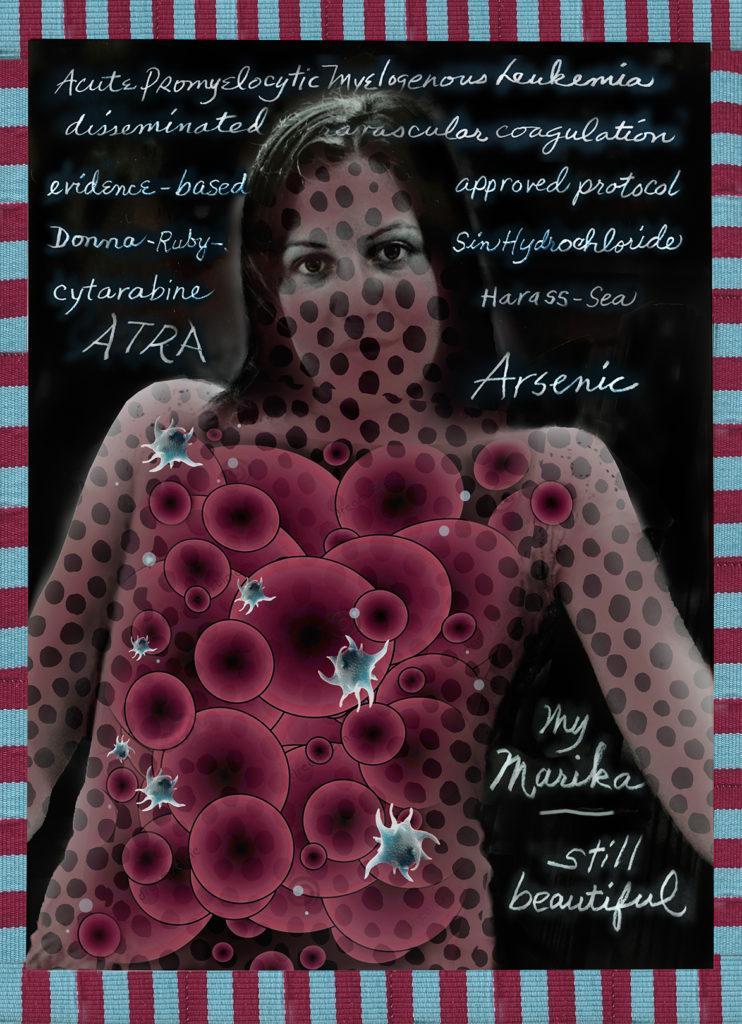

“When can we go home?” This was the one question I could always get away with in the hospital. It was our routine: ignore the nasty details, and push through to whatever we needed to hear in order to breathe. “She wants to know when she can go,” I’d say, but really, I, myself, hated being stuck in that creepy sunless hospital where I was turning languid and pale, sitting day after day immersed in my Ken Follett novel, World Without End. I was just as desperate as Marika was to be out of there. With luck, this second round of chemo would bring her blood counts back to normal and get her into remission. But Marika now had yellow skin and eyeballs. She was miserable with a head cold, fever, and stomach aches. Two weeks before, the Roc Docs discovered her inflamed gall bladder, but the surgeon couldn’t operate because she had no white blood cells to fight infection and too few platelets to stop the bleeding. Instead, they stuck a drainage tube in her side. It was now grinding against her tolerance.

“Mom, this sucks,” she yelled at me like it was my fault. We were constantly working to keep the tube and bile collection bag tied up in place with elastic bands and pins, tape, or anything that would hold until they could remove her gall bladder.

“Mom, where’s the tube?” she suddenly bellowed at me as if I’d taken it.

“What do you mean, where’s the tube?” We’d focused on little else the past week.

“The tube’s gone,” she said urgently.

“What did you do with it?”

“Maybe it fell out when I was in the vision clinic?”

