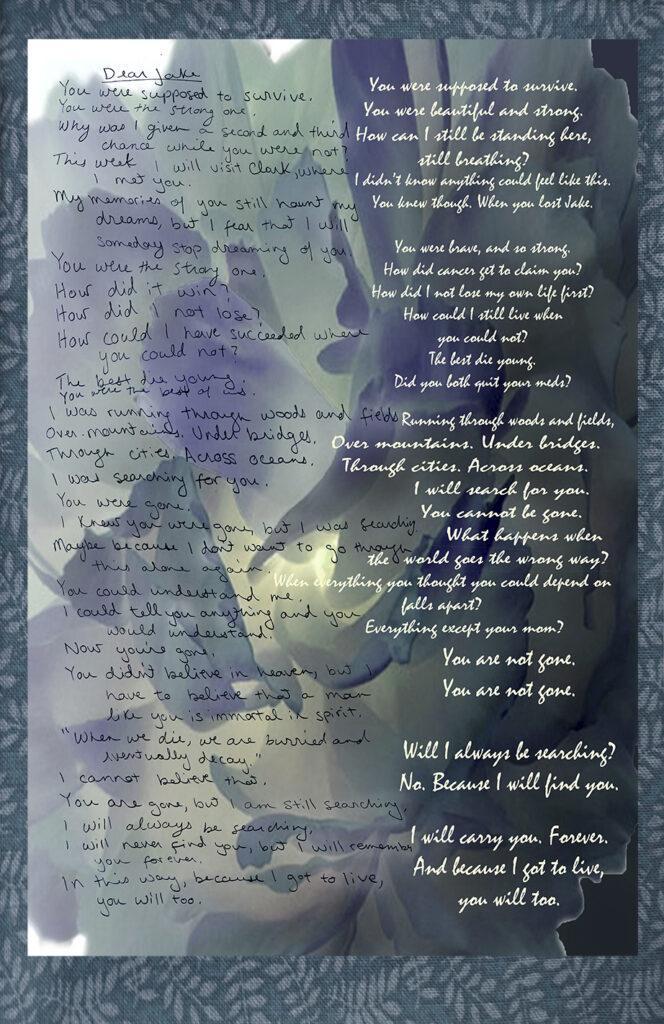

Nothing was simple or straightforward ever again after cancer hit home.

“Let’s toast to summer,” said my friends, as we clinked glasses at our first outdoor dinner of 2010. I pictured berry picking, pond swims, barbecues, and all the feasts we would cook up the next three months. In between Marika’s weekly blood draws and my search for a new teaching job, I would allow myself some time off. Marika had secured her job as boating counselor and lifeguard at the Stewart Park Day Camp. She had her apartment and her car. We both had new bathing suits. Finally, after missing the last two summers, our Best Summer Ever was about to begin. But in our lives nothing could be presumed anymore. There was no straightforward movement towards any end. I should have known better than to celebrate.

Marika’s friend Rachel, hanging out at Limbo before leaving for summer school at Long Island’s Hofstra University, was also anticipating summer. “I just have Anatomy-Physiology to finish up and then I’m done,” she told Marika, chewing a mouthful of Australian cookies.

“Did you just eat the whole box of TimTams?” Marika chided her. With chocolate crumbs dotting her face, Rachel shook her head, licked her lips and grinned, “You should visit me on Long Island this summer.” But Marika was preoccupied inspecting the countless unaccounted-for bruises on her arms and legs. She knew what that meant.

“What is it about cancer and summer?” I asked Laurie, that night, over the landline. “It’s exactly a year after her first relapse, and that was a year after her first diagnosis. Why always summertime?” We quickly resumed our old routine where I relayed to Laurie the medical terms doctors threw at us, so she could breathe meaning into them.

“It’s the same type of leukemia,” she said.

“Laur, they told us they ran out of drugs to treat her with,” I wailed.

“Well, there’s one mega-problem with the second relapse: there are no standard forms of treatment.” I squeezed the phone as Laurie continued. “The only option is to find an experimental drug in Phase Two of its clinical trial, meaning they are ready to try the drug on significant numbers of people—I guess the mice must have lived.”

“So what’s the good news, Laur?” I asked hoping to eliminate the scenes of squirming cancerous lab mice stuck in my mind.

“She might get to keep her hair?” Laurie said, questioning herself. “You get to travel,” she added, more sure of this possibility. The Roc Docs had been consulting with colleagues in Chicago about a drug being used in Japan. They wanted to send us to Chicago, but Laurie went online and discovered clinical trials for the same drug being conducted on Long Island. In order to get a new drug, we would have to show up regularly at a cancer center. We couldn’t simply have a new box of pills mailed to us and just continue with our lives. So we were on the phone making plans to go to North Shore Medical Center in Manhasset, one town over from where I grew up.

