Tag Archives: bereaved mother

Duetting: Memoir 61

Barely twelve hours after landing in Ithaca, on my return from Australia, I fall head first and hard into my front door. And break my nose. Slowly, I lift myself up from the load I’d tried to carry into the house. Two huge garbage bags of cat-poop and soiled litter my cat-sitting friends had collected and sent back with the cat. The cat is still in the car, crying in his carrier. But I’m holding onto my head, barely able to breathe. A million things could have gone wrong in Australia, but they didn’t, and here I am, back on my own doorstep, losing my balance, falling apart.

My nose rains blood. Stars flash before my eyes. My fingers fumble blindly over the newly reactivated cell phone in an effort to reach someone for help. In the emergency room, I hold my face for hours as my memories of Australia evaporate. I beg the doctor for a new nose, a nose job. Impossible, he says, but he can fix the break. I wake up after the surgery wishing I could sleep through the healing. But even sleeping is difficult, done sitting up in a zero-gravity lawn chair parked next to the bed where cat and dog keep vigil over me and the tray of tissues, pills, and tippy-cup with water.

Over the next weeks my face turns the color of stormy oceans, then of green-gray grass, and finally a yellowish shade like wheat ready for harvest. I write feverishly as I nurse my nose. I watch the crazy geese on the pond. They hoot and honk. They do their nesting and protective dances all over again. From the south windows I follow the geese and the slow changing of the moon.

“Hey, Marika in-the-moon,” I call to her when it’s a full moon. When it’s a fingernail moon. On moonless nights when I walk her dog. “Do you see the moon, Suki?” I talk to the dog. I talk to Marika. I talk and sing to Marika’s moonbeam smile in her life-size photograph that hangs prominently in the middle of the house. It all helps.

Late spring nights I try to sleep, breathing through my mouth, as around the pond the songs of a thousand frogs echo in high peeps and low gunk-gunks. Frogs gulp and grunt. They scream into the dark night. Windows open or closed, it doesn’t matter though. Mostly I hear only the muddled noise of my mind trying to make sense of life’s events. I wait in the tumult of the night until the din dies down, or doesn’t.

The days are filled with friends who check on me, prying me from my writing. They listen. It helps to have friends, especially those who also have lost loved ones.

My friend Andrea dies. My children’s mentor. The one who believed in me. Cancer.

I lie on my back on the living room floor. Suki, my inherited dog, stands over me, engrossed by this new perspective. She pokes her inquisitive little nose into my still-sore face, and I can’t help but smile. Then she drops a squeak-toy on my chest and I explode into laughter. The sound of my own high-pitched squeals fascinates me. But it soon dissolves into a howling cry as I sink back into sorrow. Marika. Now Andrea. Has cancer always destroyed so many lives and I just never noticed? Suki stares at me, terrified. When I quiet down she licks the tears around my healing nose.

By the end of June my blog site is up. If I want to be a writer, I’m told, I need to have a website and write a weekly blog. And find followers on Facebook and Twitter. Oh, if Marika could see this. More and more, it seems, I’m living my daughter’s life. Only I’m shy and clueless as to social media. Communicating with strangers makes my neck muscles tense up and renders me almost wordless. But it is the only commitment I have, so I treat it like it’s my job; every Monday morning, no matter where I am or how I am, I publish an article. I reach out to family and friends, to Marika’s friends, and to people I have not yet met. I’m never sure of what to say. So I write the stories of my stumbling into deep holes of grief, and my attempts to crawl back out. In the hope it will help someone. We’ve all lost someone or something we loved. There’s life after loss. That’s all I’m trying to say. Or, it’s what I’m trying to believe.

