“Why would you want to go THERE?” ask two stewardesses on my flight from Sydney to Melbourne, when I question them about transportation to Geelong, the gateway city for my next destination, the Great Ocean Road.

“To scatter my daughter’s ashes,” I gush out, in tears, overwhelmed by the first bit of interest anyone has shown in me since I got to Australia. I’m also a little terrified, having no plan for getting from the Melbourne airport to Geelong to the tiny town of Torquay where I have booked a room. This is not how I like to do things, not knowing what’s next.

From the airplane to the Melbourne shuttle, two train rides, two buses, and long walks dragging my rolling luggage behind, I am making my way, inch by inch, with direction-seeking and extended waits between each step. It takes all day to get from Sydney to the remote town of Torquay on Australia’s southeast coast. This second part of my journey is filled with questions no one back home could answer. Marika’s friend Carla would only tell me the Great Ocean Road must be discovered for oneself.

The first I’d ever heard of the Great Ocean Road was in April 2010 when, in the middle of her trip, Marika had phoned. Overjoyed to hear her voice, I was caught off guard. I thought she was homesick. I should have known better. She was calling to ask for extra money. To rent a car for a trip along the Great Ocean Road. It was “what everyone does on holiday from Melbourne.” I told her, No. So she and Carla took a bus.

Now here I am, two years after Marika’s trip, on a V-Line regional public bus, racing along a two-lane winding road that hugs a corner of Australia’s dramatic southeastern shoreline. The road ties together one hundred fifty miles of remote coastal towns and popular resorts. Prime surfing territory. I can’t take my eyes off the teasing blue sea which one minute seems ahead of me, just beyond a stretch of beach, then disappears and is suddenly smack below as we speed along atop high cliffs. We wind by rocky gorges, rolling foothills, secluded bays, and shipwreck coasts with towering limestone formations. Built as a memorial to the fallen soldiers of World War I by the returning soldiers, and later the jobless of the Great Depression, the Great Ocean Road is one of Australia’s National Heritage Sites. Tour buses from Melbourne regularly run its length, stopping at the most dramatic spots, the stunning seascapes in Marika’s photos.

Finally arriving in Torquay at the east end of the road, in a new motel room I reconstruct the altar of photos, chocolates, and stuffed Puppy, around the box of ashes. Then, wanting to locate the trailhead before dark for the next morning’s mission of ash-scattering on Bells Beach, I question the motel’s friendly bartender. No one else is around at that moment. So he closes up shop and leads me to his car. I hop in. He’s not really a stranger, I tell myself. But I sit poised for escape anyway. He drives a short distance down a deserted road.

“Yer sure ya want to walk all the way from the motel ‘n the morning?” he asks, regarding me like I’m crazy. “It’s a long way.” I don’t want to look at him. What am I doing in this bartender’s car anyway? He keeps driving.

“Nine kilometers, that’s only like six miles. Not much elevation change. Why not?” I say with a rising cloud of doubt. He shakes his head. I must look old to him, this kid running the whole show here. A hotel, motel, gaming room, bar and bistro, all in one, the Torquay Hotel Motel is the liveliest place in this little town. Everyone including this bar-boy seems to be Marika’s age, maybe younger. “I can walk back from here, thanks,” I say once we reach the trailhead. My sense of direction flustered, I ask him, “Which way back to the motel?” just to be sure.

Back at the bar and bistro later, I borrow a knife to open the sealed box of ashes, to let Marika breathe. And to make sure I won’t be stuck way out on the beach the next day, unable to open her box without tools. It is my first time meeting her ashes. With held breath and quivering hands, I pry gently at the box. It opens easily, like she’s pushing the lid from inside. She’s a trillion tiny shards, like cool white sand on a beach at sunset. In a plastic bag. In a bewildering way she’s still beautiful. I stare at her. At what’s left.

“The internet’s crashed,” says the Hotel Motel bartender when I seek him out once more, to get online. “I’m sorry. This never happens. I’ll refund some of your money.”

“No, that’s okay,” I say, thinking I may have killed the Internet connection myself. I’d tried to google “how to scatter ashes” and the little iPad went blank. Connection disappeared. It went the way of my family and friends all during the past year whenever I’d mentioned anything about Marika or ashes. Or death.