“I hate Long Island!” Marika stated. Emphatically. I shushed her, and hunched over the phone.

“Can you come down the day after tomorrow?” Pat Li, our contact nurse at North Shore, asked. The quick responses from the clinical trial people surprised me. Did they sense our desperation to do something—anything—to be rid of cancer? Or did they need us, need more human guinea pigs? We packed half-heartedly as Marika had not yet been accepted into the program. We wouldn’t find out if she qualified until our first appointment. If she did, we would remain on Long Island for three weeks. If not, we would turn around and go home. There were too many questions either way. Like where would we stay if she qualified? And what would we do if she did not? Whether or not her father’s health insurance would cover it, I didn’t dare consider yet.

“Wifey, it’s only seven minutes from my school,” Rachel said joyfully to Marika, “You’re definitely visiting. We’ll have a blast.” Oblivious to Marika’s sentiments about Long Island, Rachel was already making plans.

“I’m not going,” Marika said on the morning of the first appointment for the clinical trials. She had slept at the house to make for an easier early morning departure. It was time to go, and I was anxious about dealing with New York City rush hour traffic, finding the medical center, and maybe being told she didn’t qualify for the trial. “I’m not going,” she said again, banging the refrigerator shut. We had at least a five-hour drive ahead of us and she was already being difficult.

“Mareek, this is our best bet to get you into remission. Our only bet.” I was sweating, and my head was beginning to hurt. “What on earth is the problem?” I was losing it. My voice got higher. Louder. “I’ll meet you in the car in ten minutes,” I said, praying things would not explode into an outright war, or worse, in her disappearing on me. I’d made breakfast and delivered the tray to her room. I’d walked her dog and driven it to family friends who would take care of it. I made Marika’s special tea with lemon and honey in a thermos for the road. So she was supposed to cooperate now.

“I. Don’t. Want. To go.”

“Okay, what do you need to have happen so that we can get moving? Because I’m getting nervous. This is not my idea of fun. Who wants to be driving to Long Island? Of all places! I thought I was done with Long Island years ago.” I was ranting uncontrollably, “And they might just send us home with nothing. And then what? You would miss our last chance for a cure because you don’t like Long Island?”

“I don’t want to talk,” she said, her tone matching mine. “I’ll go, but don’t talk to me. If I hear your voice I’ll jump out of the car.”

I opened my mouth, then caught myself and nodded instead. But she had already thrown herself into the back of the car with earphones plugging her ears, her thermos of Get Gorgeous Tea and a thick invisible wall between us. We drove in silence and got caught in morning rush hour traffic, as I knew we would.