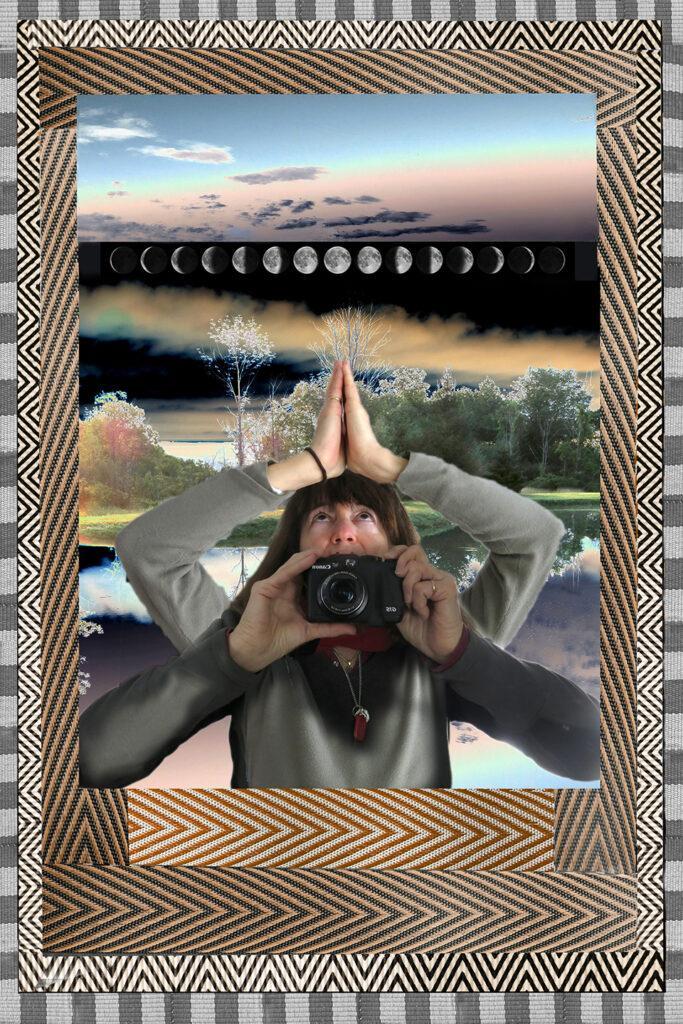

Way before our colliding with cancer I had developed an aversion to producing visual art. So I’m not sure what on earth led me to enroll in a Digital Photography course at Tompkins Cortland Community College in the fall after the Australia trip. I know nothing about photography. I’d borrowed a small point-and-shoot for Australia and could barely manage that. Computers and technology in general confound me. And here I am in a class with tech-savvy college students and a handful of retired folks with huge expensive cameras hanging around their necks like gigantic gaudy jewelry. The only thing I have going for me is my sense of design. And maybe my newly developed adventurous spirit born from the discovery that I need to actually do something in order to have something to write about in my blogs. But there’s this keen desire to breathe visible life into my memories of Marika. Like one huffs and puffs at the last embers of a dying campfire.

So I rent a digital camera from the school and photograph whatever sits still long enough for me to consider f-stops, shutter speeds, and ISO settings. Right off, I learn to photo-shop pale images of Marika’s face onto all my landscapes. Soon I’m ‘shopping away, trying to make impossible scenes appear somewhat real. I ‘shop Suki a dozen times all over the living room, in one picture. I enlarge Marika’s face until I can gaze into her life-sized eyes. Working in Photoshop is the closest I’ve come to finding peace. Or God, maybe. Time and troubles disappear when I ‘shop. The making of each picture is a prayer of gratitude. It’s comforting to me, if not actually useful. It’s challenging. I stagger out of class each week dizzy with new ideas. And in my weekly blogs I add photos to complement what I write.

It doesn’t take long to notice that my approaches to writing and photography differ. I work hard to find the exact words to describe reality. How something feels, smells, sounds, and tastes. I could never write fiction. But when I photo-shop, I can tell a more colorful story. So I tell the truth in words, but shamelessly stretch it in my photos. And I call the whole thing ‘healing.’

Duetting: Memoir 60

The Australia journey can’t end this way. It’s a year and a month since Marika died, and I’m walking in circles in Melbourne, hugging the last of her ashes on the last day of my trip.

