Before leukemia, home was the place we came back to long enough to grab what we needed, whether it was a nap, a meal or a gym bag, as we rushed out again down the hill and back into the world. We rushed and everyone around us rushed. We rushed to get our homework done, to get to school on time, to go to soccer practice or to the mall to pick up some last-minute sports tape, and a fast smoothie to tide us over. As a new special education teacher, I pushed to get through paperwork that piled up too quickly, while Marika scurried between schoolwork and part-time jobs at her favorite sushi restaurant and the gym’s daycare center. There was never enough time. Maybe we liked to eat out so much because it forced us to sit still while we waited for our food.

We were foodies. She baked. I cooked when I didn’t have too much homework from my SUNY Cortland classes. I danced in the kitchen to the muffled sounds of Marika’s music. Indie rock. Upstairs in her room, where she thought no one could hear, she sang over pre-recorded instrumentals. And in the car, stuffed with singing girls, the joyful un-muffled voices made me smile as we sped off to soccer games in neighboring counties.

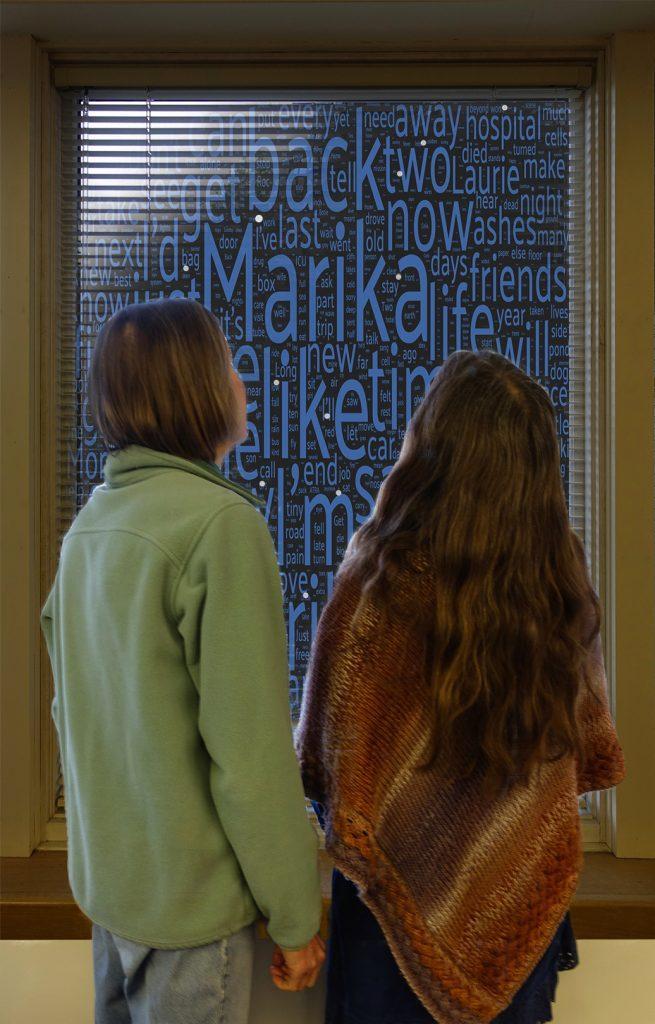

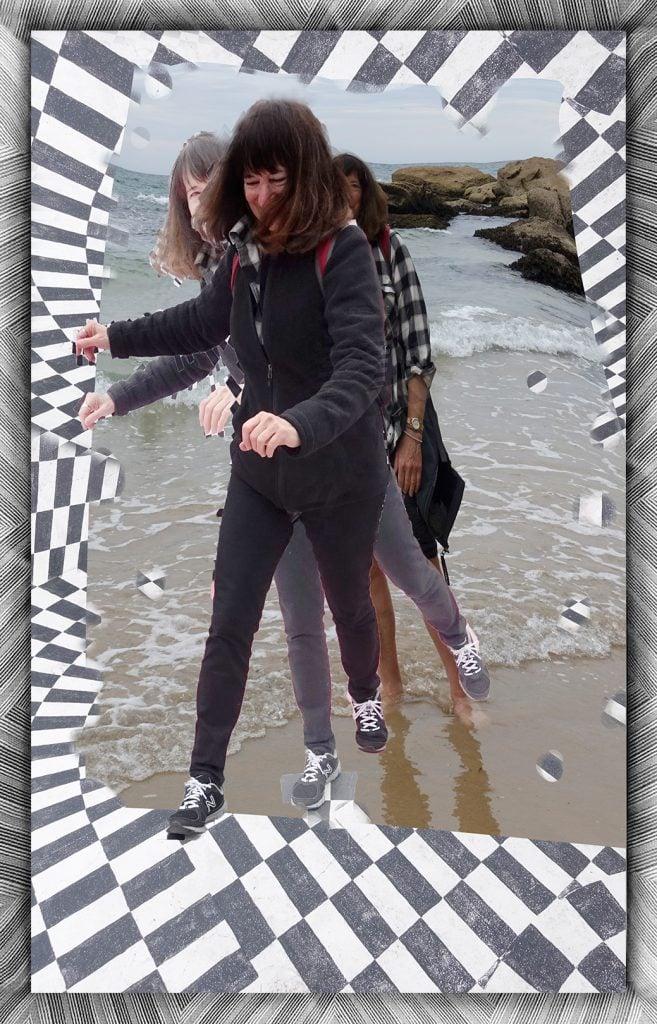

On the soccer field Marika was an aggressive tank, stopping at nothing to get at the ball. I winced whenever she headed it, and cringed every time she barged into another player. Marika was fierce; she was fearless. So of course she was going to fight leukemia. Early on, a friend set her up with a blogsite, Marika Kicks Leukemia. Though she lived in a dense fog the first few weeks of cancer, Marika was set for battle. She would fight her disease, her doctors, me, and anything else that kept her from living her life the way she saw it.