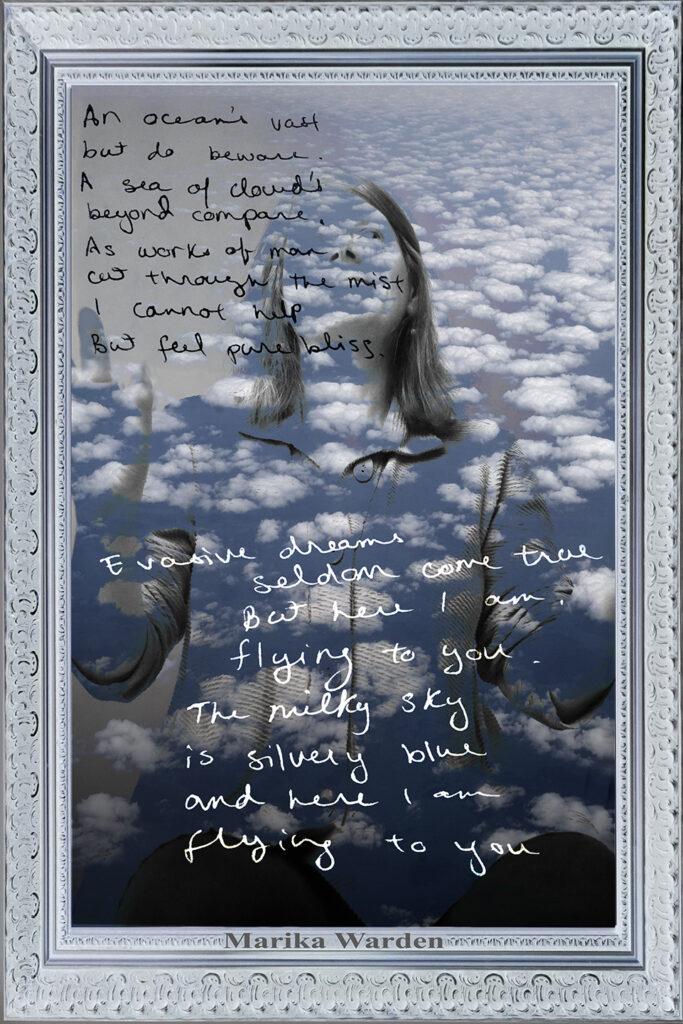

I didn’t have much faith I could learn efficient tossing techniques online anyway. I’d simply have to stand with my back to the wind and wing it. Tossing ashes. Flinging ashes. Ashes are typically “scattered” or “spread” if not kept forever in an urn on the mantle until someday some distant young relative has to figure out what to do with them. Marika had requested her remains be “scattered in Australia, if possible,” which gives me a lot of leeway. Spreading means smearing, like what one does with peanut butter or sunblock. So I’m glad she specified scattering. It gives me more a picture of sprinkling small amounts. Either way implies a distribution over a large area or several areas, broadcasting here and there, as opposed to just dumping it all in one place. And Australia is a vast continent, almost as big as the US. Early on I decided to leave ashes in the places I knew from her photos that she’d been happy.