In a daze, I pass Federation Square in the center of Melbourne, the place where everyone meets up and hangs out. Soon I’m back on the Yarra River, behind Flinders Street Station from where one can start a journey to anywhere in the world. Everything leads to here and away from here. Whoever comes to Melbourne can’t miss it. People stroll along both sides of the river now. It’s midday. Musicians play, and street shows attract cheering crowds. The Yarra is lined with outdoor cafes, and filled with kayaks, paddleboats, cruise boats, and ferries. I sit on the edge of a small wharf and untie Marika’s bag of ashes for the last time. Ignoring everything, I begin to toss.

“This is for your Aunt Laurie, who wishes she could be here,” I whisper. “And here’s for Greg and your dad.” I toss another handful of ashes, “for Rachel, who loves you.” And another, “for your friend Jake.” I scoop and sprinkle a precious smattering of the ashes for Pat, Marika’s beloved Australian. And then I empty the rest of the bag.

“This is for me, Mareek. I love you…. I love you so much.” I turn the bag upside down and shake it clean. It makes flapping sounds like a bird taking off.

On the water’s surface, the ashes form a warm gray cloud like a pale ghost. It catches the sunlight and glimmers for seconds before disappearing into the river.

Marika Joy Warden from Ithaca, New York—you have been let loose in Australia, I announce in my head. She is free. Freed from the black box and plastic bags, doctors and drugs, rules and demands. Freed from cancer. And from the ashes, now blended into beautiful water.

I sit frozen. Seagulls whine. Small brown birds wait on the wharf. And from someplace deep inside my gut, faint tremors churn. I rock. Forward. Backward. Back and forth over the water, hugging myself. The rippled surface of the river reflects the sun and explodes in my face as I close my eyes on tears. Inside it is bright fiery red. Like flaming blood.

The birds do not leave until I tuck the empty bag away and stand. Don’t say goodbye; she’s not here, I think as I tear myself from the wharf. But she’s not completely gone either. Shortly after, she makes me dig through my pockets to give coins to nearby musicians. They thank me very enthusiastically, and I realize I’ve given them three whole Australian dollars instead of the seventy cents I meant to donate. And just as I reach the hotel, I hear a tiny hopeful voice, “Mom, what about the dumplings?”

I keep my promises. So later I head for the HuTong Dumpling Bar in Chinatown where they seat me before two dumpling makers who stretch and roll, pat, pinch, and pleat endlessly. I stuff my emptiness with Shanghai Dumplings and then return to the hotel, to the iPad, to check in with my friends.

Tomorrow’s coming. In the little hotel room, I hold Puppy and rock her like she’s a fragile newborn Marika. We’ll come back to Sydney with Laurie, I promise, we’ll do Puppy’s cremation on Manley Beach one day. I’m trying not to think about traveling back across oceans, vast seas of clouds, time zones, and mountains, and arriving home—alone—to an empty house. That night I sleep with Puppy under my arm.

