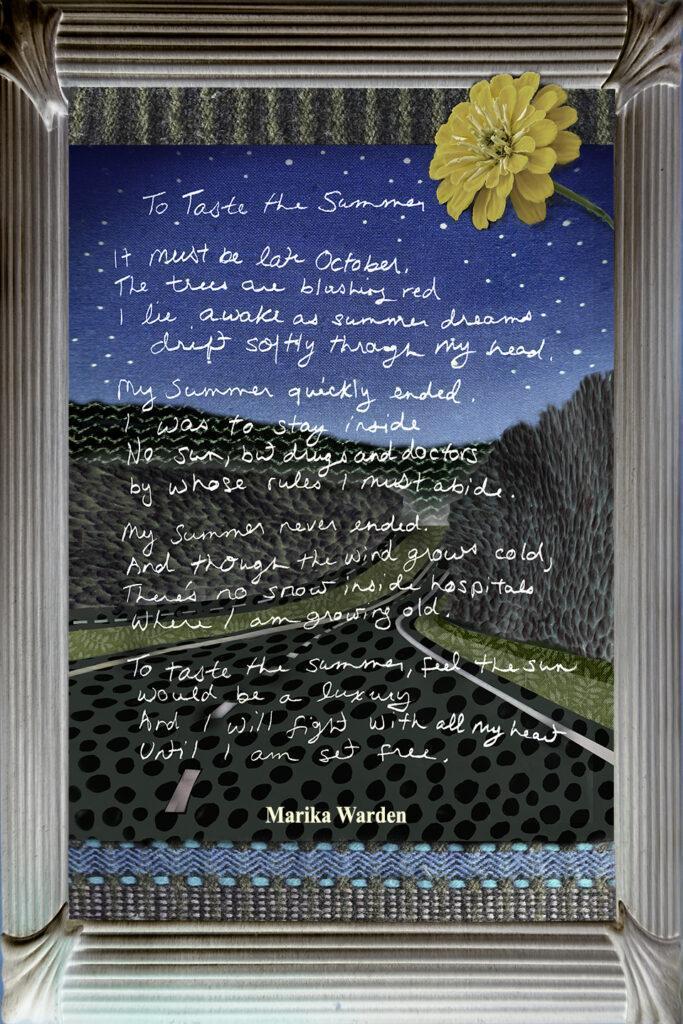

Driving in the dim hours before dawn, I was wide-awake. Something had changed around us. My heart was no longer pounding but I was acutely aware of my daughter as a time-ticking catastrophe. Out the windshield, the sky was a vast ocean over the black hills scooting by. Stars shone above the deserted highway that wound toward home. The world was frighteningly beautiful. Quiet. Peaceful. And in the car, on that almost-last night in August, riding side by side the final two hours to home, Marika and I shared brief bits of conversation, too drained to keep up our usual guarded disconnection.

“I’m gonna take a road trip next summer, with a girl I met in Australia,” she said. “We’re gonna start out in Boston and visit Laurie and my friends at Clark.”

“Neat,” I said. “You think you’ll wanna try to do camp again?”

“This is before camp starts,” she said, “Yeah.”

“Well, this summer’s done.” My eyes widened, taking in the shadowy landscape as I drove. We were planning, considering, “What’s next?” and didn’t know—we had no clue—this would be Marika’s last summer. I said, “Next year we’re gonna have a real summer. No hospitals or cancer centers.”