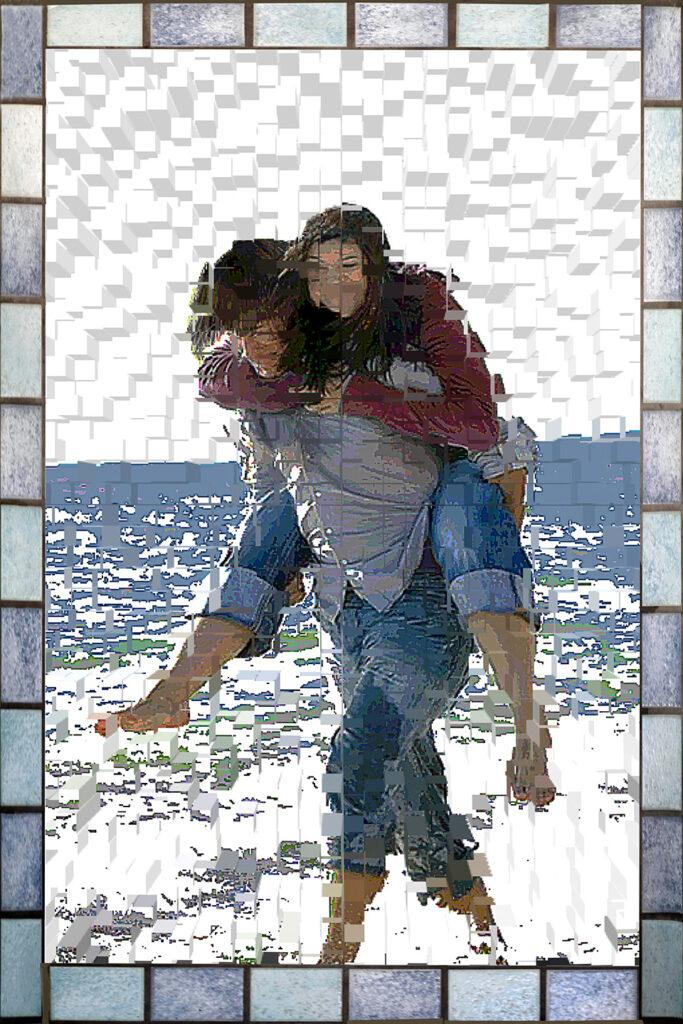

The next morning, I load Marika’s Ithaca Track and Field drawstring backpack with water bottles, a peanut butter and plum sandwich, and chocolate bars I’d hunted and gathered from the local grocery the evening before. I add maps, Marika’s stuffed Puppy curled into her baseball cap, and the ashes. But when I put the pack on, the box of ashes chafes at my back, giving me visions of Crusaders with heavy crosses gouging deep gashes across their backs and shoulders. I take the bag of ashes, maybe six pounds, out of the black box and gently stuff it back into the pack, leaving the box behind. With a full, heavy backpack I step out the door to a blinding sun. Quickly the bag of ashes settles into a rounded rump shape that bumps behind me as I walk a few hesitant test-steps around the parked cars. I imagine I’m carrying a life-sized Marika piggyback style. I can almost feel the swish of her heels swinging by my knees.

“Mom. Let’s go.” She kicks and nudges me in the direction of the trail. And so we’re off to Bells Beach. A long walk with a lot of weight, but all I need to do is keep on the right trail and be wary of the high tide at four-thirty the bartender had told me about.

“Oh, I’ll be done way before then,” I’d responded. Then he’d warned me to watch for the occasional big rogue wave, and I’d stifled a gulp.

Now, tall dark Norfolk pines line the beaches I pass. A long boardwalk over shallow water bounces under me as I tread the moist planks. When I reach solid ground, the landscape changes rapidly. Forest turns into scrub, and then into sandy coastline. Soon the path climbs. It becomes gravelly beneath sky that is dauntingly blue and forever. Under the hot sun, I lumber over rocks and cliffs, along crunchy red-sand footpaths, and through heathlands. Grasses, scattered trees, birds flickering in low woody bushes. Scrubland. The Surf Coast Walk twists and breaks off occasionally for lookouts. I whisper nervously to Marika’s ashes each time the trail splits. When it hangs over the shore, visions of falling from crumbling cliffs crash in my head. And I assure her—her ashes—we’re okay.

There are surfers out in the distance. A dog sits in the teeming shallows waiting for its owner. So much of surfing is waiting. You wait to be in the right place at the right time, wait for the right wave, and then fly with it. Hold on when you’re tossed, keep on top, re-find your footing when it’s lost, and then go the distance. As far as you can. And scramble back up again when you get dumped. And wait some more. It reminds me of living with cancer. Am I a cancer survivor, I wonder? Marika got wiped out by cancer, but I survived. Watching the surfers, I wonder how they don’t get completely mauled in the crashing waters.