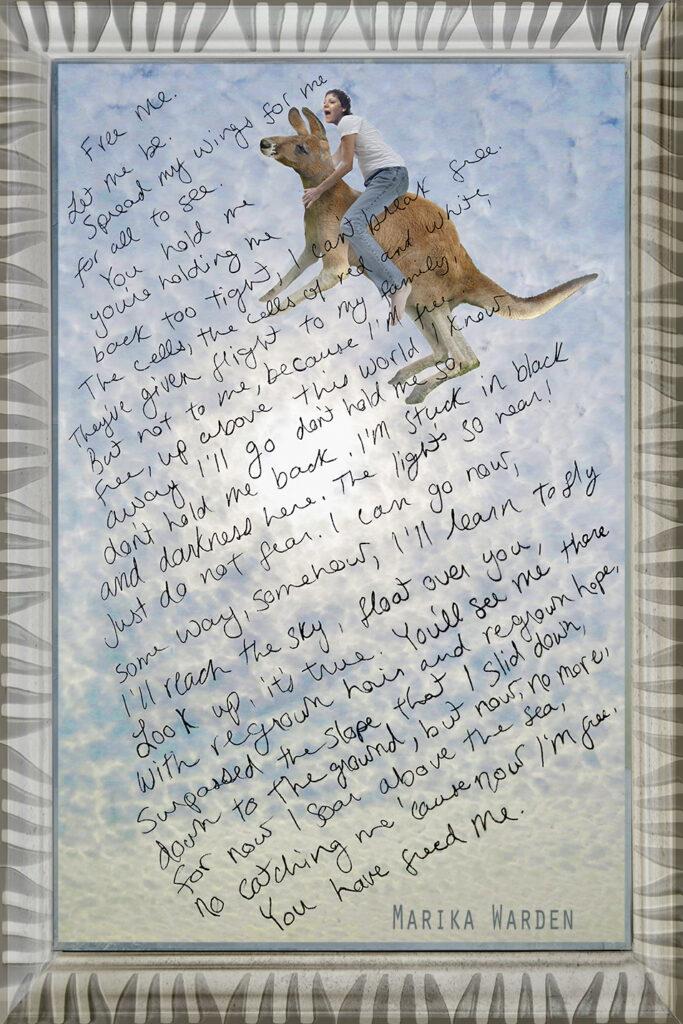

In the morning, on the plane as it taxies to the runway, I try to ignore the rubber band around my chest that tightens the farther I go from where I left Marika’s ashes. Then, as the plane takes off, I spot her, out the window in the distant grasslands. Marika riding her kangaroo. The kangaroo’s gait is oddly syncopated, and as it turns, I see they are each wearing an iPod earbud. Hey! I want to yell after her, I’m going to live bigger, live like the lights could go out at any time. Because anything’s possible.

The engines roar and the plane lifts off the ground. Peering down at my last glimpse of Australia, I raise my hand and rest it on the window. I’ll be back.

Don’t forget a single thing, I tell myself on the long flight: the road trips, Australia, the good things and the bad, all the scary parts. The waves. Her face. The white sheets wet with tears, Marika’s red-painted toes. How my back ached, sitting on the edge of the bed or standing over her to rub her feet. The glittering magic of just hearing her name. The heavy weight of not wanting to live when she died.

Through all of it, I believe the day after Marika’s death was the only time I wanted to die. That gray day in March 2011, I drove home to Ithaca from the hospital and then moldered a whole day, stuck in the hallway like a bled-dry carcass battered on a highway. Our journey together is over, I’d thought.

But that night I’d found her poems.

That marked the end of our journey together through the wilds of her cancer. The poems, delving into them and then duetting, kept me going until I birthed the plan for our journey to Australia to carry out her final wishes. The two journeys have ended now. The ashes are gone. And here I am, once more, returning home without Marika.

It almost feels like I’ve lost her again, lost her all over again. I’d spent the past year discovering the daughter I hardly knew, and then followed her ghost to Australia, all the while writing and rewriting, and rereading every bit of everything we shared. Marika died a thousand times over the year, for me. Yet something more of her always surfaced, some memory, some photo I hadn’t seen before, or some old friend telling me a Marika-story I hadn’t heard. That’s over now. The Australia trip is over. And now everyone expects me to move on.

Comfort is found in strange places. In our darkest times, we all have to find some one thing that we can hang on to. Maybe it’s a mission, an image, a dream. A song. Or just words. Something that brings us light and hope again. And peace. There’s this poem of Marika’s I keep coming back to.

Duetting: Memoir 59

It was not like tucking her in. After my daughter’s last breaths and the moments the hospital staff reserved for the family’s final goodbyes, it was more like stripping down the Christmas tree. Off with the earrings. Then the navel ring, and the woven friendship band on her ankle. Off with the bracelet her brother brought back from Iraq. And stuffed Puppy, always held in the crook of her arm. Off. They said it all had to come off. I was left holding precious bits and pieces of my beautiful daughter, trying hard not to think about what would happen to her next.

Mom! Get over it! I heard Marika’s voice in my head. So I gave it all to her father. Except for Puppy. Almost threadbare Puppy was still warm from her. For a long quiet time I held Puppy, and stared at Marika’s empty house, getting used to the idea that she wasn’t there. And then I left, so they could take her beautiful house away.

