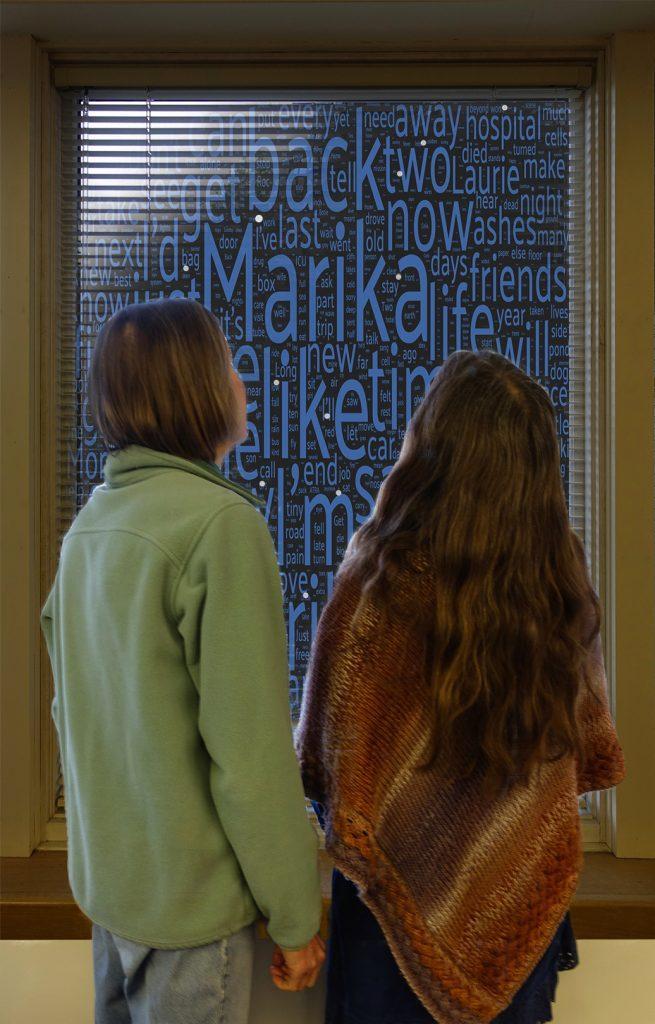

One night in Massachusetts, my sister Laurie and I watch the stars. Then she takes me to Marika’s Facebook page. There we find love letters, poems, stunned friends from all over pouring their hearts out to Marika through the internet. One friend touches another through words that ripple outward, beckoning to an aunt and a mother huddled over a laptop like it’s a window to another world. Invisible webs stretch among us all. So this is what Facebook is, I think. I cast her name out into cyberspace: Marika Joy Warden, who are you and where have you been? Words radiate from my fingertips tapping on plastic. My plea rains over all the planet before waves of warmth come back to me.

One night in Massachusetts, my sister Laurie and I watch the stars. Then she takes me to Marika’s Facebook page. There we find love letters, poems, stunned friends from all over pouring their hearts out to Marika through the internet. One friend touches another through words that ripple outward, beckoning to an aunt and a mother huddled over a laptop like it’s a window to another world. Invisible webs stretch among us all. So this is what Facebook is, I think. I cast her name out into cyberspace: Marika Joy Warden, who are you and where have you been? Words radiate from my fingertips tapping on plastic. My plea rains over all the planet before waves of warmth come back to me.

On the screen, I see familiar names and photos of children I once knew, now grown. For many of them, Marika’s was their first death. For many more, it was the first death of someone their own age. A few had phoned me on her birthday and on Mothers’ Day. They are traveling or still at college. In all corners of the world, they are getting on with their lives.

I am not getting on. I want my daughter back. I will try anything to keep her close. Wear her clothes. Sleep with her stuffed Puppy, and build a nest in my bed for her real dog, Suki. Marika loved sushi, so I take Rachel out for sushi dinners. Over and over, I play the few songs Marika had recorded. Yearning to know what it’s like to sing before a crowd, and how she could keep practicing a song “until it’s right,” I sing. One song. Musician/songwriter Susan Ceili Murphy put the first poem I found of Marika’s, “Atop a Mountain,” to music. I practice until I can get through it without bawling. Then I take it to France with me and sing it under vaulted ceilings in castles and cathedrals, wherever I find an echo. I sing it over hilltops, off the top of my hotel in Nice, in a boat on the Seine. I sing it to twelve goats in a barn in the Loire Valley, as the biggest goat cocks her head and squints skeptically at me. And back in Ithaca, walking Marika’s dog at night in the driveway, I sing the song to the stars. Finally, I sing it at the memorial in the middle of June.

No one in Ithaca, other than my babies, has ever heard me sing. Setting up for the memorial at the Stewart Park Pavilion on Cayuga Lake, I test the mic with the first lines of the song. There is a sudden hush and I realize I’ve grabbed people’s attention.

“You sound just like Marika,” someone says. Pleased about this, I step before the crowd shortly after, take a deep breath, and begin “Atop a Mountain.” It will take many more months to recognize that my singing would not be the way to hold onto my daughter. But at the memorial, I follow Marika’s voice through the song, without a crack until the last note. My heart pounds as I find my seat, and scoop my inherited dog up into my lap.

Her dog. People had wanted to see Suki. So I brought her, but I’m wondering if this was a mistake. She squirms uncharacteristically. Seeing and smelling so many of Marika’s friends, Suki’s searching frantically for her shining girl. Even though I had quickly become her new girl and she’d become my shadow, waiting for me in her nest by the front door whenever I’d leave the house. Having lost one of her girls, she does what she can to keep on top of the other. My song over, I bury my tears in Suki’s fur. She whines, and looks mournfully at the friends as Rachel begins “Changed for Good,” a song from the show, Wicked. Marika had once silenced a crowd at camp with that song. And now, out of Rachel’s mouth comes perfection. Even when she starts sobbing into the mic, and then apologizes. No one blinks when Rachel sings. And then Cassie sings. And Julie sings. Songs for Marika from those of us who rarely open our mouths in public. I imagine Marika watching us from above, dumbstruck.

“I don’t think I can do this.” I stood over my bin of plastic bags. “Earth Day’s coming, and I should be able to do this one simple thing for our planet,” I told myself. After decades of hoarding plastic shopping bags, I was considering eradicating them from my routine. But I kept coming back to all the things I do with these bags. Like carry gym-clothes and potluck dishes. Like use them for trashcan liners and dog-poo bags. They make great stuffing for stuffed-animal art projects. And long ago, inspired by Tom Knight’s song,

“I don’t think I can do this.” I stood over my bin of plastic bags. “Earth Day’s coming, and I should be able to do this one simple thing for our planet,” I told myself. After decades of hoarding plastic shopping bags, I was considering eradicating them from my routine. But I kept coming back to all the things I do with these bags. Like carry gym-clothes and potluck dishes. Like use them for trashcan liners and dog-poo bags. They make great stuffing for stuffed-animal art projects. And long ago, inspired by Tom Knight’s song,