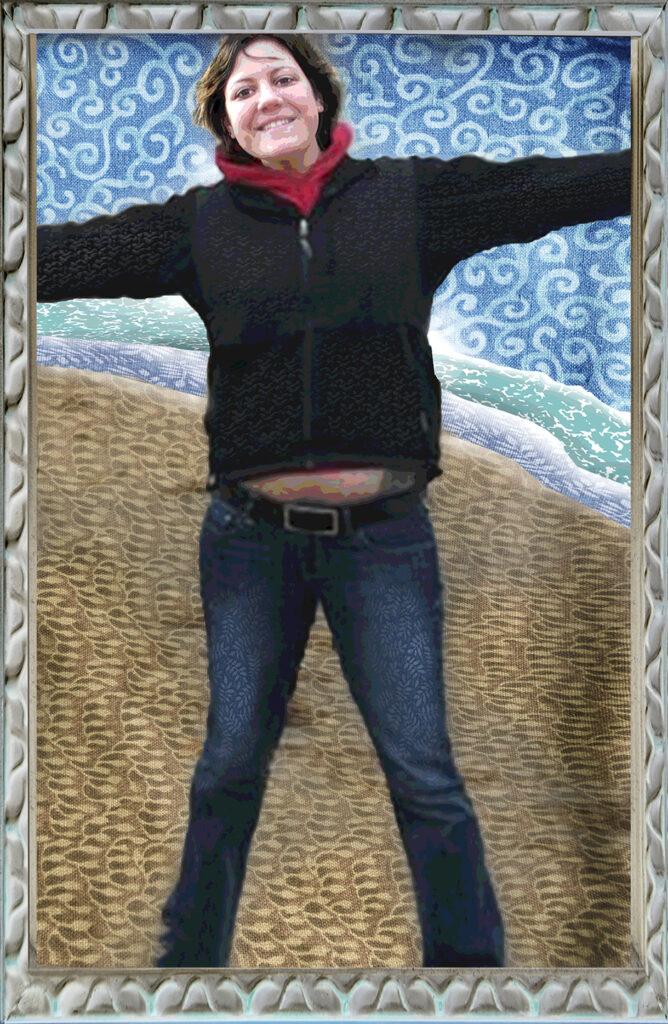

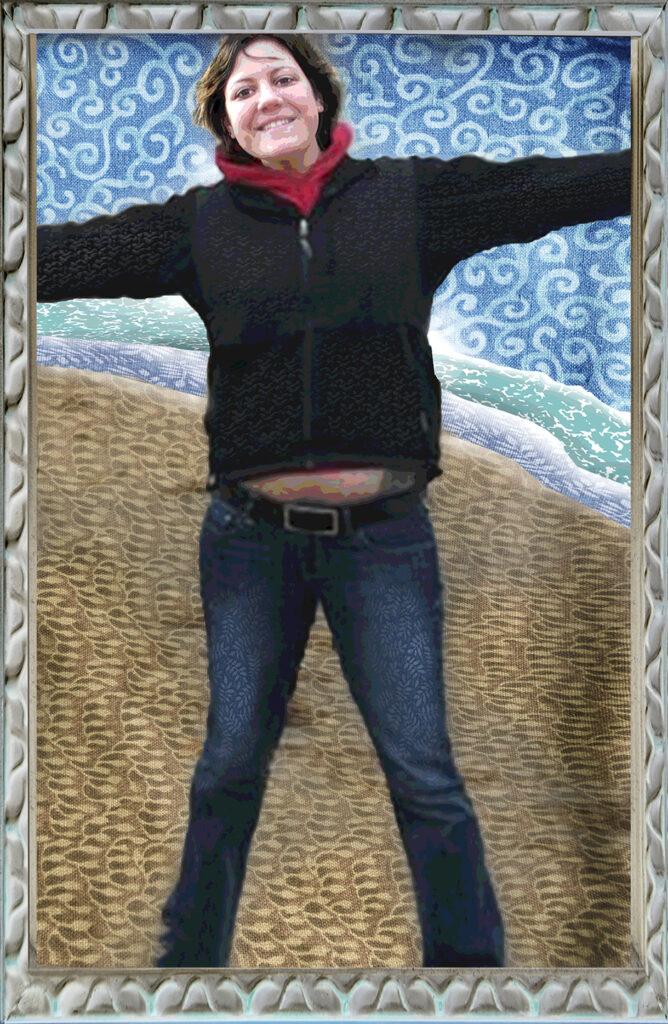

Three hours later, I climb down several sets of wooden stairs and stare at Bells Beach, the exact spot in the photo. The photo where Marika stands smiling, holding her arms out like she’s hugging the world. Only it’s an empty landscape before me now. It’s supposed to have her centered in front of the jutting point, arms lifted outward. Glued to the spot, sweating, I wait like I’m expecting to be met by her ghost.

An Asian tourist, bogged down with heavy cameras, passes by after a while and I give him my borrowed, pocket-sized point-and-shoot to take my picture in Marika’s place as I try to duplicate her pose. When the tourist is done and walks off, I am left alone on the beach. A kick at my back tells me Marika wants out of the bag, so I remove it from my pack, open its twist tie and inch closer to the water. Fears of waves and the incoming tide clash with the realization that I need to wade into the water to release the ashes. This is what I came all this way for, I tell myself. I can’t just spill Marika’s ashes onto the sand. So I kick off my sneakers, roll up my pant-legs, and cautiously slip into the seething surf. In knee-deep water the waves barrel into my body, soaking me almost to my waist. I brace myself against the poundings and try to ignore the stirrings in my head, “Don’t go out too far” and “Never swim alone.”