They kept me busy. I don’t know who was with me, my friend Celia, my son? My sister? Didn’t matter, because Marika was not. I allowed myself to be led around. There was a walk to some local coffee shop to buy lots of gift cards that would be left in the Oncology Unit. There was packing up. Her things. My things. There was dinner in a restaurant where all I can remember is wondering how I could eat. And how Marika could not eat. How she, her body, her house, was stuck in the hospital, in the cold basement morgue while we were dining out. Her perfectly shaped eyebrows and red-painted toenails and all the rest of her that I’d never get to see again was now stuffed into some black plastic body-bag with not even a blanket to keep her cozy and warm. She had lain so still and vulnerable in the center of us. Helpless. And now she was alone in the cold dark, awaiting cremation.

I need to forget this last part. That is not how I want to remember her.

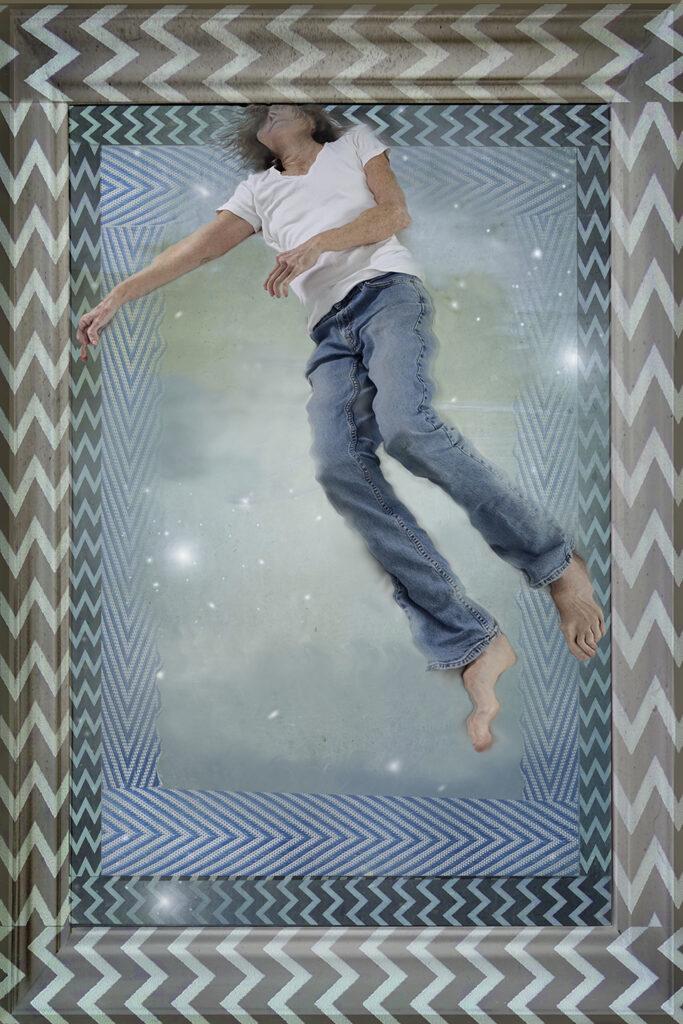

It was late. I returned to Hope Lodge without my hope. One last night in Rochester, that would forever be the city where I left Marika. Where I knew I’d have to return some day but knew I would never want to return. And that night, in my dream I swam with dolphins. I was overtaken by a wave that surprised me, rolling up from behind. It was too big, and I was too late to jump over it. So I was pulled down. Underwater, I collided with bricks and boulders and baby dolphins. Finally escaping the debris, bruised and battered, I floated, just dangling in the gray water while around me stars silently fell down. It was peaceful, so tempting to stay put. Was I prepared to die? I could not pretend this wasn’t happening. To me. Who was I now? I couldn’t remember. Did anyone need me anymore? No, the dolphins were gone. So I could go. I could rise above the bricks and leave the darkness behind. Wake up. Up and up. I could brave the wildest waves all the way home.