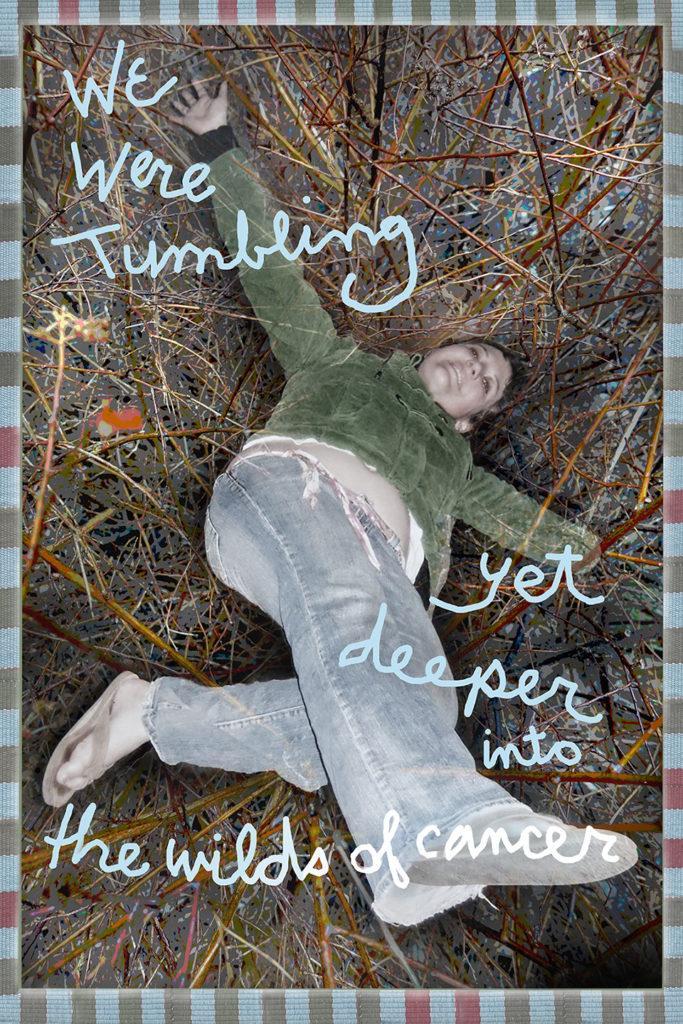

“You left the tube in the vision clinic?” I said in an exaggerated accusatory tone, trying to stifle a giggle. We both broke out laughing at the thought of some unsuspecting half-blind patient finding the bile tube sitting abandoned on a waiting room chair. We needed to laugh. Cancer had become a summer-long project and the path to remission was riddled with setbacks. It looked like it was far from over, and Marika was tired of being a cancer patient. I was just getting the hang of caregiving.

Being a caregiver is a lot like being a lifeguard. Except as a caregiver I had just one swimmer I didn’t dare take my eyes off of. And she’d already sunken a few times, so I told myself I knew what danger looked like. Still, the lifeguard in me rarely rested.

“Any minor cold you pick up, with your compromised immune system, could turn into pneumonia. A friend’s pinkeye or cough could end up in septic shock for you. A virus could lead to major organ malfunction. Any stray little fungus or bacteria could kill you. So, no sushi,” the Roc Docs reminded us. Marika wanted sushi takeout for dinner. She always wanted sushi.

“Oysters?” she tried again in a tiny voice.

“How about cooked sushi? You know, the ones with cooked shrimp,” I contributed, trying hard to keep peace and establish common ground. Doc Phillips conceded to that and my eyes checked in with Marika’s.

“Can I get a pass to leave the hospital for a few hours?” she pushed. She was always pushing. I went for the compromises while she straight-shot for the prize. “Can I start college next month?” It was the big question of the summer. It was what we all prayed for, but didn’t dare plan on or shop for, in fear of jinxing the whole possibility. There was still too much that could completely dash that dream. And we never knew where trouble would come from.

“There’s no more cytarabine. So we’re sending you home. We’re sorry,” the Roc Docs announced days later during morning rounds. “We tried to get some from other area hospitals but there’s a nationwide shortage.” My eyes met Marika’s for a brief second before turning back to the doctors in disbelief.

“But that’s my main chemo drug now,” Marika whimpered.

“We’re sorry.”

“Call your dad, I’ll call Laurie,” I said, not fully digesting the significance of the situation but aware this was news they would want to know about. A good lifeguard is always ready for the unexpected; one never knows when it’ll be necessary to leap in and pull somebody from disaster. I made the arrangements for a homecoming, and packed up efficiently as nurses removed Marika’s IV. Then, suddenly, two young residents charged into the room out of breath.

“They’ve located the drug in Buffalo at Roswell Park Cancer Institute. It’s being sent over now.”

By the time the IV team returned to go through the tedious process of locating another vein on Marika and replacing the IV, I was wilted over the foot of the bed.

“Mom. Mom!” She blasted her eyes at me and bucked her chin toward the technicians surveying her arm. I’d almost forgotten my opportunity to squeeze her hand.