I hold my daughter’s ponytail to my nose and sniff, then slip it back into the bag, and hurry off to the funeral home where I give it to her father.

I hold my daughter’s ponytail to my nose and sniff, then slip it back into the bag, and hurry off to the funeral home where I give it to her father.

“So you can visit her anytime you want,” I tell him.

Writing would become my way to visit my dead daughter.

But writing the story that pulverizes your whole world is like becoming a lifeguard when you’re terrified of drowning. I’ve done both though neither was ever in my plans. At the age of fifty, to afford sending my children to summer camps, I became a hiking counselor at Camp Scatico in Elizaville, New York, never expecting they would train me to be a lifeguard. Afraid of going underwater, it took all my courage to pass the part of the lifeguard test that required diving into deep water for bricks. Diving into my worst fears turned out to be good training for what was to come.

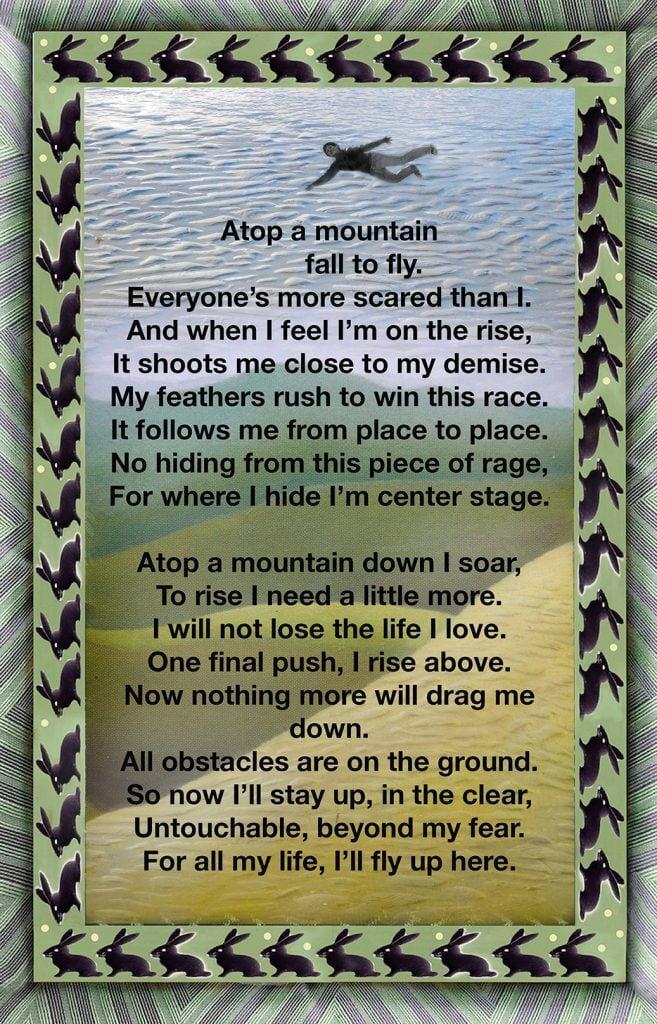

I never wanted to be a writer. The day my daughter died I sank, and then got my life handed back to me, unrecognizable, like I’d picked up someone else’s clothes at the cleaners. Then suddenly, I start writing a long letter to my daughter. Writing jolts memories. It dredges up painful debris. Alternately I sink and swim. I scramble up from great depths, cradling bricks in my arms, in search of the surface so I can breathe again. I let loose the bricks, one by one, on the pages I write.