What have I done, I thought the next morning, upon awakening, when I couldn’t get up from the bed I’d sprung out of so many mornings to get to the hospital so Marika wouldn’t wake up alone. There was nothing to get up for. For the first time in my life I didn’t want to get up. I wanted to die.

Duetting: Memoir 58

Warning: The following is an account of witnessing my daughter’s last breaths. A beautiful but very sad memory, it was important to me to include it here. But if you do not want to be faced with intense sadness you might want to simply enjoy my illustration and forego the reading this week.

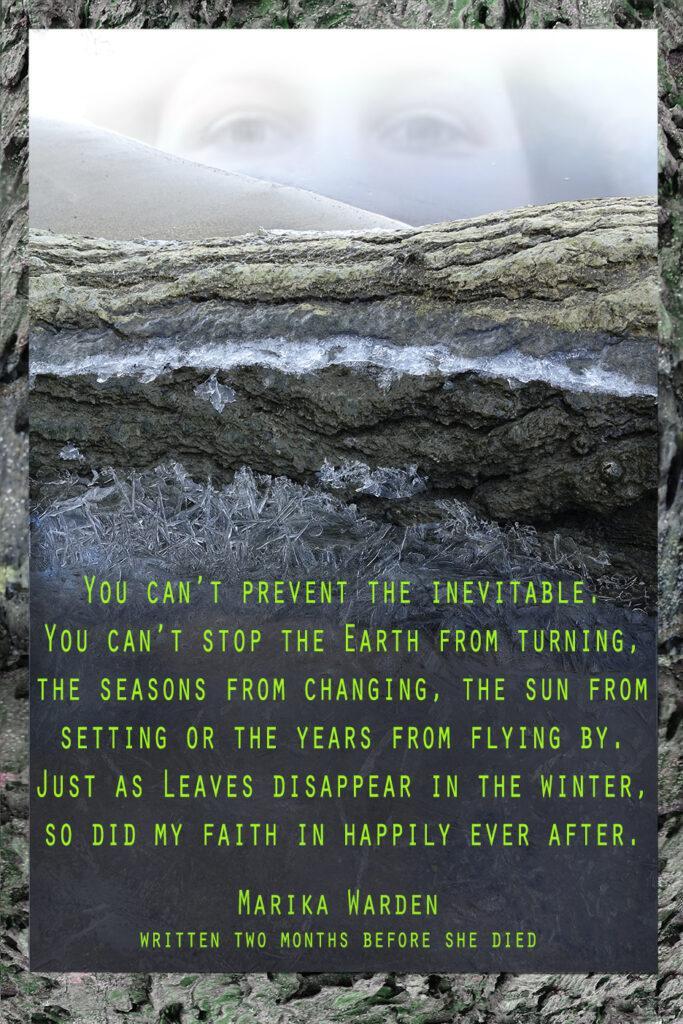

As a mother preparing for my daughter’s impending death, I needed to see the beautiful life I’d brought into the world carefully wrapped up and tucked in snuggly. This was really happening. There was no stopping it, no stopping time. It was past the time for hope.

Marika’s father and I had promised her peace, that we wouldn’t fight. We had worked hard to hold things together. But on Friday, March 4, 2011, the day we were to let her go, we were both on the dark, uneven edges of our individual cliffs. We’d agreed to “have it happen” at one o’clock. But suddenly, in the middle of the morning, her father announced he couldn’t stand it any longer; it had to happen right then. His wife couldn’t bear to watch him suffer. So there we were. The time that had been ticking away was suddenly taken away.

The nurses asked us to leave. We would be called back soon to be with her for the end. Marika’s father, his wife, my son, and my friend Celia slipped quietly out the glass door. I did not. The preparations for disengagement of life support would not be pretty. But I wanted to be there anyway. I held onto Marika’s feet, and looked the nurses straight in the eyes through a blur of tears.

“I’ve been with her through everything else,” I said, trying to collect myself in between gasps, “I want to stay.” And they invited me to come closer to where Marika lay in the milky light of the overhead fixture that hummed on center stage. There, the nurses, like Disney bluebirds attending Sleeping Beauty, flitted about undressing ribbons of tubing, tying up cords, primping and preening her. They fidgeted with the monitors. Marika looked peaceful and trusting.

