The Australia journey can’t end this way. It’s a year and a month since Marika died, and I’m walking in circles in Melbourne, hugging the last of her ashes on the last day of my trip.

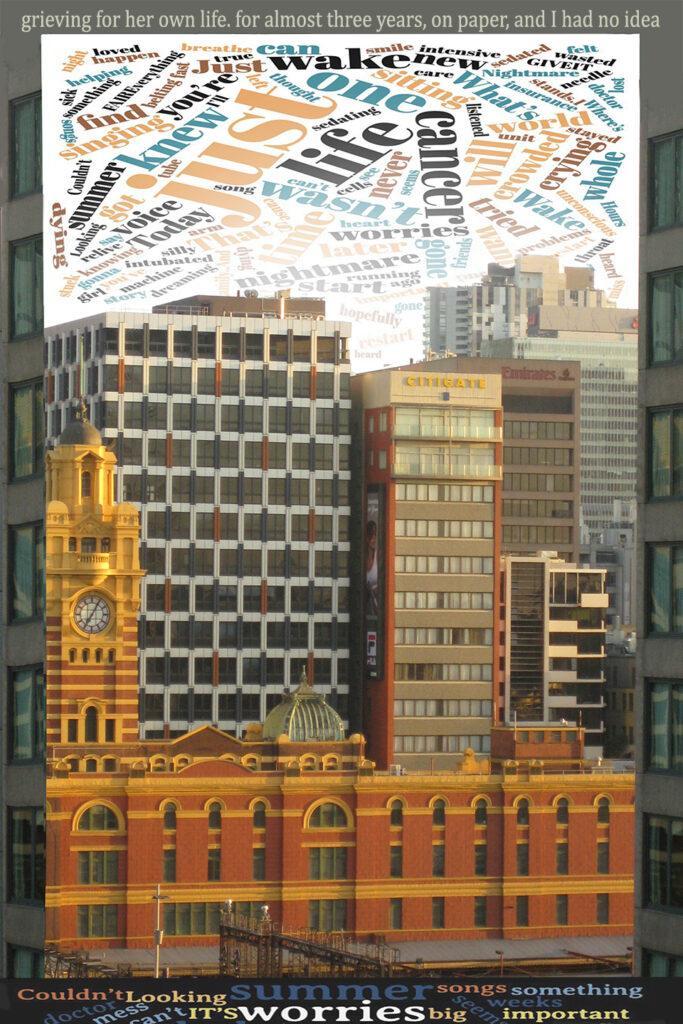

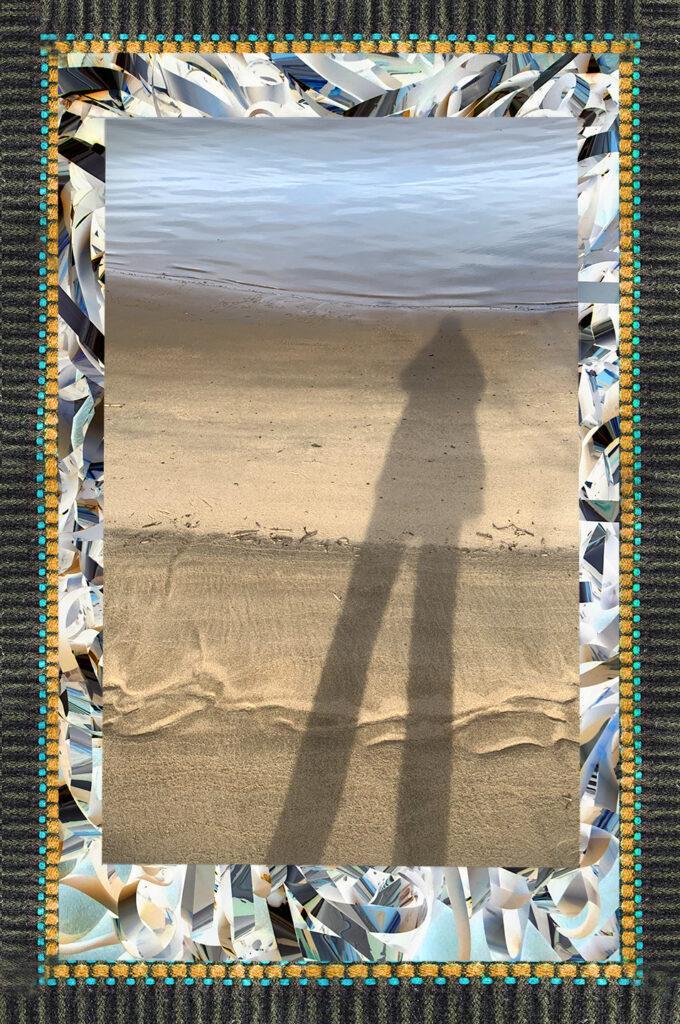

In a daze, I pass Federation Square in the center of Melbourne, the place where everyone meets up and hangs out. Soon I’m back on the Yarra River, behind Flinders Street Station from where one can start a journey to anywhere in the world. Everything leads to here and away from here. Whoever comes to Melbourne can’t miss it. People stroll along both sides of the river now. It’s midday. Musicians play, and street shows attract cheering crowds. The Yarra is lined with outdoor cafes, and filled with kayaks, paddleboats, cruise boats, and ferries. I sit on the edge of a small wharf and untie Marika’s bag of ashes for the last time. Ignoring everything, I begin to toss.