Life, the way I saw it, should be beautiful and function flawlessly. I always believed I could design my way into or out of anything. For me, to design is to control. It is ongoing, like breathing. Each day, before the sun rises, I envision every possible scenario so nothing can hit me by surprise. To put the most harrowing things in manageable perspective, I draw and make endless lists. There’s always a ‘Plan B’ as I bolster myself for the worst.

“I’m not worrying, I’m designing,” I insist, when accused of being anxious. And designing always started at home even though I hated being alone at home, and Marika would rather be anywhere else. But by the end of May 2008, home was where we both yearned to be.

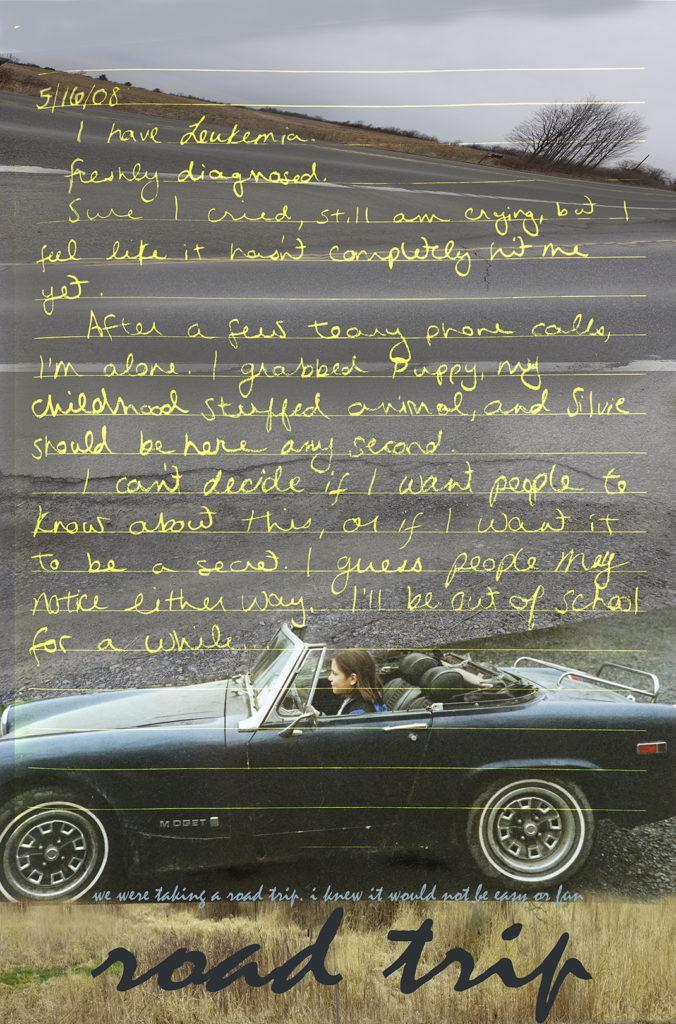

“When can I go home?” she asked countless times as teams of doctors filed in and out of her hospital room. First this had to happen and then that—there were obstacles. It was like Monopoly, one of those endless board games we always gave up on before we could finish. We were only at the beginning of our road trip. And my mind was already racing, working overtime to find “beautiful” and “flawless,” to put them back into our lives wherever we might land. But leukemia had wormed its way into the warp and woof of our world. Cancer hit home. The tides were broken. They’d collided. Soon I, too, could not “ride along to the same rhythm anymore,” as Marika said. We were hanging over the dark craggy cliff of the gorge when Marika nearly died two times in her first three weeks of cancer.

There was no way to design my way out of that.