Are you dreaming, Mareek? I said to her, in my head. My Hurricane Marika, where’s your thunder now? You know you could tear out these lines and rip apart these bags of blood and drugs. You could throw the IV stands javelin-style through the glass walls and make torrential waves shatter and smash everything. You’re still alive.

I wrapped my hand around her forearm. The nurses checked her eyes one more time, shining a small flashlight under her lids. She had the warmest hazel eyes. It’s okay, Mareek.

It wasn’t okay. I hated hearing myself say those words. That was something I said when she didn’t win her soccer game or didn’t get the grade she’d expected on a school project. ‘It’s okay’ meant she’d get over it and things would work out better next time.

They unhooked the bags of meds draped up and down the twin IV stands, leaving only the painkillers. I watched Marika’s perfectly arched eyebrows for signs of discomfort as they swabbed and then suctioned her mouth. The monitors ticked. After weeks of constantly checking their displays, I couldn’t stop peeking at the blinking green digits.

There was no plug to pull. There was no lethal injection. It was simply a matter of removing the air that was being pumped in. First the nurses peeled the tape from her face and gently wiped the tape marks from her chin and cheeks. Then they pulled out the breathing tube that delivered air, and stuck another tube deep into her mouth to suction out her throat once more. I heard the air hissing and then sucking. The monotonous hum, ticking, and beeps of the monitors comforted me; they meant she was still here. The air tube was gone now and she breathed on her own. I inhaled and exhaled every breath with her. Keep breathing, Mareek. Breathe. Breathe.

The others filed back in around us. Her father found the monitors too distracting, so a nurse turned them off. The screens that exhibited Marika’s life in glowing green turned dark. I felt for her pulse the way I learned as a lifeguard. Still strong.

You’re still breathing. Marika breathed seconds long enough for me to imagine her never stopping, long enough to imagine a chorus of nurses singing “mistake” and “miracle.”

How long can you keep breathing? Sweet breaths. Shallow breaths. She would not last long now.

You’re still here. I’m here. I need to focus, wake up. Watch. The now I know will be different on the other side of a blink.

Her mouth opened and took in no air this time. It closed and opened and hesitated. Her lips gently shut and opened and shut. And opened. Gently. Slowly.

Rest, Mareek. My Mareek, it’s okay. Her mouth was suspended open.

Rest. I love you. I had only her pulse. Pulse, no breathing. She was really going.

You are so beautiful. Pulse slowed.

Here. Still here. She was still here.

Here. Still.

Here.

Still.

Gone?

All gone?

Gone.

The clock said 12:28. I wanted the nurses to notice. It was 12:28 and Marika was gone.

I held her hand and stared: Lavender lined eyelids. Rosebud lips. The tiny spot that had been on her left chin forever. And I kept checking in with the clock, watching time fall away. March 4, 2011, 12:28 pm vanished. Just dropped off the planet. Overtaken by 12:29, and then 12:30. Wishing the whole world would end, I watched as the part of me that could sing and fly disappeared into nowhere. I waited. Like time might suddenly rewind. But wherever Marika was, her body was empty. She’d abandoned it. Some essence, some energy, was no longer there. This was not her. This was just her house. Her beautiful house with its scuffed walls and once-bright windows through which once emanated sweet songs. And sometimes thunder.

I hope there was light, Mareek. I hope you saw light.

Please, whoever or whatever you are out there—God? —please don’t deprive her of the light.

Duetting: Memoir 57

Mareek, I want to tell you the story of your birth, I rambled on in my head as I rubbed my dying daughter’s feet. I could not remember if I’d ever told Marika that story. This was on the third day of March 2011, shortly after I’d signed the papers to end her life. Consumed by the unfairness and all she would be losing out on, I was feeling like the worst kind of thief. I could not yet imagine my own loss, how that would feel. I’d failed her. I couldn’t tell my mother or even Laurie. There was only one day left to get close enough to death to accept it, to learn to love it. So, standing at the foot of her bed, I brought up the memory of when she was born, and then I tried to convince myself of everything I’d ever heard about death: Death means freedom from pain. Death is a transition, not an end. Our dying begins the moment we take our first breath so death is simply the last part of life.