“This is for your Aunt Laurie, who wishes she could be here,” I whisper. “And here’s for Greg and your dad.” I toss another handful of ashes, “for Rachel, who loves you.” And another, “for your friend Jake.” I scoop and sprinkle a precious smattering of the ashes for Pat, Marika’s beloved Australian. And then I empty the rest of the bag.

“This is for me, Mareek. I love you…. I love you so much.” I turn the bag upside down and shake it clean. It makes flapping sounds like a bird taking off.

On the water’s surface, the ashes form a warm gray cloud like a pale ghost. It catches the sunlight and glimmers for seconds before disappearing into the river.

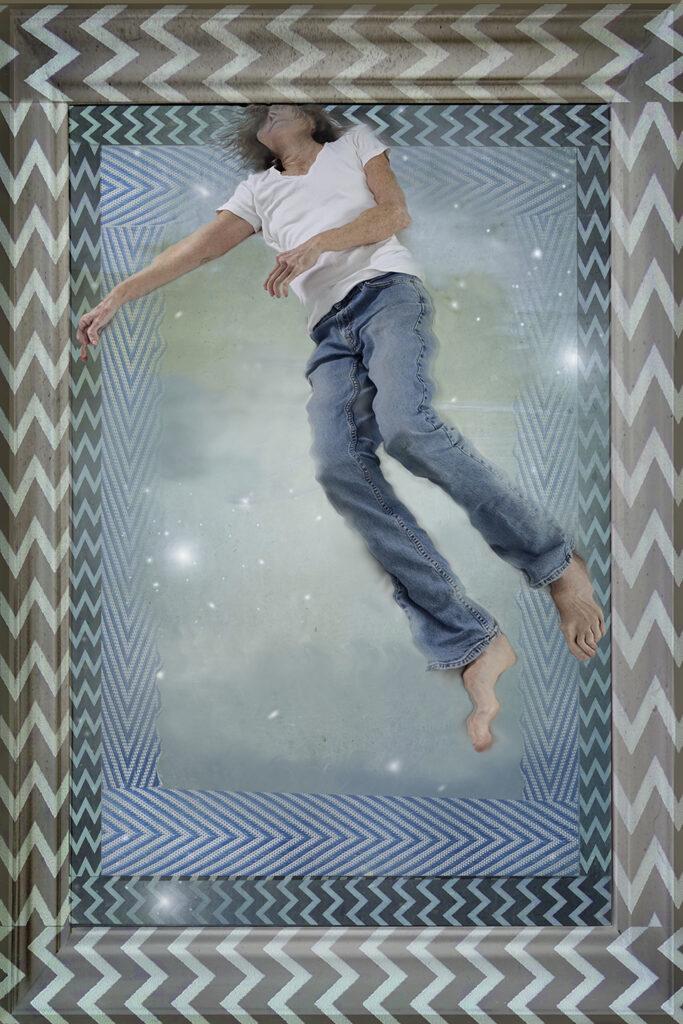

Marika Joy Warden from Ithaca, New York—you have been let loose in Australia, I announce in my head. She is free. Freed from the black box and plastic bags, doctors and drugs, rules and demands. Freed from cancer. And from the ashes, now blended into beautiful water.

I sit frozen. Seagulls whine. Small brown birds wait on the wharf. And from someplace deep inside my gut, faint tremors churn. I rock. Forward. Backward. Back and forth over the water, hugging myself. The rippled surface of the river reflects the sun and explodes in my face as I close my eyes on tears. Inside it is bright fiery red. Like flaming blood.

The birds do not leave until I tuck the empty bag away and stand. Don’t say goodbye; she’s not here, I think as I tear myself from the wharf. But she’s not completely gone either. Shortly after, she makes me dig through my pockets to give coins to nearby musicians. They thank me very enthusiastically, and I realize I’ve given them three whole Australian dollars instead of the seventy cents I meant to donate. And just as I reach the hotel, I hear a tiny hopeful voice, “Mom, what about the dumplings?”

I keep my promises. So later I head for the HuTong Dumpling Bar in Chinatown where they seat me before two dumpling makers who stretch and roll, pat, pinch, and pleat endlessly. I stuff my emptiness with Shanghai Dumplings and then return to the hotel, to the iPad, to check in with my friends.