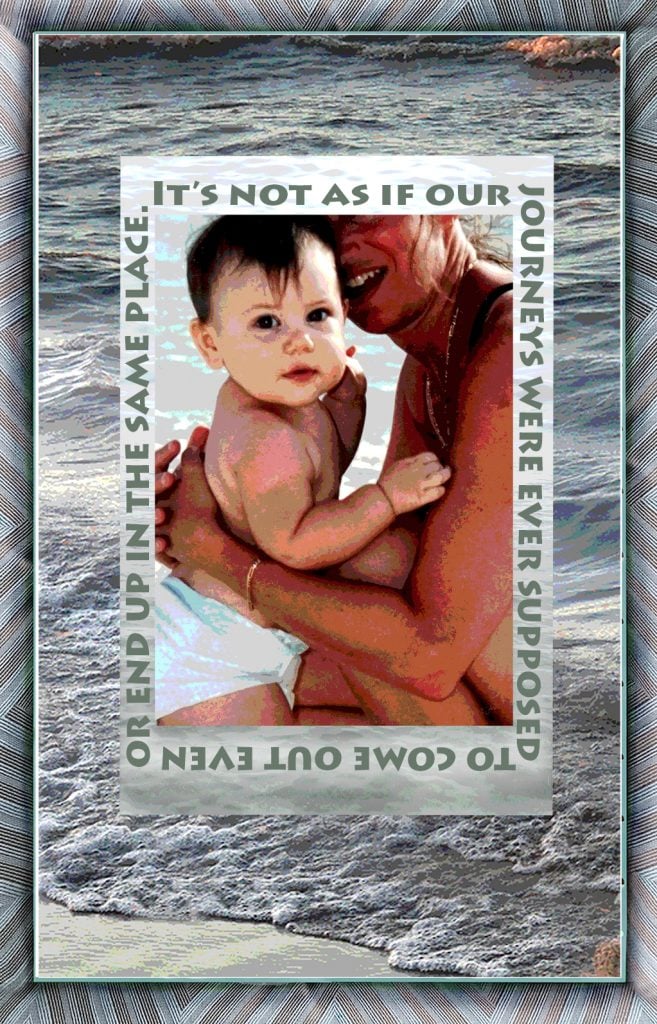

In desperation one day, six months after I sank like a boulder dropped in water, I wanted to duet with my daughter. Too late, you can’t have a duet with a dead person. Someone who’d had her own heart broken told me this when I showed her the letter. I’d poured my heart out into that one long letter, for months, filling it with I’m-sorries, pleadings, and promises: When your tide broke, mine did too. Waves crashed over us. As they washed back out to sea, I was left alone with the sand seeping out between my grasping toes. Somehow, I am still here. So I will tell the story of our broken tides. I will cherish the words you left. Where your words and my words sit on a page together, we will have our duet.

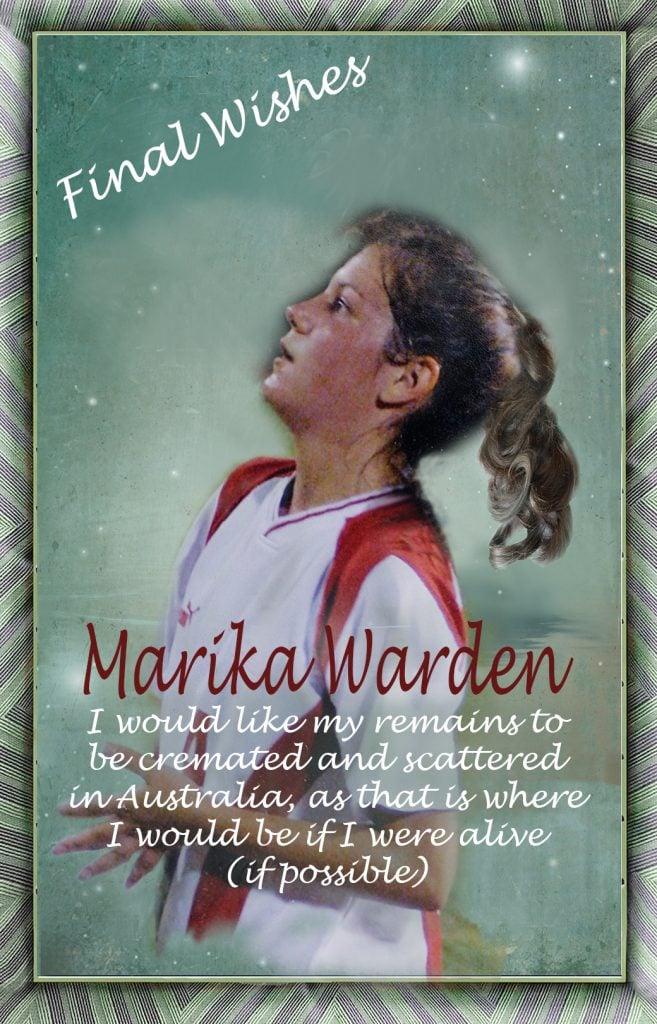

I didn’t know about Marika’s poems until she was gone. If I couldn’t have a duet, at least I could riff off her words until I had a song of my own. So I put the poems, her side of what happened, in the telling of our journey as it unfolded. Then I responded to her words. What did I know about writing? I’m the one who drew and painted. But everything is changed now.

So I write to own what happened. She died. I let her die. To own this is to grow beyond it. I write so that someday I can look at a rainbow again or be hugged without crying my eyes bloodshot.

I write because she wrote. She left behind a brand new, otherwise empty journal with a single poem on the first page. In the bare pages that followed, Marika beckoned me to continue. No. She dared me to carry on.

And mostly I write to separate, in my mind, her story from my story. Because, before her death I was my biggest and bravest self as my daughter’s lifeguard. Before March 2011, my life was all about holding on and keeping her safe. Even as she fought to be free.

Eventually most mothers watch their children go off on their own. There are two stories as each one’s life takes its own direction. Two stories. They wend and wind. Tangling up at times. And then, unraveling. It’s not as if our two journeys were ever supposed to come out even or end up in the same place. A mother is lucky these days if her path intersects with her grown daughter’s for an occasional birthday or Thanksgiving. If a mother pines an hour or so each time her child leaves home, she is fortunate. One more countless sweet sorrow that is not forever. In a heartbeat, I’d give anything to have this be our parting rather than what we got.

Still. Separation was complicated enough before Marika died. From her earliest years on I tiptoed the tightrope between keeping her happy and keeping her safe. Regularly I’d hobble off, wounded, exhausted. But I always came bounding back. I was her least favorite person. But she—she lit up my life. Now I’m left to resolve the questions: Where is she now? Whose life am I guarding? Who am I, if not her mother? And how do I live without her?

Right away, the old mother was drawn to the girl at the end of the table who sat clutching a stuffed animal, her mascaraed eyes staring straight ahead.

Right away, the old mother was drawn to the girl at the end of the table who sat clutching a stuffed animal, her mascaraed eyes staring straight ahead.