Many rave about watching a birth, welcoming oncoming life that blooms from womb to world. And your birth, Mareek, was one of my most magnificent moments. But really, witnessing the exiting of life, even when walloped by sorrow, is awe-inspiring. Life, when it enters the world can be traced back to the source of the seed. But its departing is shrouded in mystery. A year and a half earlier, I had tried to watch as life evaporated from the still form of my father into nowhere. I stared, transfixed on an invisible drama, detecting only the signs of a soul having already taken flight: his just-stopped pulse and empty lifeless eyes. My father’s eyes were half open, dark black marbles that caught glints of light, even at the end. I wondered, for how long could he still see me as his mouth opened and closed, opened and closed so slightly like a dazed fish out of water gently gasping for breath? He seemed unaware he was not catching any air towards the end. He lay there calm and still while his family shook in sobs. I watched, but could not tell if the life ebbed out of him slowly or if it left as in the flick of a switch.

Where life goes in the time it takes for a heart to stop beating is an astounding mystery. Is the life locked dormant inside or does it dissipate into the negative space between those grieving? Does it escape into countless particles of dust? Are there a gazillion invisible, homeless souls freed from their earthly shells, crammed around us, hovering over the ones they loved and left behind, hoping to be reborn?

Mareek, I’d named you Marika Joy before you were even conceived. Yes, I knew you were out there waiting for me somewhere. Like the crocuses that herald in the spring. I always knew I would have a daughter one day. And I’d love the warmth of your dark-haired head on my cheek. ‘Marika’ was the most beautiful, magical name I’d ever heard. You were named after a flower, a Twelve Apostles Neo-Marica. A walking iris. And Joy, for your paternal grandmother, a precious life snuffed out too soon by cancer. A spark of her would live on, be reborn with you. Yeah. Too bad we couldn’t have erased the cancer genes from those sparks of Grandma Joy’s.

You were late, Mareek. You were supposed to arrive in April, the month of your father’s and my birthdays. You were taking your time but Doctor Kyong wanted to go on his vacation. So he had me choose a day in May from three convenient dates. I was embarrassed by this as all my pregnant friends were having natural childbirth with no interventions, no drugs. Back then childbearing was like being in some sort of Amazon birthing marathon, but being ten years older than everyone else, I had to comply with a different set of rules, or lose my adored doctor.

I chose May third. Three letters each in May and Joy. And so, early in the morning on May 3, 1990, your father and I arrived at the hospital after leaving friends in charge of your brother, our businesses, and the pets. The nurses gave me some drug, oxytocin, to induce my labor. And then an enema. But there was no progress in my dilating. We waited. And walked and waited. Wearing the special kimono-style birthing robe I’d sewn from fabric with joyful bursts of blossoms, we walked the halls of the hospital and waited all day. You were already finding ways to defy demands and doctors. There was little that was natural or unplanned except you simply were not ready, were not complying with anyone else’s agenda but your own.

I don’t remember pushing, Mareek. I don’t remember pain. I remember waiting, maybe a little impatiently, to see your face and be on our way to our great adventure together. My water was broken for me in the afternoon and then there were fierce contractions. I growled like a wild animal and hugged your father hard. They injected me with three paracervical blocks for pain relief, and finally, just at dinnertime, supported by your father, I squatted, extending one leg out like a Russian dancer. After some grunting I was cut open to make it easier for you. Then I ripped open even more. Suddenly there was a great avalanche inside me. And you tumbled out, surprised, kicking and demanding, What’s for dinner, Mom? You chomped down eagerly, nursing right away as they stitched me back up. You were purple and bruised. You were perfect. I loved you immediately. My Marika Joy. A true Taurus, my friends said. Everyone expected you to be solid and steady and strong. And stubborn. And you were.