Tomorrow’s coming. In the little hotel room, I hold Puppy and rock her like she’s a fragile newborn Marika. We’ll come back to Sydney with Laurie, I promise, we’ll do Puppy’s cremation on Manley Beach one day. I’m trying not to think about traveling back across oceans, vast seas of clouds, time zones, and mountains, and arriving home—alone—to an empty house. That night I sleep with Puppy under my arm.

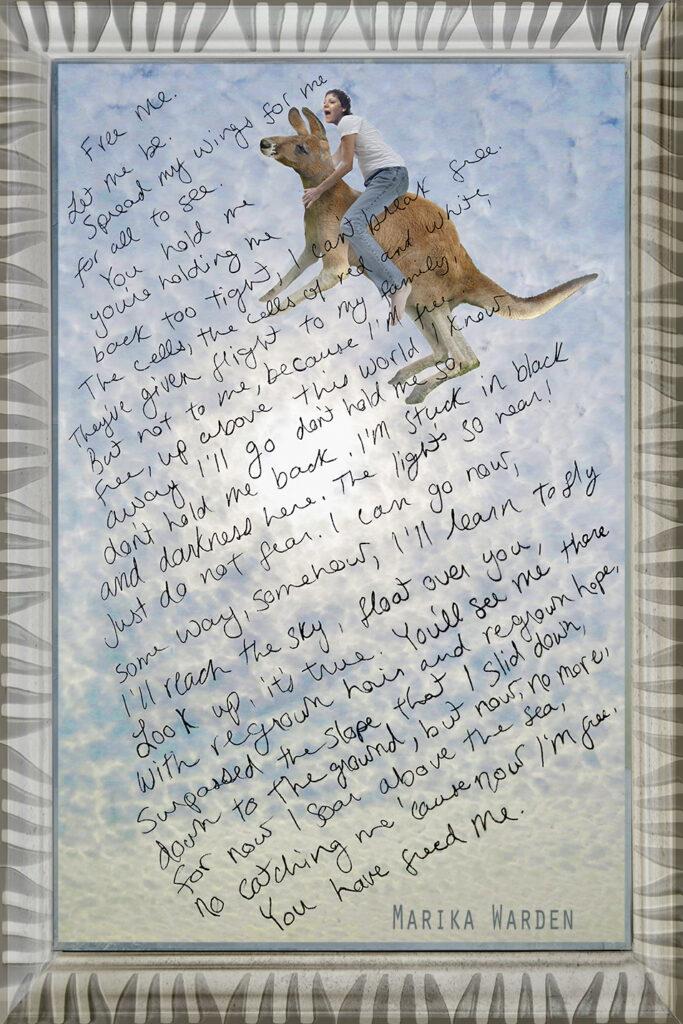

In the morning, on the plane as it taxies to the runway, I try to ignore the rubber band around my chest that tightens the farther I go from where I left Marika’s ashes. Then, as the plane takes off, I spot her, out the window in the distant grasslands. Marika riding her kangaroo. The kangaroo’s gait is oddly syncopated, and as it turns, I see they are each wearing an iPod earbud. Hey! I want to yell after her, I’m going to live bigger, live like the lights could go out at any time. Because anything’s possible.

The engines roar and the plane lifts off the ground. Peering down at my last glimpse of Australia, I raise my hand and rest it on the window. I’ll be back.

Don’t forget a single thing, I tell myself on the long flight: the road trips, Australia, the good things and the bad, all the scary parts. The waves. Her face. The white sheets wet with tears, Marika’s red-painted toes. How my back ached, sitting on the edge of the bed or standing over her to rub her feet. The glittering magic of just hearing her name. The heavy weight of not wanting to live when she died.

Through all of it, I believe the day after Marika’s death was the only time I wanted to die. That gray day in March 2011, I drove home to Ithaca from the hospital and then moldered a whole day, stuck in the hallway like a bled-dry carcass battered on a highway. Our journey together is over, I’d thought.

But that night I’d found her poems.

That marked the end of our journey together through the wilds of her cancer. The poems, delving into them and then duetting, kept me going until I birthed the plan for our journey to Australia to carry out her final wishes. The two journeys have ended now. The ashes are gone. And here I am, once more, returning home without Marika.

It almost feels like I’ve lost her again, lost her all over again. I’d spent the past year discovering the daughter I hardly knew, and then followed her ghost to Australia, all the while writing and rewriting, and rereading every bit of everything we shared. Marika died a thousand times over the year, for me. Yet something more of her always surfaced, some memory, some photo I hadn’t seen before, or some old friend telling me a Marika-story I hadn’t heard. That’s over now. The Australia trip is over. And now everyone expects me to move on.

Comfort is found in strange places. In our darkest times, we all have to find some one thing that we can hang on to. Maybe it’s a mission, an image, a dream. A song. Or just words. Something that brings us light and hope again. And peace. There’s this poem of Marika’s I keep coming back to.