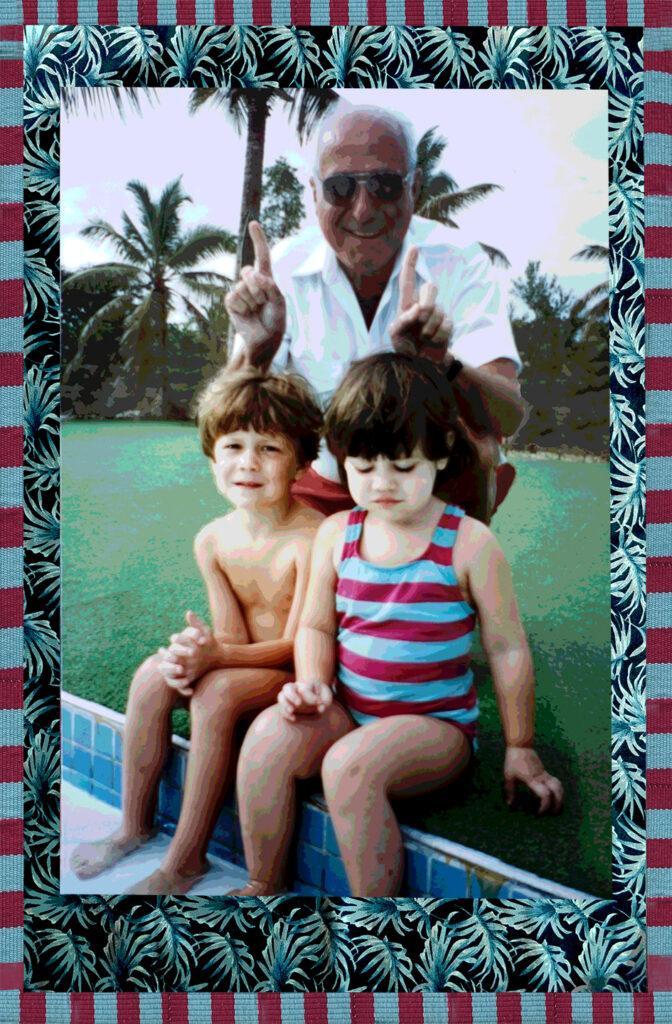

As far back as my mind can remember there was anger every place I called home. I was attracted to it and it followed me everywhere: my childhood ranch house on Long Island, the palace on Ithaca’s West Hill, the homes by the ponds. Anger lurked in the walls and ceilings, in the carpets and closets, in every corner. It seethed in the spaces between the inhabitants. It was inherited; it was contagious. It could boil for months, sometimes seeping through the cracks before erupting completely, violently. My own small blaze was mostly suffocated in passive-aggressive smoldering. I got away with that for most of my life. And when I should have been most angry, my little fire turned to ashes. It disappeared somewhere in the sad miles and years of shuffling my young children back and forth between two simmering households. I watched the anger grow in my kids. My son eventually found it useful for survival in combat. In Marika, it came out in fierce tantrums. By the time cancer crept into our lives, my own anger had mostly dissipated in the raging storms around me. Seeing it in the eyes of the ones I loved, chilled my heart.

“Let me know if you want me to stop at this rest area,” I said, breaking four hours of silence. “I think it’s our last opportunity.”

“Don’t talk to me!” She kicked the back of my seat. For the first time I wondered, if we were to go home that day, if she might possibly be able to ride back with her father and his wife. They were already in the waiting hall of the medical building on Long Island.

Finally, we were stuffed into a small office at the medical center. More chairs were crammed in to accommodate Marika’s father and his wife. And Rachel. We had not planned on including Rachel in this meeting but everyone was grateful to have her there. With her EMT training, she was savvy about medical proceedings, and the one thing we could count on was Rachel’s ability to calm Marika. Besides, somehow she always showed up, whether or not she was invited.

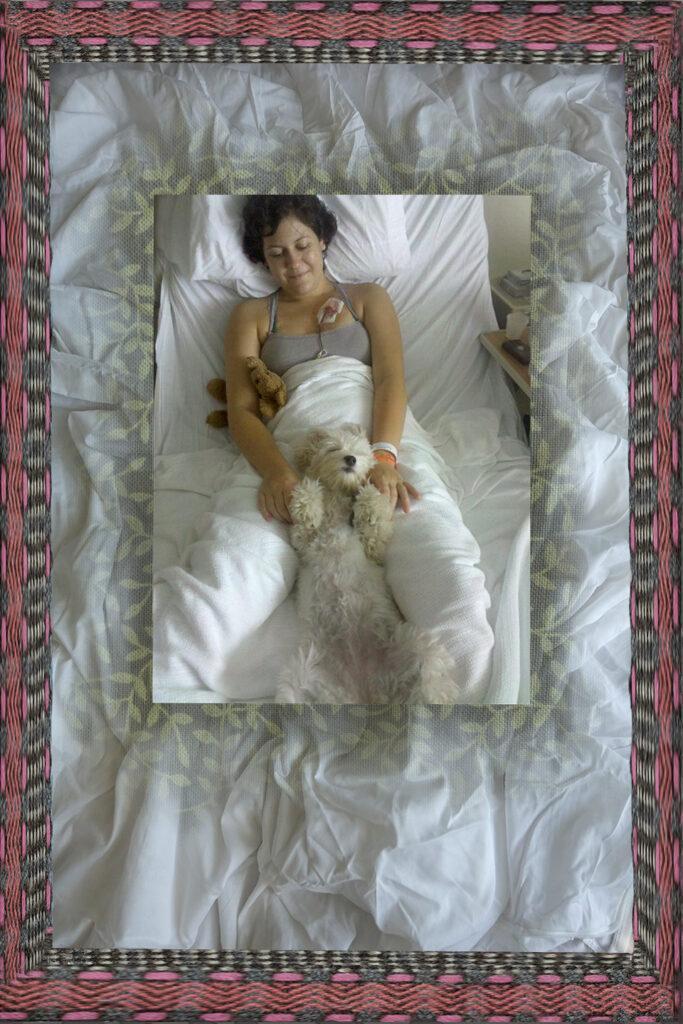

Pat Li and the new doctor introduced tamibarotene, our new drug. The TammyBear-o-Teen pills were parceled out like expensive French truffles. They were to be taken mindfully, at particular times twice a day. Each dose was to be checked off and recorded in three places on various forms. The drug was ten times more potent than the ATRA Marika had taken the first two summers, the ATRA that had given her seizures and landed her in the ICU with respiratory failure. The good news was there would be fewer and less severe side effects with TammyBear-o-Teen. And Marika would not lose her hair.

“It is not a cure,” they reminded us. “A transplant is the only cure, and for that she must be in remission. This drug will get her into remission, and then she can have a stem cell transplant. As soon as possible.” I finally understood the whole plan. We could all see where we were headed. It seemed straightforward. Simple.

Please Share on your Social Media